1. SLVIA Methodology

1.1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction

- This appendix of the Offshore Environmental Impact Assessment Report (EIA Report) presents the methodology used within the seascape, landscape and visual impact assessment (SLVIA) of the potential impacts of the Berwick Bank Wind Farm offshore infrastructure (hereafter referred to as “the Proposed Development”) on seascape, landscape and visual receptors.

- Specifically, this SLVIA chapter considers the potential impact of the Proposed Development seaward of Mean High Water Springs (MHWS) during the construction, operational and maintenance, and decommissioning phases. This chapter also considers the impact of offshore infrastructure on onshore receptors (landward of MHWS) within the SLVIA study area (Figure 15.2) during the construction, operational and maintenance, and decommissioning phases.

- The Proposed Development Array Area is located 37.8 km east of the Scottish Borders coastline (St Abb’s Head) at its closest point and located within the former Firth of Forth Zone (Figure 15.1). The Proposed Development Array Area comprises an area of approximately 1,010 km2 overlapping the large-scale morphological banks ‘Marr Bank’ and ‘Berwick Bank’. The maximum design scenario for the SLVIA comprises 179 offshore WTGs at a maximum blade tip height of 355 m and a maximum rotor diameter of 310 m.

- This SLVIA methodology appendix is structured as follows:

- overview of SLVIA methodology;

- iterative assessment and design;

- guidance, data sources and site surveys;

- assessing visual effects;

- assessing night-time visual effects;

- assessing seascape/landscape effects;

- evaluation of significance;

- nature of effects;

- assessing cumulative seascape, landscape and visual effects; and

- visual representations.

1.2. Overview of SLVIA Methodology

1.2. Overview of SLVIA Methodology

1.2.1. Introduction

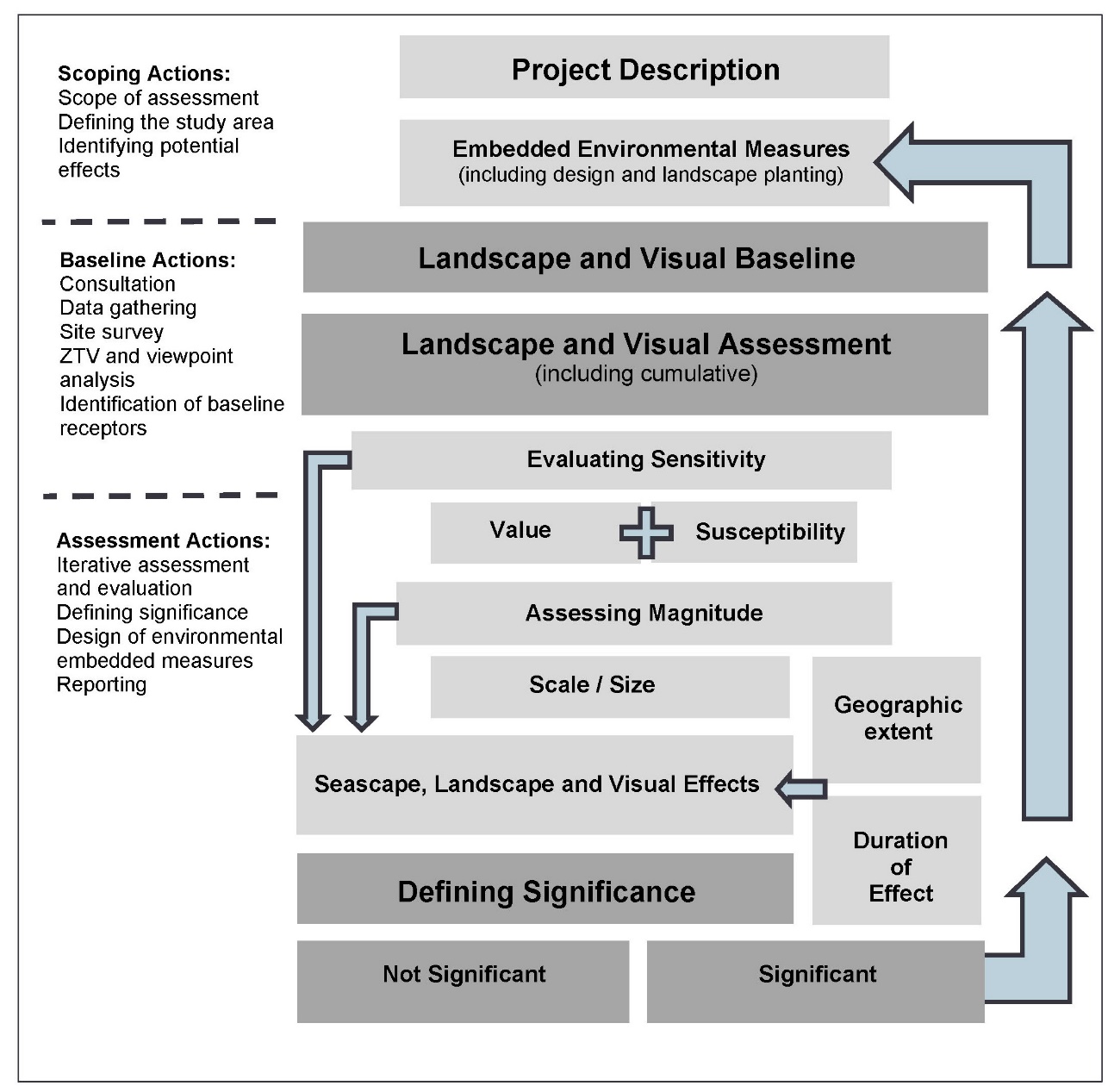

- The assessment has been undertaken in accordance with the Landscape Institute and IEMA (2013) Guidelines for Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment, 3rd Edition (GLVIA3), and other best practice guidance. An overview or summary of the SLVIA process is provided here and illustrated, diagrammatically in Table 1.1.

- The SLVIA assesses the likely effects that the construction and operation of the Proposed Development on the seascape, landscape and visual resource, encompassing effects on seascape/landscape character, designated landscapes, visual effects and cumulative effects.

- The SLVIA is based on the Rochdale Envelope described in as described in Chapter 3: Project Description. In compliance with EIA regulations, the likely significant effects of a realistic ‘worst case’ scenario are assessed and illustrated in the SLVIA. This worst-case scenario is described in Chapter 15: Seascape, landscape and visual.

- The evaluation of sensitivity takes account of the value and susceptibility of the receptor to the Proposed Development. This is combined with an assessment of the magnitude of change which takes account of the size and scale of the proposed change. By combining assessments of sensitivity and magnitude of change, a level of seascape, landscape or visual effect can be evaluated and determined. The resulting level of effect is described in terms of whether it is significant or not significant, and the geographical extent, duration and the type of effect is described as either direct or indirect; temporary or permanent (reversible); cumulative; and beneficial, neutral or adverse.

Table 1.1: Overview of Approach to the SLVIA

- The assessment has also considered the cumulative effects likely to result from additional changes to the seascape, landscape and visual amenity caused by the Proposed Development in conjunction with other developments that occurred in the past, present or are likely to occur in the foreseeable future.

- In each case an appropriate and proportionate level of assessment has been undertaken and agreed through consultation at the scoping stage. The level of assessment may be ‘preliminary’ (requiring desk-based data analysis) or ‘detailed’ (requiring site surveys and investigations in addition to desk-based analysis).

- The seascape, landscape and visual assessment unavoidably, involves a combination of quantitative and qualitative assessment and wherever possible a consensus of professional opinion has been sought through consultation, internal peer review, and the adoption of a systematic, impartial, and professional approach.

1.2.2. Defining the Study Area

- The Proposed Development Array Area is located offshore in the Outer Forth and Firth of Tay area of the North Sea, approximately 37.8 km from the closest section of coastline at St. Abbs Head in the Scottish Borders, 44.8 km from the East Lothian coastline (Torness Point), 40.3km from the Angus coastline (Prail Castle) and 40.9 km from the Fife coastline (Fife Ness).

