Part B: No Alternative Solutions

4. Introduction to the Assessment of Alternatives

4.1. Overview

- This PART B addresses HRA Stage 3A (no alternative solutions). It examines whether there are any feasible alternative solutions to The Project. A range of potential alternatives have been considered. These range from “doing nothing”, to alternative sites, designs, scales and methods of operation.

- The conclusion reached is that there are no feasible alternative solutions to The Project.

- The analysis set out in this Part B is supported by and draws in particular upon the following documents which accompany the Section 36 Consent and Marine Licence applications for the Proposed Development:

- Statement of Need (summarised in Section 3 above)

- Offshore Planning Statement

- Offshore EIA: Project Description (Volume 1 Chapter 3)

- Offshore EIA: Site Selection and Consideration of Alternatives (Volume 1 Chapter 4)

4.2. Approach to Stage 3a: Alternative Solutions

Introduction

- The Habitat Regulations do not define the concept of “no alternative solutions” or the parameters of the exercise, and there is limited case law at the UK and EU level. Therefore, the approach adopted by the Applicant primarily draws upon relevant Scottish (DTA 2021: draft), UK (Defra 2012) and EC guidance (MN 2000 and the EC’s Methodological Guidance) and precedent from previous UK OWF derogation decisions, as detailed further below.

Project Objectives – Step 1

- A consistent theme of guidance[43] and previous OWF derogation planning decisions, is that possible alternative solutions must achieve the core objectives of the Proposed Development.

- In this regard, EC MN 2000 provides [underlining added]: “it is for the competent national authorities to ensure that all feasible alternative solutions that meet the plan/project aims have been explored to the same level of detail.” The EC’s Methodological Guidance reflects MN 2000 and suggests a three step approach for examining the possibility of alternative solutions, the first step being to identify the key objectives of the project in question.

- This approach has also been endorsed by the English High Court in Spurrier[44], which commented as follows [underlining added]:

“Even by itself, the noun "alternative" carries the ordinary, Oxford English Dictionary meaning of "a thing available in place of another", which begs the question what are the relevant objectives or purposes which an alternative would need to serve. However, article 6(4) does not refer simply to the absence of an "alternative" but to an "alternative solution", "alternative" appearing as an adjective, which makes this meaning plain beyond any doubt. In our view, "an alternative" must necessarily be directed at identified objectives or purposes; but it is beyond doubt that "an alternative solution" must be so aimed.”[45]

- This approach was also endorsed by the Court of Appel in R (Plan B Earth) v Secretary of State for Transport[46]:

“Under the Habitats Directive, if a suggested alternative does not meet a central policy objective of the project or plan in issue, then it is no true alternative and will properly be excluded. It is not then, and cannot be, an “alternative solution”. In short, the Habitats Directive has a determining effect on the inclusion or exclusion of alternatives.”

- Defra 2012 similarly states that alternative solutions are “limited to those which would deliver the same overall objective as the original proposal”. In making this point, it uses the example of an OWF:

“For example, in considering alternative solutions to an offshore wind renewable energy development the competent authority need only consider alternative offshore wind renewable energy developments. Alternative forms of energy generation are not alternative solutions to this project as they are beyond the scope of its objective. Similarly, alternative solutions to a port development will be limited to other ways of delivering port capacity, and not other options for importing freight.”[47]

- Defra’s 2021 guidance echoes this advice: “Examples of alternatives that may not meet the original objective include a proposal that…offers nuclear instead of offshore wind energy”.

- Finally, Defra’s 2012 guidance makes the obvious but important point that documents setting out Government policy provide important context for a competent authority when considering the scope of alternative solutions that require to be considered.

- In conclusion, the first step is to identify the core objectives of The Project. These core objectives respond to and must be understood in the context of the policy context and need case which The Project serves, as set out in Section 3 of this Report. It is noted that a similar approach has been followed in all UK OWF HRA derogation cases to date and as illustrated in below.

Do Nothing – Step 2

- A second consistent theme of HRA guidance[48] is that a “do nothing” or “zero option” should be considered, i.e. the outcome of not proceeding with the project at all.

- For example, MN 2000 states: “Crucial is the consideration of the ‘do nothing’ scenario, also known as the ‘zero’ option, which provides the baseline for comparison of alternatives.”[49] DTA 2021 (in draft) similarly suggests it allows a baseline from which to gauge other alternatives and provides a different viewpoint from which to understand the need for the proposal.

- The English courts[50] have cast doubt on the proposition that “do nothing” is a true alternative, though it was recognised by the judge that whether there are IROPI clearly raises the question of whether it is better to do nothing. The do nothing option would fail to achieve any core objectives of a given project and would immediately be discounted where it is clear there are IROPI to proceed with a given project.

- However, for completeness, and given reference to it in pre-existing guidance, the “do nothing” option is considered in this Report. This is consistent with the approach adopted by the SofS in the five UK OWF derogation decisions taken to date.

