Acronyms

Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

AA | Appropriate Assessment |

AEOI | Adverse Effect on Integrity (of a European site) |

AR3 | (CfD) Allocation Round 3 |

AR4 | (CfD) Allocation Round 4 |

BEIS | Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy |

BESS | British Energy Security Strategy |

CCC | Committee on Climate Change |

CES | Crown Estate Scotland |

CfD | Contract for Difference |

COP | The UN's Conference of the Parties |

Defra | Department for the Environment, Food & Rural Affairs |

EC | European Commission |

ECJ | European Court of Justice |

EIA | Environmental Impact Assessment |

EU | European Union |

GB / UK | Northern Ireland operates under a different electricity market framework to the rest of Great Britain (GB). Great Britain (GB) is referenced in relation to electricity generation and transmission, and Scotland, or the UK, are referenced as the nation(s) which have legally committed to Net Zero carbon emissions. |

GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

GIS | Geographical Information Systems |

GVA | Gross Value Added |

HND | Holistic Network Design |

HRA | Habitats Regulations Appraisal (or Assessment) |

INTOG | Innovation and Targeted Oil and Gas Decarbonisation (CES leasing round) |

IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

LAT | Lowest Astronomical Tide |

LCoE | Levelised cost of energy |

LSE | Likely Significant Effect |

MHWS | Mean High Water Springs |

MN 2000 | Managing Natura 2000 Sites |

MPA | Marine Protected Area |

MS-LOT | Marine Scotland Licensing Operations Team |

NETS | National Electricity Transmission System |

NPF | National Planning Framework (Scotland) |

NPS | National Policy Statements for Energy Infrastructure |

OWF | Offshore Wind Farm |

PIA | Project Identification and Approval process |

PDE | Project Design Envelope |

REZ | The UK Renewable Energy Zone. An area of sea outside the UK territorial sea over which the UK claims exclusive rights for production of energy from water and wind under section 84 of the Energy Act 2004. |

RIAA | Report to Inform Appropriate Assessment |

SAC | Special Area of Conservation (a type of European site) |

SMP | Sectoral Marine Plan for Offshore Wind Energy |

SNCB | Statutory Nature Conservation Bodies |

SofS | Secretary of State (for BEIS) |

SPA | Special Protection Area, for birds (a type of European site) |

STW | Scottish Territorial Waters |

TCE | The Crown Estate |

TEC | Transmission Entry Capacity |

UXO | Unexploded Ordinance |

ZAP | Zone Appraisal and Planning |

Executive Summary

Executive Summary

- The derogation case provides the reasons and evidence to enable Scottish Ministers to consent the offshore components of the Berwick Bank Wind Farm (the Proposed Development) under the Habitats Regulations Assessment (HRA) Derogation Provisions.

- The first section gives an overview of the Proposed Development and provides information on the relevant Scottish and UK legislation. A summary of the consultation is provided followed by a summary of the Report to Inform Appropriate Assessment (RIAA) and demonstrates how the Applicant has engaged with statutory and non-statutory consultees to develop a robust set of compensation measures. The Applicant’s position on Adverse Effect on Integrity (AEOI) is explained in relation to the different layers of precaution applied within the RIAA, and the need for a derogation case is set out.

- Two approaches have been taken in the RIAA to assess the potential for AEOI on the relevant Special Protection Areas (SPAs). The Scoping Approach has used the parameters advised in the scoping opinion. The Applicant has also presented an alternative assessment that uses parameters more in line with standard practice/ guidance – the Developer Approach

- Using the Scoping Approach, the RIAA concludes that an AEOI cannot be excluded at eight SPAs – Buchan Ness to Collieston Coast, East Caithness Cliffs, Farne Islands, Flamborough and Filey Coast, Forth Islands, Fowlsheugh and St Abbs to Fast Castle. Four species are affected – Kittiwake, Guillemot, Puffin and Razorbill.

- Using the Developer Approach, the RIAA concludes that an AEOI cannot be excluded at five SPAs. East Caithness Cliffs, Flamborough and Filey Coast, Forth Islands, Fowlsheugh and St Abbs to Fast Castle. Only Kittiwake is affected using this approach.

- Section Two gives more detail on the guidance and planning precedent that has informed the development of the derogation case and demonstrates that Applicant has considered in detail all the relevant information. Section Three provides a summary of the need for the Project and the key role that the Project must play in delivering Scottish and UK targets. This section is supported by an additional Statement of Need, which is provided with the application and demonstrates that the project is an essential part of the future generation mix.

- Without the Project, it is probable that delivery of a multitude of policies will fall short, including: the Scotland Sectoral Marine Plan, Scottish Energy Strategy, the Ten Point Plan, UK Net Zero Strategy and UK Offshore Wind Sector Deal, as well as the targets set by the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009, Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019, the (UK) Climate Change Act 2008 (as amended) and the Net Zero Strategy: Build back Greener.

- The next three sections deal with the legal tests that must be considered under the Habitat Derogation provisions. Firstly, alternative solutions to the Proposed Development are considered by identifying the core objectives of the project, then considering the “Do Nothing” scenario before assessing any feasible alternatives. A robust case is presented that sets out a comprehensive assessment of possible alternative locations and a range of potential alternative designs to meet the project objectives. In all cases no feasible alternative solutions were identified that could meet the project objectives.

- Secondly, the compelling case for authorising the Proposed Development for IROPI is made. The project must be carried out for imperative reasons given the urgent need to address climate change and meet legally binding targets. The long-term public interest of decarbonisation and security of supply of affordable energy supplies are in the overriding long-term public interest and demonstrably outweigh any AEOI which is predicted in respect of the identified SPAs.

- Finally, the process whereby the applicant has identified and assessed the feasibility of the necessary compensation measures is set out. The applicant has carried out extensive consultation and research to develop these measures and supporting information is provided in the three reports submitted with the application.

- Colony based compensatory measures evidence report – provides detailed information on the development of the colony measures and the quantification of predicted benefits

- Fisheries based compensatory measures evidence report - provides detailed information on the development of the colony measures and the quantification of predicted benefits

- Implementation and monitoring plan – provides an outline of the tasks and timelines to deliver the measures.

- The final part of this section demonstrates the sufficiency of the benefits that will be delivered by the proposed compensation measures and that the overall coherence of the national site network will be protected if they are implemented. These measures, assuming the worst case assessed in the RIAA and the most precautionary benefit from compensation measures, will provide very high compensation ratios of at least 8X the impacts. This provides considerable confidence to Scottish Ministers that the measures will be effective.

Part A: Background Information

Part A: Background Information

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

1.1. The Proposed Development Overview

1.1. The Proposed Development Overview

- Berwick Bank Wind Farm Limited (the Applicant) is proposing to develop the Berwick Bank Wind Farm (The Project), in the outer Firth of Forth and Firth of Tay within the former Round 3 Firth of Forth Zone.

- The Project will include offshore and onshore infrastructure including an offshore generating station (array), offshore export cables to landfall and onshore transmission cables leading to an onshore substation with electrical balancing infrastructure, and connection to the electricity transmission network. The offshore components of the Project seaward of MHWS are referred to as the Proposed Development.

- The array comprises 307 wind turbines, with an estimated capacity of 4.1 gigawatt (GW). The array will be approximately 47.6 km offshore of the East Lothian coastline and 37.8 km from the Scottish Borders coastline at St, Abbs. It lies to the south of the offshore wind farms (OWF) known as Seagreen and Seagreen 1A, south-east of Inch Cape OWF and east of Neart Na Goaithe OWF.

- The Proposed Development has secured Grid Connection Offers from National Grid Electricity System Operator (NGESO) for 4.1GW of Transmission Entry Capacity (TEC).

- A grid connection will run from the southern/south-western boundary of the array and make landfall at Skateraw on the East Lothian coast. The Applicant is also developing an additional export cable and grid connection to Blyth, Northumberland (the “Cambois connection”). Applications for the necessary consents (including marine licences) for the Cambois connection will be applied for separately once further development work has been undertaken on this offshore export corridor.

- Chapter 3 (Project Description) of the Offshore EIA Report provides a detailed description of the Proposed Development and should be referred to for further detail.