- The SLVIA study area for the Proposed Development is proposed as covering a radius of 60 km from the Proposed Development Array Area, as illustrated in Figure 15.2

- Broadly, the SLVIA study area is defined by a large area of the seascape including parts of the Forth and Tay Estuaries and includes the coastal areas of Aberdeenshire, Angus, Fife, East Lothian, Scottish Borders and Northumberland.

- The SLVIA will generally focus on locations from where it may be possible to see the Proposed Development, as defined by the blade tip Zone of Theoretical Visibility (ZTV), which is presented in Figure 15.5 (A3 scale).

- Consideration of the blade tip ZTV indicates that theoretical visibility of the Proposed Development mainly occurs within 60 km and that beyond this distance, the geographic extent of visibility will become very restricted. At distances over 60 km, the lateral (or horizontal) spread of the Proposed Development will also occupy a small portion of available views and the apparent height (or ‘vertical angle’) of the wind turbines would also appear very small, therefore significant visual effects are unlikely to arise at greater than this distance, even if the wind turbines are theoretically visible.

- The influence of earth curvature begins to limit the apparent height and visual influence of the wind turbines visible at long distances (such as over 60 km), as the lower parts of the turbines would be partially hidden behind the apparent horizon, leaving only the upper parts visible above the skyline.

- The SLVIA study area is defined as the outer limit of the area where significant effects could occur, using professional judgement. Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment Guidance (IEMA, 2015 and 2017) recommends a proportionate EIA focused on the significant effects. An overly large SLVIA study area may be considered disproportionate if it makes the understanding of the key impacts of the Proposed Development more difficult.

- This is supported by Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment (LVIA) Guidance produced by the Landscape Institute (GLVIA3) (Landscape Institute, 2013) (para 3.16). This guidance recommends that:

‘The level of detail provided should be that which is reasonably required to assess the likely significant effects’. Para 5.2 and p70 also states that ‘The study area should include the site itself and the full extent of the wider landscape around it which the Proposed Development may influence in a significant manner’.

- Other wind farm specific guidance, such as NatureScot’s Visual Representation of Wind Farms Guidance (NatureScot, 2017) recommends that ZTV distances are used for defining study area based on wind turbine height. This guidance recommends a 45 km radius for wind turbine greater than 150 m to blade tip (para 48, p12), however it does not go beyond turbines above 150 m in height. The height of current offshore wind turbine models has now exceeded the heights covered in this guidance. The NatureScot guidance recognises that greater distances may need to be considered for larger wind turbines used offshore, as is the case for the SLVIA study area for the Proposed Development.

- Other projects in the SLVIA study area, such as Inch Cape and Seagreen 1, defined a 50 km radius study area for the purposes of their SLVIA. A precautionary approach is taken in defining a 60 km radius study area for the Proposed Development due to the larger proposed maximum blade tip height of 355 m above LAT. Potential cumulative effect interactions with these other offshore wind farms (OWFs) have also influenced the definition of the SLVIA study area. Other offshore windfarms within the SLVIA study area are shown in Figure 15.16

- The variation of weather conditions influencing visibility off the coast has also informed the SLVIA study area. Based on understanding of Met Office data, visibility beyond 60 km is likely to be very infrequent.

- In considering the SLVIA study area, the sensitivity of the receiving seascape, landscape and visual receptors has also been reviewed, taking particular account of the landscape designations shown in Figure 15.4 and other visual receptors. These include the nationally designated Northumberland Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), which is located approximately 47.9 km from the Proposed Development Array Area.

- Seascape, landscape and visual effects as a result of the Proposed Development are proposed to be scoped out beyond 60 km. The study area will be reviewed and amended in response to such matters as refinement of the Proposed Development, the identification of additional impact pathways and in response, where appropriate, to feedback from consultation.

1.2.3. Wind Energy Baseline

- In accordance with NatureScot guidance and GLVIA3 (para 7.13), existing projects and those which are under construction (Chapter 15, Table 15.42) are included in the SLVIA baseline and described as part of the baseline conditions, including the extent to which these have altered character and views, and affected sensitivity to windfarm development. An assessment of the additional effect of the Proposed Development is undertaken in conjunction with a baseline that includes operational and under-construction projects as part of the main assessment in Chapter 15, Section 15.11.

- Neart na Gaoithe offshore wind farm is under construction offshore as of August 2020 and is expected to be operational in 2023. SeaGreen 1 offshore wind farm (SeaGreen 1) is under construction offshore as of December 2020 and is also expected to be operational in 2023. As they are both currently under-construction and expected to be operational before the Proposed Development starts construction offshore, in accordance with GLVIA3, both Neart na Gaoithe and SeaGreen 1 are assumed to be part of the baseline i.e., they are assumed to be operational for the purposes of the SLVIA.

- The baseline photographs shown in Figures 15.21 – 15.48 (Appendix 15.2) were taken prior to the completion of construction of Neart na Gaoithe and SeaGreen 1, therefore the Neart na Gaoithe and SeaGreen 1 wind turbines and their aviation lights have been added (i.e. photomontaged) into the baseline photographs to visually represent their appearance as part of the baseline. The theoretical extent of visibility of Neart na Gaoithe and SeaGreen 1 in the baseline is shown in the ZTVs in Figure 15.17 and Figure 15.18

1.3. Iterative assessment and design

1.3. Iterative assessment and design

- The SLVIA is part of an iterative EIA process which aims to ‘design out’ significant effects via a range of environmental measures including avoidance and design that aim to reduce or eliminate significant effects. Design is an integrated part of the SLVIA process and environmental measures related to landscape design and management can be an important tool to mitigate significant effects. The EIA process can also call on a range of environmental and technical specialists that contribute other forms of mitigation that may also bring a range of benefits. Potentially significant seascape, landscape and visual effects and the constraints and opportunities connected with their resolution are identified through the SLVIA process. Where possible embedded environmental measures are incorporated into the Proposed Development in order to mitigate potential seascape, landscape and visual effects, which are identified as follows.

1.3.1. Potential effects during construction and decommissioning

- Potential effects on the seascape, landscape and visual resource may occur during the construction and decommissioning phases of the Proposed Development, including:

- Seascape effects:

– Effects on perceived seascape character, arising as a result of the construction and decommissioning activities (including laying new offshore export cables to shore) and structures located within the array area, which may alter the seascape character of the array area itself and the perceived character of the wider seascape through visibility of these changes.

- Landscape effects:

– Effects on perceived landscape character, arising as a result of the construction and decommissioning activities and structures, including laying new offshore export cables to shore, which will be visible from the coast and may therefore affect the perceived character of the landscape.

– Effects on the special landscape qualities and integrity of designated landscapes as a result of the above construction and decommissioning activities.

- Visual effects:

– Effects on views and visual amenity experienced by people from principal visual receptors and representative viewpoints, arising as a result of the construction and decommissioning activities and structures, including laying new offshore export cables to shore, which will be visible from the coast.

- Whole Proposed Development effects:

– Whole Proposed Development effects could occur as a result of multiple construction and decommissioning activities related to the onshore and/or the offshore elements of the Project affecting a seascape, landscape or visual receptor. Effects will be influenced by the construction phasing of the offshore and offshore elements of the Project, the geographic location of receptors an visibility of the onshore and offshore elements.

1.3.2. Potential effects during operation and maintenance

- Potential effects on the seascape, landscape and visual resource may occur during the operation and maintenance of the Proposed Development over its operational lifetime, including:

- Seascape effects:

– Effects on perceived seascape character (SCAs), arising as a result of the operational WTGs, substations and maintenance activities located within the array area, which may alter the seascape character of the array area itself and the perceived character of the wider seascape.

- Landscape effects:

– Effects on perceived landscape character (LCAs and Designations), arising as a result of the operational WTGs, substations and maintenance activities, which will be visible from the coast and may therefore affect the perceived character of the landscape. Effects on defined special qualities of designated landscapes.