- The construction and operation of an OWF in Scottish waters (i.e., Scottish territorial waters (STW) and the Scottish offshore region) requires consent under Section 36 of the Electricity Act 1989 and Marine Licences under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 (within STW) and under the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 (within the Scottish offshore region, between 12 – 200 nautical miles (nm)).

- The Scottish Ministers are responsible for determining applications for Section 36 Consent and for Marine Licences. Where both are required, Marine Scotland’s Licensing Operations Team (MS-LOT) can process both applications jointly on behalf of the Scottish Ministers.

- This Report supports applications by the Applicant for Section 36 Consent and Marine Licences for the Proposed Development. As part of the Scottish Ministers determination of these applications, a Habitats Regulations Appraisal (HRA) is required under the applicable Habitats Regulations, as summarised in the following sections.

1.2. Origins of HRA: EU Habitats & Birds Directives

1.2. Origins of HRA: EU Habitats & Birds Directives

- The European Union (EU) Habitats Directive[1] and Wild Birds Directive[2] seek to conserve particular natural habitats and wild species across the territory of the EU by, amongst other measures, establishing a core network of sites for the protection of certain habitat types, species and wild birds (“European sites”).

- The overall aim is to ensure the long-term survival of viable populations of Europe's most valuable and threatened species and habitats, throughout their natural range, to maintain and promote biodiversity. European sites make up an EU-wide network known as “Natura 2000”.

- The UK has withdrawn from the EU. However, legislation transposing the Habitats and Birds Directives remains in place (subject to technical amendments), and case law and guidance referenced in this Report largely reflect or continue to refer to the Habitats and Birds Directives. Therefore, before turning to the UK legislation, it is useful to set out their terms for context.

- The protection and management of European sites is governed by Article 6 of the Habitats Directive. Amongst other things, Articles 6(3) and 6(4) lay down an assessment and permitting process concerning the authorisation of any plan or project likely to have a significant effect on any European site.

- Articles 6(3) and 6(4) prescribe a staged process: firstly, any such plan or project must be subject to an assessment to determine whether it would adversely affect the integrity of any European site and if so that plan or project may not proceed (Article 6(3)); secondly, a derogation process such that a plan or project found to adversely affect site integrity may still proceed, despite a negative assessment, if certain requirements are met (Article 6(4)). The full legal text is set out in Table 1 Open ▸ below.

Table 1 Legal text of Articles 6(3) and 6(4)

1.3. Scotland and UK Habitats Legislation

1.3. Scotland and UK Habitats Legislation

- Articles 6(3) and 6(4) of the Habitats Directive were transposed into UK law by, amongst others, the regulations identified in Table 2 Open ▸ below, each commonly referred to as the Habitats Regulations.

- Where in this Report the need arises to refer to a specific legislative provision, for simplicity reference is made only to The Conservation of Offshore Marine Habitats and Species Regulations 2017. However, the relevant provisions in the different sets of Habitat Regulations are materially the same and there is no legal or practical need to differentiate between them in this Report and the term Habitats Regulations is used as a collective reference encompassing all three sets of Regulations.

Table 2 Habitats Regulations relevant to the Proposed Development

- The procedure established by Articles 6(3) and 6(4) of the Habitats Directive relating to the authorisation of plans or projects, is known in Scotland as Habitats Regulations Appraisal (HRA) and is commonly regarded as a four stage process, which is summarised in Sections 1.4 and 1.5 below.

- In Scotland and the wider UK, the HRA process is applied, either as a matter of law or policy, to Special Areas of Conservation (SAC), Sites of Community Importance, candidate SACs and Special Protection Areas (SPAs), potential SPAs and possible SACs.

- The substantive HRA process and requirements are largely unchanged notwithstanding the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, albeit the Habitats Regulations have been subject to some technical changes. In particular, the Habitats Regulations continue to use the term “European sites”, but they now comprise a UK network which is called the “national site network” (previously they were part of Natura 2000). Therefore, references in the Habitats Regulations to the “coherence of Natura 2000" must now be read as references to the coherence of the UK’s "national site network".

1.4. Overview of HRA Stages 1 – 2: Screening and AA

1.4. Overview of HRA Stages 1 – 2: Screening and AA

- The Habitats Regulations require that a project[3]

- not directly connected with or necessary to the management of a European site, and

- “likely to have a significant effect” (LSE) on a European site (whether alone or in combination with another plan or project)

- must be subject to an “appropriate assessment” (AA) of the implications for that European site in view of the site's conservation objectives[4].

- The legal obligation to undertake an AA ultimately rests with the relevant “competent authority” under the Habitats Regulations. For the Section 36 Consent and Marine Licence applications, that is the Scottish Ministers[5]. However, the Applicant has an obligation to provide such information as the Scottish Ministers may reasonably require for the purposes of carrying out an AA[6].

- The identification of LSE is commonly referred to as HRA stage 1 and typically an applicant will conduct a screening exercise and provide an HRA Screening Report to inform this stage. The carrying out of an AA is commonly referred to as HRA stage 2 and typically an applicant will provide the Competent Authority with the necessary evidence and assessment in a Report to Inform an Appropriate Assessment (RIAA).

- Subject to a derogation process (HRA stages 3 and 4) as outlined in Section 1.5 below, a project can only be authorised if at the end of HRA stage 2, the competent authority is able to conclude, beyond reasonable scientific doubt in light of the findings of the AA, that the Proposed Development will not adversely affect the integrity of any European site(s).

- Further information on HRA stages 1 and 2 is contained in the Applicant’s RIAA and is not repeated here.

1.5. Overview of HRA Stages 3 & 4: Derogation Provisions

1.5. Overview of HRA Stages 3 & 4: Derogation Provisions

- The Habitats Regulations provide an exception to the general prohibition set out above, known as a “derogation”. A project can be allowed to proceed notwithstanding a conclusion that there will be an adverse effect on site integrity (AEOI) in respect of any European site(s) if the competent authority is satisfied that the following tests are met[7]:

- There are no alternative solutions to the project (Stage 3A); and

- There are “imperative reasons of overriding public interest” (IROPI) for the project to proceed (Stage 3B).

- If the Stage 3 requirements are met, the Scottish Ministers are then subject to a legal obligation to “secure that any necessary compensatory measures are taken to ensure that the overall coherence of the [national site network] is protected”[8] (HRA Stage 4).

- For ease of reference, the applicable legal text (hereinafter the HRA Derogation Provisions) which provide the framework for HRA Stages 3 and 4 is set out in Table 3 Open ▸ below. The process for HRA Stages 3 and 4 is addressed in extensive detail in Parts B, C and D of this Report.

Table 3 Relevant Scottish / UK Derogation Provisions[9]

1.6. HRA Process to Date & Applicant’s Position on AEOI

1.6. HRA Process to Date & Applicant’s Position on AEOI

- While ultimately it is the duty of the Scottish Ministers to apply the HRA process and to carry out an AA, the Applicant acknowledges it has an obligation to present such information as the Scottish Ministers may reasonably require for that purpose.

- To that end, the Applicant has compiled the necessary evidence and information to support an AA decision by the Scottish Ministers and this information is contained in the RIAA. The RIAA enables an AA of each relevant European site screened in for assessment.

- The Applicant’s RIAA has for the most part adopted the advice on ornithological assessment parameters advised in the Scoping Opinion. Nevertheless, the Applicant considers elements of the Scoping Opinion to be over-precautionary and a departure from standard advice/practice. As such, in the RIAA the Applicant has presented a dual assessment of potential displacement/barrier effects and collision effect pathways during operation based on:

- The ‘Scoping Approach’ and

- The ‘Developer Approach’.

- The Scoping Opinion contained advice on the displacement rates and displacement mortality rates. These rates have been used for the purposes of assessment under the Scoping Approach.

- Under the Developer Approach, these displacement rates differed in some cases, based upon available evidence for displacement, the extent of a features ranging behaviour (particularly in the non-breeding periods), previous precedent and a need to incorporate precaution within the assessment.

- Assumptions on the collision impacts for Kittiwake also differed between the Developer and Scoping approach.