- Visual effects:

– Effects on views and visual amenity experienced by people as principal visual receptors and representative viewpoints, arising as a result of the operational WTGs, substations and maintenance activities, marine navigation and aviation lighting.

- Cumulative effects:

– Effects of operation of the Proposed Development that have the potential to contribute to cumulative seascape, landscape and visual effects including effects on seascape, landscape and visual amenity due to inter-visibility with other planned developments.

1.4. Guidance, data sources and site surveys

1.4. Guidance, data sources and site surveys

1.4.1. Guidance on methodology

- This assessment has been carried out in accordance with the principles contained within the following documents:

- Landscape Institute and IEMA (2013) - Guidelines for Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment: Third Edition (GLVIA3).

- Landscape Institute (2019). Visual Representation of Development Proposals.

- NatureScot (2012). Assessing the Cumulative Impact of Onshore Wind Energy Developments.

- NatureScot (2012). Offshore Renewables – Guidance on Assessing the Impact on Coastal Landscape and Seascape. Guidance for Scoping an Environmental Statement.

- NatureScot (2017). Visual Representation of Wind farms, Guidance (Version 2.2).

- NatureScot (2018). Guidance Note. Coastal Character Assessment (Version 1a).

- This methodology accords with GLVIA3. Where it diverges from specific aspects of the guidance, in a small number of areas, reasoned professional justification for this is provided as follows.

- GLVIA3 sets out an approach to the assessment of magnitude of change in which three separate considerations are combined within the magnitude of change rating. These are the size or scale of the effect, its geographical extent and its duration and reversibility. This approach is to be applied in respect of both landscape and visual receptors. It is considered that the process of combining all three considerations in one rating can distort the aim of identifying significant effects of wind farm development. For example, a high magnitude of change, based on size or scale, may be reduced to a lower rating if it occurred in a localised geographical area and for a short duration. This might mean that a potentially significant effect could be overlooked if effects are diluted down due to their limited geographical extents and/ or duration or reversibility.

- The consideration of the size or scale of the effect, its geographical extent and its duration and reversibility are kept separate, by basing the magnitude of change primarily on size or scale to determine where significant and non-significant effects occur, and then describing the geographical extents of these effects and their duration and reversibility separately. Duration and reversibility are stated separately in relation to the assessed effects (i.e. as short/medium/long-term and temporary/permanent) and are considered as part of drawing together conclusions about significance and combining with other judgements on sensitivity and magnitude, to allow a final judgement to be made on whether each effect is significant or not significant.

- OPEN’s assessment methodology utilises six word scales of magnitude of change – high, medium-high, medium, medium-low, low and negligible; which are preferred to the ‘maximum of five categories’ suggested in GLVIA3 (3.27), as a means of clearly defining and summarising magnitude of change judgements.

- These are not new diversions and follow practice established on other large scale offshore wind farm projects such as Moray East, East Anglia TWO, Norfolk Vanguard and Thanet Extension.

1.4.2. Data sources

- The data sources that have been collected and used to inform this SLVIA are summarised in Table 1.2 Open ▸ .

Table 1.2: Data Sources used to inform the SLVIA

1.4.3. Appropriate level of assessment

- The SLVIA methodology provides for an approach to identifying receptors that could be significantly affected by the Proposed Development that need to be ‘scoped in’ for further assessment in the SLVIA and receptors that could not be significantly affected and that can be ‘scoped out’ of the assessment.

- The general principle is that receptors that could be significantly affected will be identified based on their sensitivity/importance/value and the spatial and temporal scope of the assessment. Consultation has also informed the selection of potential receptors that could be significantly affected by the Proposed Development.

- The assessment of whether an effect has the potential to be of likely significance has been based upon review of existing evidence base, consideration of commitments made (embedded environmental measures), professional judgement and where relevant, recommended aspect specific methodologies and established practice. In applying this judgement, use has been made of a simple test that to be significant an effect must be of sufficient importance that it should be taken into consideration when making a development consent decision.

- For those matters ‘scoped in’ for assessment, the approach to level of assessment is tiered. A ‘preliminary’ or ‘detailed’ assessment is undertaken as follows:

- a ‘preliminary assessment’ approach for an environmental aspect/effect which may include secondary baseline data collection (for example desk-based information) and qualitative assessment methodologies. A preliminary assessment of all seascape, landscape and visual receptors within the ZTV is undertaken in Chapter 15, using desk-based information and ZTV analysis (Figure 15.9 – 15.12). The preliminary assessment identifies which seascape, landscape and visual receptors are unlikely to be significantly affected, which are subject to a preliminary assessment, and those receptors that are more likely to be significantly affected by the Proposed Development which require a ‘detailed assessment’; and

- a ‘detailed assessment’ approach is undertaken for seascape, landscape and visual receptors/effects that are identified in the preliminary assessment as requiring detailed assessment. This detailed assessment may include primary baseline data collection (for example through site surveys), quantitative and qualitative assessment methodologies, and modelling such as ZTV analysis (Figure 15.9 – 15.12) and wireline/photomontage visualisations (Figure 15.21 – 15.48).

- To ensure the provision of a proportionate EIA and an ES that is focused on likely significant effects, the assessment takes into account the considerable levels of existing environmental information available, extensive local geographical knowledge and understanding of the site and surroundings gained from ongoing site selection analysis and environmental surveys. The spatial and temporal scope of the assessment enables the identification of receptors which may experience a change as a result of the Proposed Development.

1.4.4. Desk-based and site survey work

- The SLVIA undertaken as part of the ES has been informed by desk-based studies, stakeholder consultations and field survey work undertaken within the SLVIA Study Area. The landscape, seascape and visual baseline has been informed by desk-based review of landscape and seascape character assessments, and the ZTV, to identify receptors that may be affected by the Proposed Development and produce written descriptions of their key characteristics and value.

- Interactions have been identified between the Proposed Development and seascape, landscape and visual receptors, to predict potentially significant effects arising and measures are proposed to mitigate effects.

- For those receptors where a detailed assessment is required, primary data acquisition has been undertaken through a series of surveys. These surveys include field survey verification of the ZTV from terrestrial landscape character areas (LCAs), micro-siting of viewpoint locations, panoramic baseline photography and visual assessment survey from all representative viewpoints. These surveys were undertaken between October 2021 and January 2022 as described in Table 1.3 Open ▸ . Field work over the duration of the assessment has been partly restricted due to the travel restrictions in place during the COVID-19 pandemic, including requirements for assessors to ‘stay local/at home’ during certain periods, restricted access to certain visitor locations due to closures and limited accommodation availability.

Table 1.3: Site Surveys Undertaken

1.5. Assessing visual effects

- Visual effects are concerned wholly with the effect of the Proposed Development on views, and the general visual amenity and are defined by the Landscape Institute in GLVIA 3, paragraphs 6.1 as follows: “An assessment of visual effects deals with the effects of change and development on views available to people and their visual amenity. The concern ... is with assessing how the surroundings of individuals or groups of people may be specifically affected by changes in the context and character of views.”

- Visual effects are identified for different receptors (people) who will experience the view at their place of residence, within their community, during recreational activities, at work, or when travelling through the area. Visual effects may include changes to an existing static view, sequential views, or wider visual amenity as a result of development or the loss of particular landscape elements or features already present in the view.

- The level of visual effect (and whether this is significant) is determined through consideration of the sensitivity of each visual receptor (or range of sensitivities for receptor groups) and the magnitude of change that will be brought about by the construction, operation and decommissioning of the Proposed Development.

1.5.1. Zone of Theoretical Visibility (ZTV)

- Plans mapping the Zone of Theoretical Visibility (ZTV) are used to analyse the extent of theoretical visibility of the Proposed Development, across the Study Area and to assist with viewpoint selection. The ZTV does not however, take account of the screening effects of buildings, localised landform and vegetation, unless specifically noted (see individual figures). As a result, there may be roads, tracks and footpaths within the study area which, although shown as falling within the ZTV, are screened or filtered by built form and vegetation, which will otherwise preclude visibility. The ZTV provides a starting point in the assessment process and accordingly tend towards giving a ‘worst case’ or greatest calculation of the theoretical visibility.