- Table 4 Open ▸ sets out the annual adult bird mortalities[10] from the Proposed Development alone, apportioned to each SPA where the Scoping Approach has found an AEOI. For the majority of features a conclusion of AEOI is due to the in-combination effect of other plans and projects. Only for two features at three SPAs was an AEOI identified from the Proposed Development alone (guillemot at Forth Islands, Fowlsheugh and St Abb's Head to Fast Castle, and kittiwake at St Abb's Head to Fast Castle).

- If Scottish Ministers choose to adopt this assessment approach, kittiwake, razorbill, guillemot and puffin would require compensatory measures to be secured at the SPAs listed in Table 4 Open ▸ .

Table 4 SPAs and qualifying features for which AEOI has been concluded based on the scoping approach to calculate adult mortality. The mortalities for kittiwake represent a combined impact value for collision and displacement. The mortalities for all other species are a result of displacement only

- Table 5 Open ▸ sets out the annual adult bird mortalities from the Proposed Development alone, apportioned to each SPA where the Developer Approach has found an AEOI. In all but one SPA (kittiwake at St Abbs Head to Fast Castle) an AEOI was due to the in-combination effect of other plans and projects.

- If Scottish Ministers choose to adopt this assessment approach, only kittiwake would require compensatory measures to be secured at the SPAs listed in Table 5 Open ▸ .

Table 5 SPAs and qualifying features for which AEOI has been concluded based on the developer approach to calculate adult mortality. The mortalities for kittiwake represent a combined impact value for collision and displacement. The mortalities for all other species are a result of displacement only.

- The Applicant is confident that the Developer Approach is the most appropriate methodology for the RIAA as the scoping approach is over-precautionary. Nevertheless, the Applicant has provided the necessary information and justification (the Derogation Case) to satisfy the HRA Derogation Provisions in respect of all features identified under the scoping approach. This demonstrates that sufficient compensation can be secured for any scenario for which the RIAA has found an AEOI.

- It should be noted that, in addition to several Scottish SPAs, both approaches have identified an AEOI at English SPAs. In circumstances where AEOI are identified for a European site outside Scotland or the Scottish offshore region, the Scottish Ministers must notify the Secretary of State (SofS) and can only agree to the Proposed Development after having been notified of the SofS’s agreement.

- As such, this Report provides a comprehensive Derogation Case that can be relied upon by the Scottish Ministers and SofS to the extent required.

1.7. Summary of Consultation to Date

1.7. Summary of Consultation to Date

- The Applicant recognises the importance of engaging with relevant stakeholders with respect to its Derogation Case, in particular with statutory nature conservation bodies (SNCBs) with regards to the development of potential compensation measures.

- The Applicant has sought the advice of the SNCBs and other key stakeholders and kept them updated on project developments. The Applicant has engaged openly and transparently including by issuing an initial questionnaire and / or undertaking interviews, followed by a series of online meetings from October 2021 to November 2022, including with NatureScot, MS-LOT, RSPB, Scottish Seabird Centre, Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, National Trust for Scotland, National Trust, Scottish Wildlife Trust, a local ornithological consultant, local bird ringer/ornithological experts, Defra, SFF, FRS, Seabird centre Board and Natural England. A full report of consultation carried out specifically with regard to derogation and compensation matters is provided in Appendix 1 of this document. A summary of the wider consultation process carried out for the Project is set out in Volume 1 Chapter 5 Stakeholder Engagement and Consultation of the EIA.

1.8. Supporting Information

1.8. Supporting Information

- Report to Inform Appropriate Assessment

- Statement of Need

- Offshore Planning Statement

- Enhancement, Mitigation and Monitoring Commitments (Volume 3, Appendix 6.3)

- Offshore EIA: Project Description (Volume 1 Chapter 3)

- Offshore EIA: Site Selection and Consideration of Alternatives (Volume 1 Chapter 4)

- Onshore EIA: Socioeconomics (Volume 1 Chapter 13)

- Offshore EIA: Socioeconomics (Volume 1 Chapter 18)

- Socio-Economics and Tourism Technical Report (Volume 3 Appendix 18.1)

- Implementation and Monitoring Plan

2. HRA Derogations Guidance and Precedent

2. HRA Derogations Guidance and Precedent

2.1. Introduction

2.1. Introduction

- This section provides an overview of the guidance and precedent relating to HRA Stages 3 and 4: No Alternative Solutions, IROPI and Compensatory Measures.

2.2. Guidance

2.2. Guidance

- In preparing this Report a range of guidance has been reviewed and drawn upon, as listed below:

Scottish Guidance

- SNH (2010). SNH Guidance ‘Natura sites and the Habitats Regulations. How to consider proposals affecting SACs and SPAs in Scotland. The essential quick guide’.

- DTA (2015) Habitats regulations appraisal of plans: Guidance for plan-making bodies in Scotland.

- Scottish Government (2015). Scotland’s National Marine Plan: A Single Framework for Managing Our Seas.

- Scottish Government (2020a). Policy paper ‘EU Exit: The Habitats Regulations in Scotland’.

- DTA Ecology (2021a: in draft). Policy guidance document on demonstrating the absence of Alternative Solutions and imperative reasons for overriding public interest under the Habitats Regulations for Marine Scotland.

- DTA (2021b) Framework to Evaluate Ornithological Compensatory Measures for Offshore Wind. Process Guidance Note for Developers. Advice to marine Scotland.

UK Guidance

- Defra (2012). Habitats Directive: guidance on the application of article 6(4).

- Defra (2021a) Habitats regulations assessments: protecting a European site

- Defra (2021b). Draft best practice guidance for developing compensatory measures in relation to Marine Protected Areas.

- DTA (2021) The Habitats Regulations Assessment Handbook.

EU Guidance

- EC (revised 2018). Managing Natura 2000 Sites (MN 2000): The provisions of Article 6 of the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC.

- EC (revised 2021). Guidance document on wind energy developments and EU nature legislation

- EC (revised 2021). Methodological guidance on the provisions of Article 6(3) and (4) of the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC and Annex (the EC Methodological Guidance);

- The Scottish Government recently provided draft guidance on HRA stages 3 and 4, specifically for offshore wind in Scotland, to OWF developers for comment. This draft guidance is divided into Alternative Solutions and IROPI (DTA, 2021a: in draft) and compensation measures (DTA 2021b)[11].

- This draft guidance is referenced in this Report; however, its status is currently unknown and no particular reliance is placed upon it. The draft DTA guidance is generally a restatement of principles evident from European, UK and/or Scottish jurisprudence or guidance. As such, whilst the draft DTA guidance (if formalised) is a useful additional resource, it did not introduce new principles or concepts which are necessary to be relied upon in this case. If it is not subsequently adopted by the Scottish Government, the principles referred to and relied upon in this Report remain valid and supporting references have been provided where relevant.

2.3. EC Opinions

2.3. EC Opinions

- Where it is proposed to rely upon an HRA derogation concerning a European site hosting a priority habitat and/or a priority species, in certain circumstances it is necessary for EU member states to obtain an opinion from the EC[12]. Following the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, the UK is no longer subject to this requirement.

- The EC has adopted and published a number of opinions on Article 6(4) derogation cases between 1996 and 2022[13]. These EC opinions have also been reviewed and considered; however each EC opinion is project and fact specific and none concern an OWF project. Furthermore, all of the opinions concern cases concerning priority habitat and/or priority species, which is not applicable in this case.

2.4. Planning Precedent

2.4. Planning Precedent

- To date no HRA derogation cases for an OWF in Scottish waters have been submitted to or relied upon by the Scottish Ministers. However, in the wider UK, there have been five OWF which have received consent pursuant to a derogation. None of these decisions has been subject to legal challenge on grounds relating to the approach taken for the HRA derogation.

- In the absence of planning decisions for Scottish OWF which rely upon an HRA derogation, it is appropriate and useful to consider and refer to UK OWF planning decisions as a guide on the types of evidence and scenarios. These UK OWF planning decisions have been made under the same legal framework[14], against the background of the same guidance set out above.

- The five OWF derogation cases to date have been considered by the SofS for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and all concern OWF in the North Sea. These are:

- Hornsea Three OWF (Hornsea Three) (BEIS, 2020);

- Norfolk Boreas OWF (Norfolk Boreas) (BEIS, 2021);

- Norfolk Vanguard OWF (BEIS 2022);

- East Anglia ONE North OWF (BEIS 2022); and

- East Anglia TWO OWF (BEIS 2022).