1.5.2. Viewpoint analysis

- Viewpoint analysis is used to assist the assessment and is conducted from selected viewpoints within the Study Area. The purpose of this is to assess both the level of visual effect for particular receptors and to help guide the design process and focus the assessment. A range of viewpoints are examined in detail and analysed to determine whether a significant visual effect will occur. By arranging the viewpoints in order of distance it is possible to define a threshold or outer geographical limit, beyond which significant effects will be unlikely.

- The assessment involves visiting the viewpoint location and viewing wirelines and photomontages prepared for each viewpoint location. The fieldwork is conducted in periods of fine weather with good visibility and considers seasonal changes such as reduced leaf cover.

- The SLVIA therefore includes viewpoint analysis prepared for each viewpoint and presented as supporting assessment in the SLVIA. The viewpoint analysis assists in defining the direction, elevation, geographical spread and nature of the potential visual effects and identify areas where significant effects are likely to occur. This approach seeks to provide clarity and confidence to consultees and decision makers by allowing the detailed judgements on the magnitude of visual change to be more readily scrutinised and understood. The viewpoint analysis is used to assist the visual assessment of visual receptors reported in the SLVIA.

1.5.3. Evaluating visual sensitivity to change

- In accordance with paragraphs 6.31-6.37 of GLVIA3, the sensitivity of visual receptors has been determined by a combination of the value of the view and the susceptibility of the visual receptors to the change likely to result from the Proposed Development on the view and visual amenity.

Value of the view

- The value of a view or series of views reflects the recognition and the importance attached either formally through identification on mapping or being subject to planning designations, or informally through the value which society attaches to the view(s). The value of a view has been classified as high, medium-high, medium, medium-low or low and the basis for this assessment has been made clear using evidence and professional judgement, based on the following criteria.

- Formal recognition - The value of views can be formally recognised through their identification on OS or tourist maps as formal viewpoints, sign-posted and with facilities provided to add to the enjoyment of the viewpoint such as parking, seating and interpretation boards. Specific views may be afforded protection in local planning policy and recognised as valued views. Specific views can also be cited as being of importance in relation to landscape or heritage planning designations, for example the value of a view has been increased if it presents an important vista from a designed landscape or lies within or overlooks a designated area, which implies a greater value to the visible landscape.

- Informal recognition - Views that are well-known at a local level and/or have particular scenic qualities can have an increased value, even if there is no formal recognition or designation. Views or viewpoints are sometimes informally recognised through references in art or literature and this can also add to their value. A viewpoint that is visited or appreciated by a large number of people will generally have greater importance than one gained by very few people.

Susceptibility to change

- Susceptibility relates to the nature of the viewer experiencing the view and how susceptible they are to the potential effects of the Proposed Development. A judgement to determine the level of susceptibility therefore relates to the nature of the viewer and their experience from that particular viewpoint or series of viewpoints, classified as high, medium-high, medium, medium-low or low and based on the following criteria.

- Nature of the viewer - The nature of the viewer is defined by the occupation or activity of the viewer at the viewpoint or series of viewpoints. The most common groups of viewers considered in the visual assessment include residents, motorists, and people taking part in recreational activity or working. Viewers, whose attention is focused on the landscape, or with static long-term views, are likely to have a higher sensitivity. Viewers travelling in cars or on trains will tend to have a lower sensitivity as their view is transient and moving. The least sensitive viewers are usually people at their place of work as they are generally less sensitive to changes in views.

- Experience of the viewer - The experience of the visual receptor relates to the extent to which the viewer’s attention or interest may be focused on the view and the visual amenity they experience at a particular location. The susceptibility of the viewer to change arising from the offshore elements of the Proposed Development may be influenced by the viewer’s attention or interest in the view, which may be focused in a particular direction, from a static or transitory position, over a long or short duration, and with high or low clarity. For example, if the principal outlook from a settlement is aligned directly towards the offshore elements of the Proposed Development, the experience of the visual receptor will be altered more notably than if the experience relates to a glimpsed view seen at an oblique angle from a car travelling at speed. The visual amenity experienced by the viewer varies depending on the presence and relationship of visible elements, features or patterns experienced in the view and the degree to which the landscape in the view may accommodate the influence of the offshore elements of the Proposed Development.

Visual sensitivity rating

- An overall level of sensitivity has been applied for each visual receptor or view – high, medium-high, medium, medium-low or low – by combining individual assessments of the value of the view and the susceptibility of the visual receptor to change. Each visual receptor, meaning the particular person or group of people likely to be affected at a specific viewpoint, is assessed in terms of their sensitivity. The basis for the assessments has been made clear using evidence and professional judgement in the evaluation of each receptor. Criteria that tend towards higher or lower sensitivity are set out in Table 1.4 Open ▸ below.

Table 1.4: Visual Sensitivity to Change Criteria

1.5.4. Visual magnitude of change

- The magnitude of change on views is an expression of the scale of the change that will result from the Proposed Development and is dependent on a number of variables regarding the size or scale of the change. The consideration of the size or scale of the effect, its geographical extent and its duration and reversibility are kept separate, by basing the magnitude of change primarily on size or scale to determine where significant and non-significant effects occur, and then describing the geographical extents of these effects and their duration and reversibility separately.

Size or scale of change

- An assessment has been made about the size or scale of change in the view that is likely to be experienced as a result of the Proposed Development, based on the following criteria:

- Distance: the distance between the visual receptor/viewpoint and the Proposed Development. Generally, the greater the distance, the lower the magnitude of change, as the Proposed Development will constitute a smaller scale component of the view.

- Size: the amount and size of the Proposed Development that will be seen. Visibility may range from small or partial visibility of the Proposed Development to all of the offshore elements being visible. Generally, the larger and greater number of the Proposed Development that appear in the view, the higher the magnitude of change. This is also related to the degree to which the Proposed Development may be wholly or partly screened by landform, vegetation (seasonal) and / or built form. Conversely open views are likely to reveal more of the Proposed Development, particularly where this is a key characteristic of the landscape.

- Scale: the scale of the change in the view, with respect to the loss or addition of features in the view and changes in its composition. The scale of the Proposed Development may appear larger or smaller relative to the scale of the receiving seascape/landscape.

- Field of view: the vertical / horizontal field of view (FoV) and the proportion of the view that is affected by the Proposed Development. Generally, the more of the proportion of a view that is affected, the higher the magnitude of change will be. If the Proposed Development extend across the whole of the open part of the outlook, the magnitude of change will generally be higher as the full view will be affected. Conversely, if the Proposed Development cover just a narrow part of an open, expansive and wide view, the magnitude of change is likely to be reduced as they will not affect the whole open part of the outlook. This can in part be described objectively by reference to the horizontal / vertical FoV affected, relative to the extent and proportion of the available view.

- Contrast: the character and context within which the Proposed Development will be seen and the degree of contrast or integration of any new features with existing landscape elements, in terms of scale, form, mass, line, height, colour, luminance and motion. Contrasts and changes may arise particularly as a result of the rotation movement of the WTG blades, as a characteristic that gives rise to effects. Developments which contrast or appear incongruous in terms of colour, scale and form are likely to be more visible and have a higher magnitude of change.

- Consistency of image: the consistency of image of the Proposed Development in relation to other developments. The magnitude of change of Proposed Development is likely to be lower if its WTG height, arrangement, and layout design are broadly similar to other developments in the seascape, in terms of its scale, form and general appearance. New development is more likely to appear as logical components of the landscape with a strong rationale for their location.

- Skyline/background: Whether the Proposed Development will be viewed against the skyline or a background seascape may affect the level of contrast and magnitude. If the Proposed Development add to an already developed skyline the magnitude of change will tend to be lower.

- Number: generally, the greater the number of separate Proposed Development seen simultaneously or sequentially, the higher the magnitude of change. Further effects will occur in the case of separate developments and their spatial relationship to each other will affect the magnitude of change. For example, development that appears as an extension to an existing development will tend to result in a lower magnitude of change than a separate, new development.

- Nature of visibility: the nature of visibility is a further factor for consideration. The Proposed Development may be subject to various phases of development change and the way the Proposed Development may be viewed could be intermittent or continuous and / or seasonally, due to periodic management or leaf fall.

Geographical extent

- The geographic extent over which the visual effects will be experienced has also been assessed. This is distinct from the size or scale of effect and is described in terms of the physical area or location over which it will be experienced (described as a linear or area measurement). The extent of the effects will vary according to the specific nature of the Proposed Development and is principally assessed through ZTV, field survey and viewpoint analysis of the extent of visibility likely to be experienced by visual receptors. The geographical extent of visual effects is described as per the following examples.

- The geographical extent can be described as an area measurement or proportion of the total area of the receptor affected. For example, effects on people within a particular area such as a country park or area of common land can be illustrated via a ‘representative viewpoint’ that represents a similar visual effect, likely to be experienced by larger numbers of people within that area. The geographical extent of that visual effect can be expressed as approximately ‘5 hectares’ or ‘10%’ of an area of land or defined recreational area.

- The geographical extent can be described as a linear measurement (m or km) according to the length of route affected. For example, effects on people travelling on a route through the landscape such as a road or footpath can be illustrated via a ‘representative viewpoint’ that represents a similar visual effect, likely to be experienced by larger numbers of people along that route. The geographical extent of that visual effect can be expressed as approximately ‘2 km’ or ‘10%’ of the total length of the route.

- The geographical extent of a visual effect experienced from a specific viewpoint may be limited to that location alone, for example a public viewpoint recommended in tourist literature such as a well visited hill summit or a particular location within a built up or well vegetated area, where an uncharacteristically open or restricted view exists.

Duration and reversibility

- The duration and reversibility of visual effects are based on the period over which the Proposed Development are likely to exist (during construction and operation) and the extent to which the Proposed Development will be removed (during decommissioning), with effects reversed at the end of that period.

- Long-term, medium-term and short-term visual effects are defined as follows:

- long-term – more than 10 years (may be defined as permanent or reversible);

- medium-term – 6 to 10 years; and

- short-term – 1 to 5 years.

Visual magnitude of change rating

- The ‘magnitude’ or ‘degree of change’ resulting from the Proposed Development is described as ‘High’, ‘High-medium’, ‘Medium’, ‘Medium-low’ ‘Low’ and ‘Negligible’ as defined in Table 1.5 Open ▸ . The basis for the assessment of magnitude for each receptor has been made clear using evidence and professional judgement.

Table 1.5: Visual Magnitude of Change Ratings

- Examples of criteria that tend towards higher or lower magnitude of change that can occur on views and visual receptors are set out in Table 1.6 Open ▸ .

Table 1.6: Visual Magnitude of Change Criteria/Examples

1.5.5. Evaluating visual effects and significance

- The level of visual effect is evaluated through the combination of visual sensitivity and magnitude of change. Once the level of effect has been assessed, a judgement is then made as to whether the level of effect is ‘significant’ or ‘not significant’ as required by the relevant EIA Regulations. This process is assisted by the matrix in Table 1.10 Open ▸ which is used to guide the assessment. The factors considered in the evaluation of the sensitivity and the magnitude of the change resulting from the Proposed Development and their conclusion, have been presented in a comprehensive, clear and transparent manner.

- Further information is also provided about the nature of the effects (whether these will be direct/indirect; temporary/permanent/reversible; beneficial/neutral / adverse or cumulative).

- A significant effect is more likely to occur where a combination of the variables results in the Proposed Development having a defining effect on the view or visual amenity or where changes affect a visual receptor that is of high sensitivity.

- A non-significant effect is more likely to occur where a combination of the variables results in the Proposed development having a non-defining effect on the view or visual amenity or where changes affect a visual receptor that is of low sensitivity.

1.5.6. Visibility

- The varied clarity or otherwise of the atmosphere will reduce the number of days (the ‘frequency’) upon which views of the Proposed Development will be available from the coastline and hinterland, and is likely to inhibit clear views, rendering the WTGs located at long distance offshore, as visually recessive within the wider seascape. The effects of the construction and operation of the Proposed Development will vary according to the weather and prevailing visibility. This means that effects that are may be significant in the SLVIA under ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’ (i.e. worst-case/optimum) visibility conditions, may be not significant under moderate, poor or very poor visibility conditions.

- Assessments are based on a worst-case position of optimum (‘very good’ or ‘excellent’) visibility, in line with current guidance (Landscape Institute and IEMA, 2013), however within the visual assessment there is an assessment of the frequency or ‘likelihood’ of effect’ for each viewpoint, based on the distance of the Proposed Development, Met Office visibility data and professional judgement based on experience of viewing offshore wind farms in different conditions and distances. Likely visibility frequency can therefore been taken into consideration, with visibility range from viewpoints located at very long distances over 40km (where ‘excellent’ visibility is required) occurring less frequently than viewpoints at closer range.

- The photographs used in the photomontages shown in Figures 15.21 – 15.48 were captured between October 2021 to January 2022 in very good to excellent visibility conditions and show this maximum potential visibility of the Proposed Development. In reality the degree and extent of visual effects arising from the Proposed Development will be influenced by the prevailing weather and visibility conditions and such excellent visibility occurs relatively infrequently.

1.6. Assessing night-time visual effects

1.6. Assessing night-time visual effects

1.6.1. Introduction

- The assessment of night-time visual effects is based on the description of proposed WTG lighting set out in the project design envelope in Chapter 15 and the relevant ICAO/CAA regulations and standards, including Air Navigation Order 2016: Civil Aviation (CAA, 2016).

- The effect of the visible lights will be dependent on a range of factors, including the intensity of lights used, the clarity of atmospheric visibility and the degree of negative/positive vertical angle of view from the light to the receptor. In compliance with EIA regulations, the likely significant effects of a ‘worst-case’ scenario for WTG lighting are assessed and illustrated in this visual assessment.

- A worst-case approach is applied to the assessment that considers the potential effects of medium-intensity 2,000 candela (cd) aviation lights in clear visibility. It should be noted however, that medium intensity lights are only likely to be operated at their maximum 2,000 cd during periods of poor visibility. Photomontages showing 2,000 cd aviation lights are provided from representative viewpoints to support these worst-case assessments.

- It should be noted that the WTGs would also include infra-red lighting on the WTG hubs, which would not be visible to the human eye. Details of the lighting would be agreed with the MoD. The focus of the night-time visual assessment in this assessment is on the visible lighting requirements of the Proposed Development.

- The study area for the visual assessment of WTG lighting is shown in Figure 15.2 and is coincident with the 60 km SLVIA Study Area however, is particularly focused on the closest areas of the coastline.

- The assessment of the lighting of the Proposed Development is intended to determine the likely effects on the visual resource i.e. it is an assessment of the visual effects of aviation lighting on views experienced by people at night. The assessment of WTG lighting does not consider effects of aviation lighting on landscape or seascape character (i.e. landscape or seascape effects).

- ICAO indicates a requirement for no lighting to be switched on until ‘Night’ has been reached, as measured at 50 cd/m2 or darker. It does not require 2,000 candela medium intensity to be on during ‘twilight’, when landscape character may be discerned. The aviation and marine navigational lights may be seen for a short time during the twilight period when some recognition of landscape features/ profiles/ shapes and patterns may be possible. It is considered however, that level of recognition does not amount to an ability to appreciate in any detail landscape character differences and subtleties, nor does it provide sufficient natural light conditions to undertake a landscape character assessment.