- There is one other OWF application which has presented a “without prejudice” derogation case (Hornsea Four, also in the North Sea, off the East Coast of England). A decision by the SofS on the Hornsea Four consent application is expected in February 2023.

- The most recent example of an offshore wind related HRA derogation case is The Crown Estate’s plan-level HRA for its Round 4 offshore wind leasing process. Following completion of its AA, The Crown Estate (TCE) concluded there was a risk of an AEOI with regards to the kittiwake feature of the Flamborough and Filey Coast SPA in-combination, and the sandbanks feature of the Dogger Bank SAC, alone or in-combination. As such, TCE prepared an HRA derogation case which was subsequently approved by BEIS allowing the Round 4 plan to proceed.

- A summary of applications which have included an HRA derogation cases is provided in Table 6 Open ▸ . Each example demonstrates how the HRA Derogation Provisions and associated guidance can be relied upon to consent OWFs (plan or project level), notwithstanding the identification of AEOI.

Table 6 OWF Derogation Cases relevant to The Proposed Development

3. Summary of Need Case

3. Summary of Need Case

3.1. Introduction

3.1. Introduction

- As will be seen in Part B and Part C of this Report, HRA Stages 3A (Alternative Solutions) and 3B (IROPI) are intertwined with and framed by the need for a given project. It is convenient to address the topic of need at this stage, to inform and limit later repetition in Parts B and C of this Report.

- The factors which support and define the clear and urgent need case for The Project are set out comprehensively in the Applicant’s Statement of Need and Offshore Planning Statement and are only summarised below.

- In short, the need case is predicated upon the critical contribution of The Project to four important pillars of energy policy:

- Decarbonisation, to achieve “Net Zero” as soon as possible, to mitigate climate change;

- Security of supply: geographically and technologically diverse supplies;

- Affordability, energy at lowest cost to consumers;

- Action before 2030: time is of the essence, meaning early deployment, at scale, is critical (owing to 1 – 3 above).

3.2. Climate Change, Net Zero and Decarbonisation

3.2. Climate Change, Net Zero and Decarbonisation

The Climate Emergency

- Climate change is the defining challenge of our time. The impacts of climate change are global in scope and unprecedented in human existence.

- The United Nations (UN) has been leading on global climate summits (‘Conference of the Parties”, COP) for nearly three decades. International consensus on the need to tackle climate change is reflected in The Paris Agreement[15], adopted at COP21 in 2015 by 196 parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. For the first time it created a legally-binding, international agreement towards tackling climate change. The UK (and hence Scotland) is legally bound to the Paris Agreement. The member governments agreed:

- A long-term goal of keeping the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels;

- To aim to limit the increase to 1.5°C since this would significantly reduce risks and the impacts of climate change;

- On the need for global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to peak as soon as possible; and

- To undertake rapid reductions thereafter in accordance with the best scientific guidance available.

- This international ambition underpins subsequent Scotland and UK legislation on climate change mitigation, addressed below.

- However, despite action to date, human-induced warming has reached approximately 1ºC above pre-industrial levels, as confirmed by the recent Inter-Governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 6th Assessment Report (the AR6 Report), published in three parts across 2021 and 2022. The AR6 Report is the first major review of the science of climate change since 2013 and is addressed in further detail in the Applicant’s Planning Statements and Statement of Need. Some of the key messages are as follows:

- Without immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in GHG, limiting warming close to 1.5°C or even 2°C will be beyond reach.

- Delay in concerted global action will miss a brief and rapidly closing window to secure a liveable future.

- Limiting warming to around 1.5°C requires global GHG emissions to peak before 2025 at the latest, and be reduced by 43% by 2030

- Limiting global warming will require major transitions in the energy sector. This will involve a substantial reduction in fossil fuel use, widespread electrification, improved energy efficiency and use of alternative fuels.

- Thus, a key theme of the AR6 Report is that humanity is not on track to limit warming to the extent necessary, but that it is still just about possible to make the necessary progress by 2030 by, for example, moving rapidly to non-fossil fuel sources of energy. The next few years are critical.

Net Zero

- The Scottish Government has recognised the gravity of the situation described above. Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon declared a "Climate Emergency" in her speech to the SNP Conference in April 2019. Climate Change Secretary Roseanna Cunningham subsequently made a statement to the Scottish Parliament on 14 May on the 'Global Climate Emergency' and said:

"There is a global climate emergency. The evidence is irrefutable. The science is clear and people have been clear: they expect action. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued a stark warning last year - the world must act now. By 2030 it will be too late to limit warming to 1.5 degrees.” [emphasis added].

- An emergency is, by definition, a grave situation that demands an urgent response.

- In Scotland and the UK legal obligations to achieve Net Zero, to mitigate climate change, have accordingly been strengthened in recent years as follows:

- Scotland: the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 was amended by the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019; and

- UK: the Climate Change Act 2008 was amended by the Climate Change Act 2008 (2050 Target Amendment) Order 2019.

- The Scottish and UK Governments are now legally bound to reach Net Zero (i.e. ensure that their respective net carbon account is at least 100% lower than the 1990 baseline) by 2045 in Scotland and by 2050 in the UK.

- Challenging interim ‘stepping-stone’ targets are also in place. Scotland has interim targets of a 75% reduction target by 2030 and 90% by 2040. The 75% target by 2030 is especially challenging. The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) modelled five scenarios in CB6 and none – even the optimistic scenario – shows Scotland achieving a 75% emissions reduction by 2030. The CCC has therefore stated:

“Scotland’s 75% target for 2030 will be extremely challenging to meet, even if Scotland gets on track for net zero by 2045. Our balance net zero pathway for the UK would not meet Scotland’s 2030 target – reaching a 64% reduction by 2030 – while our most stretching tail winds scenario reaches a 69% reduction”.

- COP26 was held in Glasgow in November 2021, allowing Scotland to demonstrate international leadership on climate change. COP26 recognised the urgent need to further reduce emissions before 2030 and parties made a commitment to revisit and strengthen their current emissions targets to 2030, in 2022. Agreements made at COP26 were detailed in the Glasgow Climate Pact (UNFCC, 2021[16]). Paragraph 17 states that “rapid, deep and sustained reductions in global greenhouse emissions” are required to limit temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial times.

- The twenty seventh COP (COP27) took place in Sharm el-Sheikh in November 2022. The COP expressed “alarm and utmost concern that human activities have caused a global average temperature increase of around 1.1 °C above pre-industrial levels to date and that impacts are already being felt in every region and will escalate with every increment of global warming”[17] and agreed a package of decisions[18] which reaffirmed their commitment to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. However, it was acknowledged that current policies and actions are insufficient to achieve that objective.

- The backdrop to COP27 was a report from UN Climate Change[19], which indicates that implementation of current pledges by national governments put the world on track for a 2.5°C warmer world by the end of the century. Therefore, despite some notable breakthroughs, such as an agreement to provide “loss and damage” funding for vulnerable countries hit hardest by climate disasters, in his closing remarks, Simon Stiell, UN Climate Change Executive Secretary, reminded delegates that the 2020s are a critical decade for climate action. Governments were tasked with revisiting and strengthening the 2030 targets in their national climate plans by the end of 2023, as well as accelerate efforts to phasedown unabated coal power and phase-out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.

- In the field of energy, the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan[20] repeated “the urgent need for immediate, deep, rapid and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions …across all applicable sectors, including through increase in low-emission and renewable energy,”. However, the Implementation Plan also recognised the importance of energy security of supply. It described an “unprecedented global energy crisis” which “underlines the urgency to rapidly transform energy systems to be more secure, reliable, and resilient, including by accelerating clean and just transitions to renewable energy during this critical decade of action”. This energy security of supply crisis underscores the importance of “enhancing a clean energy mix, including low-emission and renewable energy, at all levels as part of diversifying energy mixes and systems, in line with national circumstances and recognizing the need for support towards just transitions”.

- In effect, the Scottish and UK Governments, in common with COP, have agreed that, beyond their own national targets, more must and can be done. This implies a greater target capacity of carbon-neutral power supply than currently pledged and a more rapid timeline for decarbonisation wherever possible.

Decarbonisation

- Decarbonisation is the act of reducing the carbon footprint (primarily in the form of GHG) arising from the use of energy in society, to reduce the warming impact on the global climate.

- The adoption of Net Zero commitments as described above requires a substantial reduction in the carbon emissions from transport, heat and industrial emissions.

- This is reflected in Scottish and UK policy. The Scottish Energy Strategy (2017) establishes targets for 2030 to supply the equivalent of 50% of the energy for Scotland’s heat, transport and electricity consumption from renewable sources; and to increase by 30% the productivity of energy use across the Scottish economy (Scottish Government, 2017). Similarly, the UK Clean Growth Strategy (BEIS 2017) provides measures to decarbonise all sectors of the UK economy through the 2020s and beyond.

- However, while multiple pathways for the energy mix could achieve the previous 80% C-reduction target, Net Zero leaves a narrower choice of pathways which will lead to success[21] and there is presently a gap between ambition and reality.

Ambitions Vs Reality Gap

- Figure 1 below shows the gap in carbon emissions between current global decarbonisation policies, current pipelines and pledges, and (in green) the pathway required to be followed to ensure that global warming does not increase over 1.5C by 2100.

Figure 1 Global 2100 Warming Projections[22]

- The world is lagging in decarbonisation progress and because carbon has a cumulative warming effect, targets associated with decarbonisation have correspondingly increased year-on-year. Therefore, although Scotland and the UK are leading decarbonisation efforts, their respective legal commitments of achieving Net Zero by 2045 and 2050 respectively are not assured. The climate challenge is such that there is currently no limit or cap to the benefit that single countries can bring in the fight against global warming.

The Need for AdditIonal Electricity Generating Capacity

- Electricity generation is an important sector for climate change because, although historically a significant carbon emitter, it is now the critical enabler of deep decarbonisation across society. The decarbonisation of electricity is critical for Net Zero to be achieved and deeper decarbonisation requires deeper electrification.

- Figure 2 below shows how National Grid’s Future Energy Scenarios electricity demand forecasts for GB have evolved from 2012 through to 2022.

Figure 2 Future Energy Scenarios demand forecasts 2012-2022[23]

- Historical annual GB electricity demand is represented by the purple columns (declining with de-industrialisation and energy efficiency measures) and each yearly forecast is represented by a shaded area which shows the max and min forecast range per year for those scenarios which are compatible with Net Zero 2050.

- Following the 2019 enshrinement into law of the Net Zero commitments, the 2020 and 2021 forecasts show a significant uplift versus previous year forecasts and are coloured blue for emphasis. The most recent forecast is bordered with a thin blue line.

- Important points to note from Figure 2 are:

- Each year the forecast for electricity demand has increased, as the need to decarbonise has grown.

- Deeper decarbonisation draws power from other primary fuels (carbon intensive) to electricity which may, and needs, to be generated from low-carbon sources.

- Since Scotland and the UK committed to Net Zero, forecast future electricity demand has increased significantly and is now as high as it ever has been.

- UK government forecasts for electricity demand in the 2050 timeframe use the value of 600TWh/year – double today’s consumption – and this includes Scottish demand[24].

The Need for Additional Offshore Wind Deployment, at Scale

- The UK has plentiful wind resource. Therefore, a significant focus of Scottish and UK energy policy is the vital role and need for rapid large-scale deployment of GWs of offshore wind. The policy is detailed fully in the Applicant’s Offshore and Onshore Planning Statements and Statement of Need but include:

- Revised National Planning Framework 4[25] – offshore wind developments proposed in excess of 50MW are categorised as “national development” (Strategic Renewable Electricity Generation and Transmission Infrastructure), the need for which is assumed.

- Offshore Wind Policy Statement[26] – sets an ambition for up to 11 GW of OWF by 2030;

- Scotland’s Energy Strategy Position Statement[27] – identifies offshore wind as a major component of Scottish energy strategy from the perspective of being an important low-carbon primary energy generator and from the perspective of continuing to develop world-leading support and development services to the global offshore wind industry.

- Scotland Sectoral Marine Plan for Offshore Wind[28] - identifies 15 Plan Option areas, split across 4 regions in Scottish waters, capable of generating up to 10 GW of renewable energy.

- Scotland’s National Marine Plan (2015) - includes the objectives of sustainable development of offshore wind in suitable locations, to contribute to achieving the decarbonisation target by 2030

- HM Government British Energy Strategy (2022) targeting 50 GW offshore wind by 2030

- Net Zero Strategy for the UK (HM Government, 2021a),

- Build Back Greener (HM Government, 2021a) goes on to take action so that by 2035, all the UK’s electricity will come from low carbon sources, including offshore wind;

- UK Offshore Wind Sector Deal (BEIS 2019)

- Energy White Paper (HM Government, 2020b);

- National Policy Statements (NPS) for England and Wales and draft NPS (EN-1, EN-3, EN-5)[29].

- Electricity System Operator National Grid ESO: Future Energy Scenarios requirement for 38 – 47 GW offshore wind in 2030, 68 – 83 GW in 2040, and 87 – 113 GW by 2050[30].

- In short, the need for a massive amount of additional offshore wind capacity is a very strong and constant theme of all extant Scottish and UK energy policy.

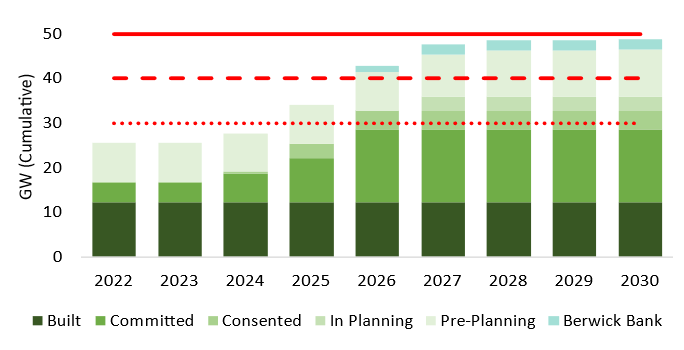

- National Grid’s Future Energy Scenarios contemplates the requirement for offshore wind (and other technologies) required to meet the forecast growth in electricity demand. Figure 3 below shows the forecast capacity of offshore wind from National Grid’s Future Energy Scenarios, with the same format protocol as shown in Figure 2 above.

Figure 3 Future Energy Scenarios offshore wind capacity forecasts 2012-2022[31]

- Key points to note from Figure 3 are:

- Although the UK is leading the world in offshore wind, the currently installed capacity is significantly lower than it needs to be according to National Grid future energy scenarios.

- Since Net Zero, offshore wind is expected to play an enormous part in meeting the electricity needs of the UK in the future.

- In every scenario, a pathway to Net Zero includes a significant increase of offshore wind capacity (beyond that predicated in the Offshore Wind Sector Deal).

- Even “low-case” projections for offshore wind deployment – in which Net Zero will be met only if “hi-cases” for other technologies such as nuclear, CCUS, solar and onshore wind are met – represent a significant growth in installed capacity from today onwards.

- Importantly, these offshore wind projections need to be read and pursued in the knowledge that there is attrition during project development and not all proposed offshore wind projects reach commercial operation, and some do so at reduced scale, or later than planned. Therefore, consenting a much larger offshore wind capacity than provided for in the various targets, as quickly as possible, is necessary to meet Net Zero.

- In its 2021 progress report[32], the CCC emphasised that to achieve Net Zero requires a “rapid scale up in low carbon investment…..and speed up the delivery which will need to accelerate even where ambition is broadly on track. For example, although the Government’s 2030 target for offshore wind is in line with the CCC pathway, a minimum of 4 GW of additional offshore wind capacity will be needed each year from the mid-2020s onwards, significantly greater than the current 2 GW per year”. It should be noted that the target referred to in the above extract is the previous target of 40GW by 2030, which suggests that more than 4GW per year growth in offshore wind capacity is required from the mid-2020s to achieve the 50GW target.