- The assessment of the lighting of the Proposed Development is primarily intended to determine the likely significant effects on the visual resource i.e. it is an assessment of the visual effects of aviation lighting on views experienced by people at night. The matter of visible aviation and marine navigation lighting assessment is primarily a visual matter and the assessment presented focusses on that premise.

- The Scottish Government’s Aviation Lighting Working Group is working on guidance to streamline the process for night-time lighting assessments. While this guidance has yet to be published, there is some consensus that the perception of landform/skylines at night is a relevant consideration (with perception being a component of visual effects), however there is also widespread agreement that it is not possible to undertake landscape/coastal character assessment after the end of civil twilight, when it is technically 'dark' and wind turbine aviation lighting is switched on.

- To date the only formal recognition of this approach to assessment is the Scottish Ministers’ Decision for the Crystal Rig IV PLI. The Reporters concluded in their report at paragraph 4.141: “It can be seen from the summaries of evidence above that the parties differ as to whether the proposed aviation lighting would be a visual impact alone. We consider that without being able to see and fully appreciate the features of the landscape and the composition of views it is not possible to carry out a meaningful landscape character assessment. On this matter, we find that the proposed lighting is indeed a visual concern, as the applicant asserts.”

- In the absence of guidance being available, it is considered reasonable to adopt the findings of Scottish Ministers, following a detailed Public Inquiry as this represents precedence for focusing on the assessment of effects of turbine lighting as a visual matter.

- Assessment of proposed wind turbine lighting on coastal character at night is therefore focused on particular areas where the landform of the foreshore, coastal landforms and inshore islands etc may be perceived at night with lights in the background on the sea skyline i.e. where a perceived character effect may occur as a component of visual effects; and for particular designations where dark skies are a specific ‘special quality’ defined in their citation.

1.6.2. Significance criteria for night-time effects

- The nature of the daytime and night-time effects from visible aviation and marine navigation lighting are clearly very different, in that during day light hours visibility of moving WTG rotors gives rise to effects that are very different to the pinpoint effects of lighting at night. It is considered therefore, that the same criteria should not be used to assess these differences in daytime and night-time effect.

- In relation to the sensitivity of visual receptors, this is defined through the application of professional judgement in relation to the interaction between the ‘value’ of the view experienced by the visual receptor and the ‘susceptibility’ of the visual receptor (or ‘viewer’, not the view) to the particular form of change likely to result from the Proposed Development.

- The factors weighed in reaching a decision on ‘value’ of the view are not all applicable at night-time, in the same way they may be during the day. It is not appropriate, for example, to attribute value to views at night when the detail of the view, or of elements that add value to it within a landscape, cannot readily be discerned. Furthermore, the popularity of a viewpoint during the day may be completely different to its use at night. Value factors assessed for day-time viewpoints may therefore be of less relevance to the value judgement for night-time viewpoints, which is factored into the following assessments.

- In reaching a view on the significance of the likely visual effects from the visible aviation lighting, it is relevant to consider what parts of the landscape - where darkness qualities are well displayed - are likely to be affected by visibility of the aviation lights and, in turn, to understand what people might be doing in these areas at night to be susceptible to visibility of aviation lights. Descriptions of ‘susceptibility’ provided for daytime viewpoints and receptors in 1.5.3 are considered appropriate for the purposes of establishing receptor sensitivity at night-time, however the susceptibility of people experiencing night-time views will depend on the degree to which their perception is affected by existing baseline lighting. In brightly lit areas, or when travelling on roads from where sequential experience of lighting may be experienced, the susceptibility of receptors is likely to be lower than from within areas where the baseline contains no or limited existing lighting.

- In relation to the other key component in determining significance of effect, the magnitude of change, reference to ‘loss of important features’ and ‘composition of the view’ are not readily discernible or relevant at night and, on this basis, a distinct set of criteria to explain the magnitude of change at night, as a consequence of the appearance of aviation lights, is set out in Table 1.7 Open ▸ below.

Table 1.7: Magnitude of Change Criteria for Night-time Visual Effects

- The significance of effects of aviation and marine navigation lighting is assessed through a combination of the sensitivity of the visual receptor and the magnitude of change that would result from the visible aviation lighting, taking into account the considerations described above, and informed by the matrix in Table 1.10 Open ▸ , which gives an understanding of the threshold at which significant effects may arise.

- A significant effect occurs where the aviation and marine navigation lighting would provide a defining influence on a view or visual receptor. A not significant effect would occur where the effect of the aviation and marine navigation lighting is not material, and the baseline characteristics of the view or visual receptor continue to provide the definitive influence. In this instance the aviation lighting may have an influence, but this influence would not be definitive.

- In determining significance, particular attention is paid to the potential for ‘Obtrusive Light’ i.e. whether the lighting impedes a particular view of the night sky; creates sky glow, glare or light intrusion (ILP, 2011) in a prominent, incongruous or intrusive way.

1.7. Assessing seascape/landscape effects

1.7. Assessing seascape/landscape effects

1.7.1. Interface between SLVIA and Onshore LVIA

- Together, the SLVIA and the onshore Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment (LVIA) provide a whole project assessment of the effects of the Project. The offshore elements of the Project (the Proposed Development) are assessed in the SLVIA and the onshore elements of the Project (the onshore substation, onshore cable corridor, and landfall location) are assessed in the LVIA. Both the SLVIA and the LVIA follow a broadly similar assessment methodology that uses the same glossary and terminology.

- The SLVIA also provides an assessment of the cumulative effects likely to result from any areas where the construction, operation and decommissioning of the offshore and onshore elements combine to affect receptors within the SLVIA study area. An example could include effects on views where both offshore and onshore elements are visible, potentially resulting in cumulative landscape and visual effects as a result of the construction, operation and decommissioning of the offshore and onshore elements. These are assessed as part of the Tier 1 Cumulative Effects Assessment in Chapter 15 (Section 15.12).

- The SLVIA study area includes the intertidal area and this area is also considered as part of the onshore LVIA study area. The intertidal area at the proposed landfall incorporates the rock platform and shingle beach west of Chapel Point. As trenchless technology (e.g. horizontal directional drilling (HDD)) will be employed to bring the offshore export cable ashore, no physical disturbance of the beach or intertidal area is predicted.

1.7.2. Approach to Assessment of Seascape and Landscape Effects

- The Marine Policy Statement (MPS) (UK Government, 2011) states “references to seascape should be taken as meaning landscapes with views of the coast or seas, and coasts and the adjacent marine environment with cultural, historical and archaeological links with each other.”

- In England, seascape characterisation includes both the sea surface and what lies below the waterline, however in Scotland, ‘the focus is on the coast and its interaction with the sea and hinterland, relationships that are quite distinctive in the Scottish context’ (NatureScot, 2018).

- Given the definition in the MPS and the NatureScot coastal character assessment guidance, the assessment of seascape character effects in this SLVIA focuses on areas of onshore landscape with views of the coast or seas/marine environment, in other words the ‘coastal character’, on the premise that the most important effect of offshore wind farms is on the perception of the character of the coast.

- Coastal character is the ‘distinct, recognisable and consistent pattern of elements on the coast, land and sea that makes one part of the coast different from another’ (NatureScot, 2018) and is made up of the margin of the coastal edge, its immediate hinterland and areas of sea.

- The extent of the coast is principally influenced by the dominance of the sea in terms of physical characteristics, views and experience. The landward extent of the coast can be narrow where edged by cliffs or settlement; or broad where it includes raised beaches, dunes or more open coastal pasture or machair. The major determinant in defining the landward and seaward components of the coast is the sea - the key characteristic.

- Regional Coastal Character Areas (CCAs) are appropriate for the assessment of effects on coastal character. The coastal character of the SLVIA study area within Scotland is defined at the regional level within the Regional Seascape Character Assessment Aberdeen to Holy Island Suffolk (Forth and Tay Offshore Windfarm Developer Group, 2011).