- In conclusion, a massive increase in energy generation from offshore wind is important to reduce electricity-related emissions, and to provide a timely next-step contribution to a future generation portfolio which is capable of supporting the massive increase in electricity demand, which is expected because of decarbonisation through-electrification of transport, heat and industrial demand.

3.3. Security of Supply

3.3. Security of Supply

- Energy security is a key pillar of energy policy at Scottish, UK and EU levels.

- Although Scotland has its own decarbonisation targets, the connectedness of the electricity systems across Great Britain means that security of supply and decarbonisation of the electricity sector need to be considered at the GB level. The electricity systems of Scotland, Wales and England are essentially one system.

- Security of supply means keeping the lights on. That entails, amongst other things, ensuring that there is enough electricity generation capacity available to meet maximum peak demand (not just average demand), and with a safety margin or spare capacity to accommodate unexpectedly high demand and to mitigate risks such as unexpected plant closures and extreme weather events.

- And while technologies such as batteries or hydrogen will ensure that peak demand is met by storing energy at times of oversupply and discharging it at times of overdemand, more renewable generation capacity is required to meet demand than would be required of conventional generation, because of its intermittent nature.

- Recent European events have challenged the UK’s prevailing view on and approach to energy security, in particular UK dependency on foreign hydrocarbons. The British Energy Security Strategy (BESS), which applies across GB, was published by BEIS following concerns over the security of international hydrocarbon supplies and increasingly volatile international markets in early 2022.

- Reducing the UK’s dependency on hydrocarbons is already essential for decarbonisation but recent world events have brought into sharp focus that reducing dependency on foreign hydrocarbons has important security of supply, electricity cost and fuel poverty avoidance benefits. Actions already urgently required in the fight against climate change are now required even more urgently for global political stability and insulation against dependencies on other nation states.

- The UK imports 100 Million Tonnes of Oil Equivalent (MTOE) of coal, oil and gas each year. Of this, approximately 8 MTOE arrives from Russia. 8 MTOE is equivalent to approximately 93 TWh of energy[33]. 8 MTOE is equivalent to approximately 93 TWh of energy[34].

- 1 GW of offshore wind, at a conservatively assumed load factor of 48%, has the potential to generate 4.2TWh/year, or 4.5% of Russian energy imports averaged over 2019/2020. This metric also demonstrates the enormous challenge ahead to achieve national independence on Russian energy imports. The equivalent of 5 x Berwick Banks are needed to remove the need for any energy imports from Russia.

- A diverse mix of all types of power generation helps to ensure security of supply, however a low-cost, net zero consistent system is likely to be composed predominantly of wind and solar[35]. The diversification of the GB’s electricity supplies through the commissioning of offshore wind assets to the NETS, alongside other low carbon generation technologies, provides benefits in the functioning of the NETS and ensuring power is available to consumers across the country when it is required, due to its requirement to operate within the stringent operability and control requirements of the Grid Code[36].

- As part of a diverse generation mix, wind generation contributes to improve the stability of capacity utilisations among renewable generators. By being connected at the transmission system level, large-scale offshore wind generation can and will play an important role in the resilience of the GB electricity system from an adequacy and system operation perspective. Further generation of offshore wind in Scotland will avoid the need for more / extended imports of electricity from the wider UK to meet its growing electricity demand. It will also ensure a lower carbon content of electricity owing to Scotland being further ahead than the wider UK in decarbonising its electricity supply.

- This demonstrates how offshore wind has, and must continue to contribute, to security of supply for GB consumers through being a dependable supply of low carbon power. Further details are set out in the Applicant’s Statement of Need.

3.4. Affordability

3.4. Affordability

- In Just Transition: A Fairer, Greener Scotland[37], the Scottish Government identified its priority to achieve a “just transition” to Net Zero, that is to deliver the desired outcome – a net zero and climate resilient economy – in a way that delivers fairness and tackles inequality and injustice.

- The UK and especially Scotland has plentiful wind resource and costs are competitive versus other technologies, which is an important factor in ensuring affordability for consumers. This is reflected in the Offshore Wind Policy Statement[38], which states (page 2):

“Offshore wind is one of the lowest cost forms of electricity generation at scale, offering cheap, green electricity for consumers, with latest projects capable of generating power at below wholesale electricity prices.”

- Cost reduction and affordability have been particularly important in the development of OWF development. UK policy and regulatory objectives seek to ensure affordability to consumers, through the Contract for Difference (CfD) auction process (generation assets) and Offshore Transmission Owner regime (offshore transmission assets).

- In broad terms, both seek to incentivise investment in low carbon electricity generation and transmission assets, ensure security of supply and help the UK meet its carbon reduction and renewables targets, whilst reducing cost to the consumer.

- The CfD mechanism plays a very important role in bringing forwards new large-scale low carbon generation, and Allocation Round 4 (AR4) contracts awarded in the summer of 2022 provide an indicator of the importance of wind as a technology class within the GB electricity system, and an indicator of the competitive cost of the technology: over 8.5GW of wind capacity across 22 projects secured Contracts for Difference in AR4, at an initial strike price ranging from £37.35/MWh (Offshore Wind) to £87.30/MWh (Floating Offshore Wind). All CfDs commence in either 2024/25 (Onshore Wind) or 2026/27 (all Offshore Wind technologies).

- As a result, Scottish and UK OWF projects are increasing in capacity, and decreasing in unit cost. Hitherto, each subsequent project has provided a real-life demonstration that size and scale works for new offshore wind, for the benefit of consumers. Other conventional low-carbon generation (e.g. tidal, nuclear or conventional carbon with Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage) remain important contributors to achieving the 2050 Net Zero obligation, but their contributions will not be significant in the 2020s due to the associated technical, commercial and development timeframes.

- For the reasons summarised above, the economic and technical competitiveness for offshore wind makes it the preferential power supply to the Scotland and GB electricity consumer. Further details are set out in the Applicant’s Statement of Need.

3.5. The Need for Action Before 2030

3.5. The Need for Action Before 2030

- Both the Scottish Energy Strategy[39] and the UK Net Zero Strategy[40] make a case for a low or no regrets approach to decarbonisation. This framework, set by the Nation Engineering Policy Centre (2017) promotes rapid decision making in net zero policy in order to make urgent progress.

- The Scottish Energy Strategy thus sets a 2030 target to supply the equivalent of 50% of the energy for Scotland’s heat, transport and electricity consumption from renewable sources; and to increase by 30% the productivity of energy use across the Scottish economy. Scotland’s Offshore Wind Policy Statement in turn sets an ambition (but not limit) for 11 GW of offshore wind capacity in operation in Scottish waters by 2030.

- There is good reason for this focus on near-term action before 2030. The need for decarbonisation grows stronger each year. Every year during which no action is taken, more carbon is released into the atmosphere, global temperatures rise and the global warming effect accelerates. A rise in global temperatures above 1.5°C has potential to cause irreversible climate change, the potential for widespread loss of life and severe damage to livelihoods.

- Therefore, early action, during the 2020s, will have a correspondingly more beneficial impact on our ability to meet Net Zero targets than later action.

- In June this year the International Energy Agency issued a call to arms on energy innovation, stating that the world “won’t hit climate goals unless energy innovation is rapidly accelerated... About three-quarters of the cumulative reductions in carbon emissions to get on [a path which will meet climate goals] will need to come from technologies that have ‘not yet reached full maturity”[41]. DNV GL expressed this observation in a different way: "Measures today will have a disproportionately higher impact than those in five to ten years’ time”[42].

- Time is of the essence and action during the 2020s is critical.

3.6. Role of and Need for The Project

3.6. Role of and Need for The Project

- Against the backdrop outlined above, the need for and benefits of the Project are manifest and include:

- With the potential to generate an estimated 4.1GW, the Project is a substantial infrastructure asset, capable of delivering huge amounts of low-carbon electricity – enough to power more than 5 million homes each year, starting from as early as 2026.

- The Project would deliver a substantial near-term contribution to decarbonisation, helping to reduce GHG emissions, by offsetting millions of tonnes of CO2 emissions per annum from 2026.

- More than 4.1GW of OWF capacity is required in Scotland and the wider UK to meet policy aims and legal targets for 2030. Any capacity not developed at the Project will need to be made up elsewhere and will not be on stream as quickly (most likely after 2030).

- Decarbonisation is urgent. The scale of and timelines associated with The Project align with that urgency. The 2030 ambition gap will be closed only by bringing forward projects like The Project which connect as much capacity as possible, as early as possible.

- The Project is the only Scottish offshore wind project of significant scale which is proposed to commission between 2025 and 2030 (with the exception of 0.8GW from a recent ScotWind lease winner, currently hoped to commission in 2029).

- The Project can “plug the gap” between Scottish CfD Auction Round 3 (AR3) wind farm developments (coming online in the next three years) and ScotWind developments (which are mostly likely to start to come on stream from the 2030s onwards).

- Development of The Project is well advanced and there is a high degree of certainty attached to its deliverability for a number of reasons including:

– The seabed at The Project is shallower and closer to shore than seabed areas in other proposed OWF locations (e.g. ScotWind);

– The shallow seabed allows for a fixed bottom turbines to be used, a tried and tested foundation solution which can be developed at lower cost than floating technology;

– The seabed at The Project is well surveyed and understood; and

– The established track record of the promoter, SSE, in delivering offshore wind in Scottish and UK waters.

- The Project’s location (shallow waters), design (fixed bottom turbines) and large scale (4.1GW):

– supports UK electricity system adequacy to help meet peak electricity demand, dependability and security of supply requirements; growth in offshore wind capacities, is expected to improve the dependability of those assets as a combined portfolio, and to reduce further any integration costs associated with such growth;

– enables efficiencies and reduce costs, ensuring affordability for the GB consumer

– brings forward an important near-term opportunity for supply chain investment in Scotland

- If developed at its full technically achievable capacity, The Project would provide enough energy to replace 19% of Russian gas imports to the UK. This demonstrates the significant national benefit to energy security provided by a fully developed The Project scheme.

- The Project’s two separate points of connection are also beneficial from both system reinforcement and system operability cost perspectives.

- For all these reasons, The Project is an essential part of the future generation mix. Without The Project, it is probable that delivery of the multitude of policies will fall short, including: the Scotland Sectoral Marine Plan, Scottish Energy Strategy, the Ten Point Plan, UK Net Zero Strategy and UK Offshore Wind Sector Deal, as well as the targets set by the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009, Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019, the (UK) Climate Change Act 2008 (as amended) and the Net Zero Strategy: Build back Greener.

- For all these reasons, The Project is an essential part of the future generation mix. Without The Project, it is probable that delivery of the multitude of policies will fall short, including: the Scotland Sectoral Marine Plan, Scottish Energy Strategy, the Ten Point Plan, UK Net Zero Strategy and UK Offshore Wind Sector Deal, as well as the targets set by the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009, Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019, the (UK) Climate Change Act 2008 (as amended) and the Net Zero Strategy: Build back Greener.

Part B: No Alternative Solutions

Part B: No Alternative Solutions

4. Introduction to the Assessment of Alternatives

4. Introduction to the Assessment of Alternatives

4.1. Overview

4.1. Overview

- This PART B addresses HRA Stage 3A (no alternative solutions). It examines whether there are any feasible alternative solutions to The Project. A range of potential alternatives have been considered. These range from “doing nothing”, to alternative sites, designs, scales and methods of operation.

- The conclusion reached is that there are no feasible alternative solutions to The Project.

- The analysis set out in this Part B is supported by and draws in particular upon the following documents which accompany the Section 36 Consent and Marine Licence applications for the Proposed Development:

- Statement of Need (summarised in Section 3 above)

- Offshore Planning Statement

- Offshore EIA: Project Description (Volume 1 Chapter 3)

- Offshore EIA: Site Selection and Consideration of Alternatives (Volume 1 Chapter 4)

4.2. Approach to Stage 3a: Alternative Solutions

4.2. Approach to Stage 3a: Alternative Solutions

Introduction

- The Habitat Regulations do not define the concept of “no alternative solutions” or the parameters of the exercise, and there is limited case law at the UK and EU level. Therefore, the approach adopted by the Applicant primarily draws upon relevant Scottish (DTA 2021: draft), UK (Defra 2012) and EC guidance (MN 2000 and the EC’s Methodological Guidance) and precedent from previous UK OWF derogation decisions, as detailed further below.

Project Objectives – Step 1

- A consistent theme of guidance[43] and previous OWF derogation planning decisions, is that possible alternative solutions must achieve the core objectives of the Proposed Development.

- In this regard, EC MN 2000 provides [underlining added]: “it is for the competent national authorities to ensure that all feasible alternative solutions that meet the plan/project aims have been explored to the same level of detail.” The EC’s Methodological Guidance reflects MN 2000 and suggests a three step approach for examining the possibility of alternative solutions, the first step being to identify the key objectives of the project in question.

- This approach has also been endorsed by the English High Court in Spurrier[44], which commented as follows [underlining added]:

“Even by itself, the noun "alternative" carries the ordinary, Oxford English Dictionary meaning of "a thing available in place of another", which begs the question what are the relevant objectives or purposes which an alternative would need to serve. However, article 6(4) does not refer simply to the absence of an "alternative" but to an "alternative solution", "alternative" appearing as an adjective, which makes this meaning plain beyond any doubt. In our view, "an alternative" must necessarily be directed at identified objectives or purposes; but it is beyond doubt that "an alternative solution" must be so aimed.”[45]

- This approach was also endorsed by the Court of Appel in R (Plan B Earth) v Secretary of State for Transport[46]:

“Under the Habitats Directive, if a suggested alternative does not meet a central policy objective of the project or plan in issue, then it is no true alternative and will properly be excluded. It is not then, and cannot be, an “alternative solution”. In short, the Habitats Directive has a determining effect on the inclusion or exclusion of alternatives.”

- Defra 2012 similarly states that alternative solutions are “limited to those which would deliver the same overall objective as the original proposal”. In making this point, it uses the example of an OWF:

“For example, in considering alternative solutions to an offshore wind renewable energy development the competent authority need only consider alternative offshore wind renewable energy developments. Alternative forms of energy generation are not alternative solutions to this project as they are beyond the scope of its objective. Similarly, alternative solutions to a port development will be limited to other ways of delivering port capacity, and not other options for importing freight.”[47]

- Defra’s 2021 guidance echoes this advice: “Examples of alternatives that may not meet the original objective include a proposal that…offers nuclear instead of offshore wind energy”.

- Finally, Defra’s 2012 guidance makes the obvious but important point that documents setting out Government policy provide important context for a competent authority when considering the scope of alternative solutions that require to be considered.

- In conclusion, the first step is to identify the core objectives of The Project. These core objectives respond to and must be understood in the context of the policy context and need case which The Project serves, as set out in Section 3 of this Report. It is noted that a similar approach has been followed in all UK OWF HRA derogation cases to date and as illustrated in below.

Do Nothing – Step 2

- A second consistent theme of HRA guidance[48] is that a “do nothing” or “zero option” should be considered, i.e. the outcome of not proceeding with the project at all.

- For example, MN 2000 states: “Crucial is the consideration of the ‘do nothing’ scenario, also known as the ‘zero’ option, which provides the baseline for comparison of alternatives.”[49] DTA 2021 (in draft) similarly suggests it allows a baseline from which to gauge other alternatives and provides a different viewpoint from which to understand the need for the proposal.

- The English courts[50] have cast doubt on the proposition that “do nothing” is a true alternative, though it was recognised by the judge that whether there are IROPI clearly raises the question of whether it is better to do nothing. The do nothing option would fail to achieve any core objectives of a given project and would immediately be discounted where it is clear there are IROPI to proceed with a given project.

- However, for completeness, and given reference to it in pre-existing guidance, the “do nothing” option is considered in this Report. This is consistent with the approach adopted by the SofS in the five UK OWF derogation decisions taken to date.

Identify Feasibile Alternative Solutions – Step 3

- If the “do nothing” option is discounted, the next step is to identify any/ all feasible alternative solutions that meet the core project objectives and would avoid or be materially less damaging for the European site(s) in question, whilst also not resulting in AEOI for another (unaffected) European site.

- Again, all guidance is aligned in indicating that this could (subject to the core project objectives) theoretically include consideration of different location(s), scale(s), design(s) of development or alternative operational processes. However, there are practical limitations to this exercise.