- The Regional Seascape Character Areas defined in the FTOWDG Seascape Character Assessment are considered to equate to Regional CCAs as defined in the subsequent NatureScot Coastal Character Assessment Guidance (NatureScot, 2018) i.e. recognisable geographical areas with a consistent overall character at a strategic scale. Regional CCAs are shown as a simple colour line along the coast (Figure 15.3).

- Due to its scale, distance from shore and extent of visibility, it is necessary to consider the effects of the Proposed Development on both coastal character and landscape character.

- The effect of the Proposed Development on coastal (seascape) character is considered within the boundaries of defined coastal character areas (CCAs) and the immediately adjacent landscape character type (LCT) covering its hinterland, as defined in Figure 15.3, where there is a strong visual relationship with the sea/tidal waters and coastal landscapes such as dunes or cliffs.

- The effect of the Proposed Development on landscape character is considered on LCTs outside and inland of these CCAs and coastal LCTs, where there may be some intervisibility of the Proposed Development, but where the land is unlikely to have a strong visual relationship with the sea/tidal waters. These LCTs are identified in Figure 15.3 In general they are considered unlikely to experience significant character effects as a result of the Proposed Development because it is located in the sea, and these landscapes do not have a strong visual relationship with the sea and their character is fundamentally defined by other characteristics.

- Where detailed assessment of CCAs is required, effects are assessed on the discrete aspects of coastal character as defined in the coastal character assessment guidance (NatureScot, 2018) follows:

- Maritime influences and experience from the sea,

- Character of the coastal edge and its immediate hinterland,

- Extent of human activity, and

- Views and visibility (visual assessment).

- The assessment of effects on coastal character focuses upon the experiential characteristics that may be affected by the Proposed Development, rather than physical characteristics (which will not be affected by offshore development).

1.7.3. Seascape / landscape effects

- In respect of the Proposed Development, the potential seascape/landscape effects, occurring during the construction, operation and decommissioning periods of the Proposed Development may therefore include, but are not restricted to the following:

- changes to coastal character / landscape character and qualities: coastal/landscape character may be affected through the incremental effect on the perception of characteristic elements, landscape patterns and qualities (including experiential characteristics) and the addition of new features, the magnitude of which is sufficient to alter the perceived coastal character / landscape character within a particular area.

- changes to the perceived character of designated landscapes: that will affect the perceived special landscape qualities underpinning the designation and potentially its integrity.

- cumulative effects on coastal character / landscape character: where more than one development of a similar type may lead to a cumulative effect on the perception of coastal character or landscape character.

- Effects on coastal character and landscape character arising from the Proposed Development will be indirect effects, which will be perceived from the wider landscape, outside the Proposed Development array area.

Evaluating seascape/landscape sensitivity to change

- The assessment of sensitivity takes account of the seascape / landscape value and the susceptibility of the receptor to the Proposed Development.

- Seascape/landscape sensitivity often varies in response to both the type and phase of the development proposed and its location, such that sensitivity needs to be considered on a case by case basis. It should not be confused with ‘inherent sensitivity’ where areas of the landscape may be referred to as inherently of ‘high’ or ‘low’ sensitivity. For example, a National Park may be described as inherently of high sensitivity on account of its designation and value, although it may prove to be less susceptible (and therefore sensitive) to a particular development. The susceptibility of seascape/landscape receptors has been assessed in relation to change arising from the specific development proposed.

Sensitivity of seascape/landscape receptor

- The sensitivity of a seascape/landscape character receptor is an expression of the combination of the judgements made about the susceptibility of the receptor to the specific type of change or the development proposed, and the value related to that receptor.

Value of the seascape/landscape receptor

- The value of a seascape/landscape character receptor is a reflection of the value that society attaches to that seascape/landscape. The assessment of the seascape/landscape value has been classified as high, medium-high, medium, medium-low or low and the basis for this assessment has been made clear using evidence and professional judgement, based on the following range of factors.

- Seascape/landscape designations - A receptor that lies within the boundary of a recognised landscape related planning designation will be of increased value, depending on the proportion of the receptor that is affected and the level of importance of the designation which may be international, national, regional or local. The absence of designations does not however preclude value, as an undesignated landscape character receptor may be valued as a resource in the local or immediate environment.

- Seascape/landscape quality - The quality of a seascape/landscape character receptor is a reflection of its attributes, such as scenic quality, sense of place, rarity and representativeness and the extent to which its valued attributes have remained intact. A seascape/landscape with consistent, intact, well-defined and distinctive attributes is considered to be of higher quality and, in turn, higher value, than a landscape where the introduction of elements has detracted from its character.

- Seascape/landscape experience - The experiential qualities that can be evoked by a landscape receptor can add to its value and relates to a number of factors including the perceptual responses it evokes, the cultural associations that may exist in literature or history, or the iconic status of the seascape/landscape in its own right, the recreational value of the seascape/landscape, and the contribution of other values relating to the nature conservation or archaeology of the area.

Seascape / landscape susceptibility to change

- The susceptibility of a seascape/landscape character receptor to change is a reflection of its ability to accommodate the changes that will occur as a result of the addition of the Proposed Development without undue consequences for the maintenance of the baseline situation and/or the achievement of landscape planning policies and strategies. Some landscape receptors are better able to accommodate development than others due to certain characteristics that are indicative of capacity to accommodate change. These characteristics may or not also be special landscape qualities that underpin designated landscapes.

- The assessment of the susceptibility of the seascape/landscape receptor to change has been classified as high, medium-high, medium, medium-low or low and the basis for this assessment has been made clear using evidence and professional judgement. Indicators of landscape susceptibility to the type of development proposed (construction, operation and decommissioning of the Proposed Development) are based on the following criteria.

- Overall strength and robustness: Collectively the overall characteristics and qualities of a particular seascape/landscape result in a strong and robust landscape that is capable of reasonably accommodating the influence of the Proposed Development without undue adverse effects on the special landscape qualities (in the case of a designated landscape) or the key characteristics for which an area of seascape/landscape character or a particular element it is valued.

- Landscape scale and topography: The scale and topography are large enough to physically accommodate the influence of the Proposed Development. Topographical features such as more complex, distinctive or small-scale coastal landforms are likely to be more susceptible than simple, broad and homogenous coastal landforms.

- Openness and enclosure: Openness in the seascape/landscape may increase susceptibility to change because it can result in wider visibility, however open seascape/landscape may also be larger scale and simple, which will decrease susceptibility. Conversely, enclosed seascape/landscapes can offer more screening potential, limiting visibility to a smaller area, however they may also be smaller scale and more complex which will increase susceptibility. In general, large scale, simple and open seascapes/coastlines are likely to be less susceptible to the Proposed Development than more enclosed, complex seascapes/coasts (such as indented bays, headlands etc).

- Skyline: Prominent and distinctive skylines and horizons with important landmark features that are identified in the landscape character assessment, are generally considered to be more susceptible to development in comparison to broad, simple skylines which lack landmark features or contain other infrastructure features.

- Relationship with other development and landmarks: Contemporary landscapes where there are existing similar developments (WTGs or energy developments) or other forms of development (industry, mineral extraction, masts, urban fringe/large settlement, major transport routes) that already have a characterising influence result in a lower susceptible to development in comparison to areas characterised by smaller scale, historic development and landmarks.

- Perceptual qualities: Notable landscapes that are acknowledged to be particularly scenic, wild or tranquil are generally considered to be more susceptible to development in comparison to ordinary, cultivated or farmed / developed landscapes where perceptions of ‘wildness’ and tranquillity are less tangible. Landscapes which are either remote or appear natural may vary in their susceptibility to development.

- Landscape context and association: the extent to which the Proposed Development will influence the character of seascape/landscape receptors across the study area relates to the associations that exist between the seascape/landscape receptor within which the Proposed Development are located and the seascape/landscape receptor from which the Proposed Development is being experienced. In some situations this association will be strong, i.e., where the seascapes/landscapes are directly related, and in other situations weak (where the landscape association is weak). The context and visual connection to areas of adjacent seascape/landscape character or designations has a bearing on the susceptibility to development.