- At this point it is relevant to note that in each of the five previous OWF HRA derogation decisions, the SofS concluded that alternative forms of energy generation would not meet the core objectives for the proposed OWF and that alternatives can consequently be limited to either “do nothing” or “alternative wind farm projects”[51]. This reflects Defra’s 2012 and 2021a guidance and has not been subject to legal challenge, and is therefore adopted in this Report.

- European Court of Justice (ECJ) case law confirms that hypothetical options can be discounted[52]. MN 2000 similarly makes clear that the consideration of alternative solutions should be limited to “feasible” alternative solutions. Defra 2021a helpfully explains that a potential alternative should be: “financially, legally and technically feasible”.

- Guidance does not define or illustrate the boundaries of ‘financial’, ‘legal’ or ‘technical feasibility’. However, logically, a potential alternative would not be feasible if the cost would render the Project unviable or uncompetitive, or if a particular design was considered technically unsound or unsuitable for deployment or would not meet industry safety and regulatory requirements.

- As for legal feasibility, a relevant practical example can be found in the recent UK OWF derogation decisions. By way of example (and in common with the Sof’s earlier decisions), in the HRA for East Anglia ONE North Limited, the SofS concluded as follows:

“The site selection for all offshore wind proposals in the UK is controlled by The Crown Estate leasing process. Sites not within the areas identified by The Crown Estate leasing process or outside of that which the Applicant has secured (the southern East Anglia Zone) are not legally available, and therefore do not represent alternative locations.”

- This suggests that feasible alternative locations can only be within areas/ sites currently identified for leasing either by Crown Estate Scotland (CES) or TCE.

Assessment of Any IdentIfied Alternative Solutions – Step 4

- Finally, MN 2000 guidance advises that where feasible alternative solutions that meet the core project objectives are identified, those alternatives should each be analysed and compared with regard to their relative impact (if any) on any European site(s).

- An assessment of feasible alternative solutions should comprise an assessment of the adverse effects on the specific European site in question, but also any adverse effects on other European sites and qualifying features must be considered.

- At this stage it is not necessarily the case that any feasible alternative that reduces effects on the European site in question results in failure of the alternatives test. Some ECJ case law and EC opinions indicate that the impact of a feasible alternative solution should be materially lower in order for a potential alternative to be considered a genuine alterative[53].

4.3. Content and Structure

4.3. Content and Structure

- Drawing on the guidance and planning precedent identified above, a staged process has been adopted, to provide a structured and sequential method for examination of alternative solutions:

Step 1 | Identify the core project objectives for The Project, in the context of the identified need |

Step 2 | Consider ‘do nothing’ scenario |

Step 3 | Identification of any feasible alternative solutions that meet core project objectives |

Step 4 | Comparative assessment of any feasible alternative solutions on European site(s) |

5. No Alternative Solutions Case: Step 1 – The Core Objectives

5. No Alternative Solutions Case: Step 1 – The Core Objectives

5.1. The Core Objectives of The Project

5.1. The Core Objectives of The Project

- The need for The Project is demonstrated comprehensively in the Statement of Need and has been summarised in Section 3 of this Report. In short, offshore wind must be deployed urgently, starting as soon as possible, and at scale.

- Against this backdrop, the genuine and critical project objectives for The Project are set out in Table 8 Open ▸ below. These six core project objectives respond to the environmental (decarbonisation), regulatory, market and economic factors summarised above.

Table 8 Core project objectives for The Project

6. No Alternative Solutions Case: Step 2 – Do Nothing

6. No Alternative Solutions Case: Step 2 – Do Nothing

- The “do nothing” scenario would comprise not proceeding with The Project and the loss of 4.1GW of offshore wind capacity.

- A “do nothing” scenario would not meet any of The Project core project objectives and can be discounted on that basis.

- If The Project does not proceed, a significant area of seabed identified by TCE as suitable and made available for large-scale offshore wind development in Scottish waters would not be developed in the near-term (if at all).

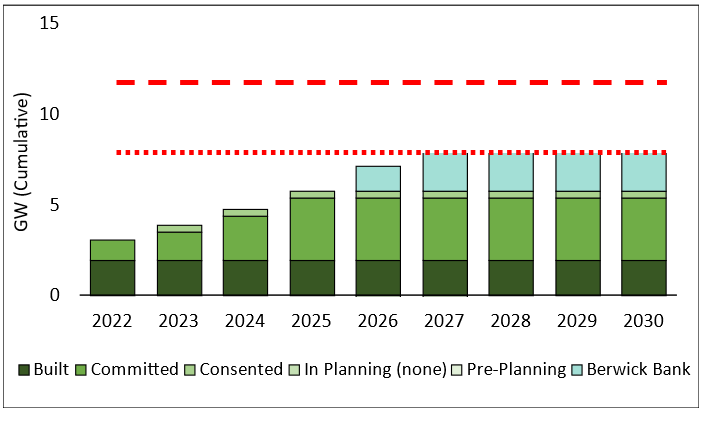

- The Project is the only offshore wind opportunity in Scotland currently listed on the TEC Register as deliverable in the period 2025-2030[55]. Without The Project, Scotland would not increase its installed offshore wind capacity between 2024 (when Moray West is due to commission) and when the ScotWind sites start to commission – see Figure 4[56].

- In the “do nothing” scenario there would be a gap between Scottish AR3 OWFs (coming online in the next three years) and future ScotWind developments (likely to mostly come online in the 2030s).

- In the absence of The Project, Scotland cannot be expected to even meet its lower target of 8GW of offshore wind capacity set in the Offshore Wind Policy Statement. Scottish supply chain opportunities would also be missed.

Figure 4 Current operational and planned future capacities of offshore wind connecting in Scotland, 2021-2030, excluding unsuccessful projects and excluding The Project capacity[57]

- Thus, doing nothing (no Berwick Bank) would substantially hinder decarbonisation and security of supply efforts during the critical 2020s and is to ignore the clear need for rapid OWF deployment at scale. The importance of the decarbonisation, energy security and related affordability challenges mean that no viable OWF projects should be passed over in the development process. It is not compatible with a climate emergency to “do nothing”.

- For all these reasons, the “do nothing” option is discounted.

Table 9 Performance of “Do Nothing” scenario against the Project objectives

7. No Alternative Solutions Case: Step 3 – identify Any Feasible Alternatives

7. No Alternative Solutions Case: Step 3 – identify Any Feasible Alternatives

7.1. Scope of Alternatives Considered

7.1. Scope of Alternatives Considered

- The approach to the identification of feasible alternative solutions in this section is informed by the guidance and previous OWF derogation cases discussed above (Section 4) and the core project objectives for The Project (Section 5).

- The “do nothing” option has been considered and discounted at Step 2 above.

- Consistent with Defra guidance (2012 and 2021a) and the five UK OWF HRA derogation decisions to date, the consideration of feasible alternative solutions is limited to alternative wind farm projects / locations / designs. Alternative (non OWF) forms of energy generation would not meet any of The Project core project objectives and would not support fundamental Scottish and UK Government policy aims as articulated in the Offshore Wind Policy Statement and the BESS, amongst others.

- Therefore, the scope for consideration of potentially feasible alternative solutions is as follows:

- Alternative OFW array locations:

– Alternative array locations not in the UK Renewable Energy Zone (REZ);

– Alternative array locations within the UK REZ, excluding the former Firth of Forth Zone;

– Alternative array locations within the former Firth of Forth Zone.

- Alternative design and modes of operation:

– Alternative scale: developable array area, within constraints of the Firth of Forth Zone;

– Alternative design: turbines and layout and minimum lower tip height.

- Each of the above is considered in turn below, in the context of The Project core project objectives, and with regards to their feasibility (financial, legal and technical).

7.2. Alternative Array Locations not in the UK REZ

7.2. Alternative Array Locations not in the UK REZ

- Scotland and the UK have legal obligations in relation to carbon emission reductions to achieve Net Zero, and corresponding policy aims in respect of the deployment of renewable energy generation and energy security. Conversely, other international and EU countries similarly have their own emission reduction and renewable energy targets and security of energy supply aims.