Seascape/landscape sensitivity rating

- An overall sensitivity assessment of the seascape/landscape receptor has been made by combining the assessment of the value of the seascape/landscape character receptor and its susceptibility to change. The evaluation of seascape/landscape sensitivity has been applied for each seascape/landscape receptor - high, medium-high, medium, medium-low and low - by combining individual assessments of the value of the receptor and its susceptibility to change. The basis for the assessments has been made clear using evidence and professional judgement in the evaluation of sensitivity for each receptor. Criteria that tend towards higher or lower sensitivity are set out in Table 1.8 Open ▸ below.

Table 1.8: Seascape/Landscape Sensitivity to Change

1.7.4. Seascape/landscape magnitude of change

- The magnitude of change on seascape/landscape receptors is an expression of the scale of the change that will result from the Proposed Development and is dependent on a number of variables regarding the size or scale of the change. The consideration of the size or scale of the effect, its geographical extent and its duration and reversibility are kept separate, by basing the magnitude of change primarily on size or scale to determine where significant and non-significant effects occur, and then describing the geographical extents of these effects and their duration and reversibility separately.

Size or scale of change

- This criterion relates to the size or scale of change to the seascape/landscape that will arise as a result of the Proposed Development, based on the following factors.

- Seascape/landscape elements: The degree to which the pattern of elements that makes up the seascape/landscape character will be altered by the Proposed Development, by removal or addition of elements in the seascape/landscape. The magnitude of change will generally be higher if the features that make up the seascape/landscape character are extensively removed or altered, and/or if many new offshore elements are added to the seascape/landscape.

- Seascape/landscape characteristics: This relates to the extent to which the effect of the Proposed Development changes, physically or perceptually, the key characteristics of the seascape/landscape that may be important to its distinctive character. This may include, for example, the scale of the landform, its relative simplicity or irregularity, the nature of the seascape/landscape context, the grain or orientation of the seascape/landscape, the degree to which the receptor is influenced by external features and the juxtaposition of the Proposed Development in relation to these key characteristics. If the Proposed Development are located in a seascape/landscape receptor that is already affected by other similar development, this may reduce the magnitude of change if there is a high level of integration and the developments form a unified and cohesive feature in the seascape/landscape.

- Seascape/landscape designation: In the case of designated landscapes, the degree of change is considered in light of the effects on the special landscape qualities which underpin the designation and the effect on the integrity of the designation. All landscapes change over time and much of that change is managed or planned. Often landscapes will have management objectives for ‘protection’ or ‘accommodation’ of development. The scale of change may be localised, or occurring over parts of an area, or more widespread affecting whole landscape receptors and their overall integrity.

- Distance: The size and scale of change is also strongly influenced by the proximity of the Proposed Development to the receptor and the extent to which the development can be seen as a characterising influence on the landscape. Consequently, the scale or magnitude of change is likely to be lower in respect of landscape receptors that are distant from the Proposed Development and / or screened by intervening landform, vegetation and built form to the extent that the scale of their influence on landscape receptors is small or limited. Conversely, landscapes closest to the development are likely to be most affected. Host landscapes (where the development is located within a ‘host’ landscape character unit) will be directly affected whilst adjacent areas of landscape character will be indirectly affected.

- Amount and nature of change: The amount of the Proposed Development that will be seen. Visibility of the Proposed Development may range from one WTG blade tip to all of the WTGs; generally, the greater the amount of the Proposed Development that can be seen, the higher the scale of change. The degree to which the Proposed Development is perceived to be on the horizon or ‘within’ the seascape/landscape. Generally, the magnitude of change is likely to be lower if the Proposed Development is largely perceived to be on the horizon at distance, rather than ‘within’ the seascape/landscape.

Geographical extent

- The geographic extent over which the seascape/landscape effects has been experienced is also assessed, which is distinct from the size or scale of effect. This evaluation is not combined in the assessment of the level of magnitude, but instead expresses the extent of the receptor that will experience a particular magnitude of change and therefore the geographical extents of the significant and non-significant effects.

- The extent of the effects will vary depending on the specific nature of the Proposed Development and is principally assessed through analysis of the extent of perceived changes to the seascape/landscape character through visibility of the Proposed Development.

- Landscape effects are described in terms of the geographical extent or physical area that will be affected (described as a linear or area measurement). This should not be confused with the scale of the development or its physical footprint. The manner in which the geographical extent of the seascape/landscape effect is described for different seascape/landscape receptors is explained as follows.

- Seascape/landscape character: The extent of the effects on seascape/landscape character will vary depending on the specific nature of the Proposed Development. This is not simply an expression of visibility or the extent of the ZTV, but also includes a specific assessment of the extent of landscape character that will be changed by the Proposed Development in terms of its character, key characteristics and elements.

- Landscape Designations: In the case of a designated landscape, this refers to the extent the special landscape qualities of the designation are affected and whether this can be defined in terms of area or linear measurements, or subjectively through professional judgement (with the support of an expert topic group and / or peer review) and whether the integrity of the designation is affected.

Duration and reversibility

- The duration and reversibility of seascape/landscape effects has been based on the period over which Proposed Development are likely to exist (during construction and operation) and the extent to which these elements has been removed (during decommissioning) and its effects reversed at the end of that period. Long-term, medium-term and short-term seascape/landscape effects are defined as follows:

- long-term – more than 10 years (may be defined as permanent or reversible);

- medium-term – 6 to 10 years; and

- short-term – 1 to 5 years.

1.7.5. Seascape/landscape magnitude of change rating

- The ‘magnitude’ or ‘degree of change’ resulting from the Proposed Development is described as ‘High’, ‘High-medium’, ‘Medium’, ‘Medium-low’ ‘Low’ or ‘Negligible’. In assessing magnitude of change, the assessment focuses on the size or scale of change. The geographic extent, duration and reversibility are stated separately in relation to the assessed effects (i.e., as short/medium / long-term and temporary/permanent). The basis for the assessment of magnitude for each receptor has been made clear using evidence and professional judgement. The levels of magnitude of change that can occur are defined in Table 1.9 Open ▸ .

Table 1.9: Seascape/Landscape Magnitude of Change Ratings

1.7.6. Evaluating seascape/landscape effects and significance

- The level of seascape/landscape effect is evaluated through the combination of seascape/landscape sensitivity and magnitude of change. Once the level of effect has been assessed, a judgement is then made as to whether the level of effect is ‘significant’ or ‘not significant’ as required by the relevant EIA Regulations. This process is assisted by the matrix in Table 1.10 Open ▸ which is used to guide the assessment. The factors considered in the evaluation of the sensitivity and the magnitude of the change resulting from the Proposed Development and their conclusion, has been presented in a comprehensive, clear and transparent manner.

- Further information is also provided about the nature of the effects (whether these will be direct/indirect; temporary/permanent/reversible; beneficial/neutral/adverse or cumulative).

- A significant effect will occur where the combination of the variables results in the Proposed Development having a defining effect on the seascape/landscape receptor, or where changes of a lower magnitude affect a seascape/landscape receptor that is of particularly high sensitivity. A major loss or irreversible effect over an extensive area or seascape/landscape character, affecting landscape elements, characteristics and / or perceptual aspects that are key to a nationally valued landscape are likely to be significant.

- A non-significant effect will occur where the effect of the Proposed Development is not defining, and the landscape character of the receptor continues to be characterised principally by its baseline characteristics. Equally a small-scale change experienced by a receptor of high sensitivity may not significantly affect the special landscape quality or integrity of a designation. Reversible effects, on elements, characteristics and character that are of small-scale or affecting lower value receptors are unlikely to be significant.

1.8. Evaluation of significance

1.8. Evaluation of significance

- The significance of the effect upon seascape, landscape and visual receptors is determined by correlating the magnitude of the impact and the sensitivity of the receptor, as presented in Table 1.10 Open ▸ .