Identify Feasibile Alternative Solutions – Step 3

- If the “do nothing” option is discounted, the next step is to identify any/ all feasible alternative solutions that meet the core project objectives and would avoid or be materially less damaging for the European site(s) in question, whilst also not resulting in AEOI for another (unaffected) European site.

- Again, all guidance is aligned in indicating that this could (subject to the core project objectives) theoretically include consideration of different location(s), scale(s), design(s) of development or alternative operational processes. However, there are practical limitations to this exercise.

- At this point it is relevant to note that in each of the five previous OWF HRA derogation decisions, the SofS concluded that alternative forms of energy generation would not meet the core objectives for the proposed OWF and that alternatives can consequently be limited to either “do nothing” or “alternative wind farm projects”[51]. This reflects Defra’s 2012 and 2021a guidance and has not been subject to legal challenge, and is therefore adopted in this Report.

- European Court of Justice (ECJ) case law confirms that hypothetical options can be discounted[52]. MN 2000 similarly makes clear that the consideration of alternative solutions should be limited to “feasible” alternative solutions. Defra 2021a helpfully explains that a potential alternative should be: “financially, legally and technically feasible”.

- Guidance does not define or illustrate the boundaries of ‘financial’, ‘legal’ or ‘technical feasibility’. However, logically, a potential alternative would not be feasible if the cost would render the Project unviable or uncompetitive, or if a particular design was considered technically unsound or unsuitable for deployment or would not meet industry safety and regulatory requirements.

- As for legal feasibility, a relevant practical example can be found in the recent UK OWF derogation decisions. By way of example (and in common with the Sof’s earlier decisions), in the HRA for East Anglia ONE North Limited, the SofS concluded as follows:

“The site selection for all offshore wind proposals in the UK is controlled by The Crown Estate leasing process. Sites not within the areas identified by The Crown Estate leasing process or outside of that which the Applicant has secured (the southern East Anglia Zone) are not legally available, and therefore do not represent alternative locations.”

- This suggests that feasible alternative locations can only be within areas/ sites currently identified for leasing either by Crown Estate Scotland (CES) or TCE.

Assessment of Any IdentIfied Alternative Solutions – Step 4

- Finally, MN 2000 guidance advises that where feasible alternative solutions that meet the core project objectives are identified, those alternatives should each be analysed and compared with regard to their relative impact (if any) on any European site(s).

- An assessment of feasible alternative solutions should comprise an assessment of the adverse effects on the specific European site in question, but also any adverse effects on other European sites and qualifying features must be considered.

- At this stage it is not necessarily the case that any feasible alternative that reduces effects on the European site in question results in failure of the alternatives test. Some ECJ case law and EC opinions indicate that the impact of a feasible alternative solution should be materially lower in order for a potential alternative to be considered a genuine alterative[53].

4.3. Content and Structure

- Drawing on the guidance and planning precedent identified above, a staged process has been adopted, to provide a structured and sequential method for examination of alternative solutions:

Step 1 | Identify the core project objectives for The Project, in the context of the identified need |

Step 2 | Consider ‘do nothing’ scenario |

Step 3 | Identification of any feasible alternative solutions that meet core project objectives |

Step 4 | Comparative assessment of any feasible alternative solutions on European site(s) |

5. No Alternative Solutions Case: Step 1 – The Core Objectives

5.1. The Core Objectives of The Project

- The need for The Project is demonstrated comprehensively in the Statement of Need and has been summarised in Section 3 of this Report. In short, offshore wind must be deployed urgently, starting as soon as possible, and at scale.

- Against this backdrop, the genuine and critical project objectives for The Project are set out in Table 8 Open ▸ below. These six core project objectives respond to the environmental (decarbonisation), regulatory, market and economic factors summarised above.

Table 8 Core project objectives for The Project

6. No Alternative Solutions Case: Step 2 – Do Nothing

- The “do nothing” scenario would comprise not proceeding with The Project and the loss of 4.1GW of offshore wind capacity.

- A “do nothing” scenario would not meet any of The Project core project objectives and can be discounted on that basis.

- If The Project does not proceed, a significant area of seabed identified by TCE as suitable and made available for large-scale offshore wind development in Scottish waters would not be developed in the near-term (if at all).

- The Project is the only offshore wind opportunity in Scotland currently listed on the TEC Register as deliverable in the period 2025-2030[55]. Without The Project, Scotland would not increase its installed offshore wind capacity between 2024 (when Moray West is due to commission) and when the ScotWind sites start to commission – see Figure 4[56].

- In the “do nothing” scenario there would be a gap between Scottish AR3 OWFs (coming online in the next three years) and future ScotWind developments (likely to mostly come online in the 2030s).

- In the absence of The Project, Scotland cannot be expected to even meet its lower target of 8GW of offshore wind capacity set in the Offshore Wind Policy Statement. Scottish supply chain opportunities would also be missed.

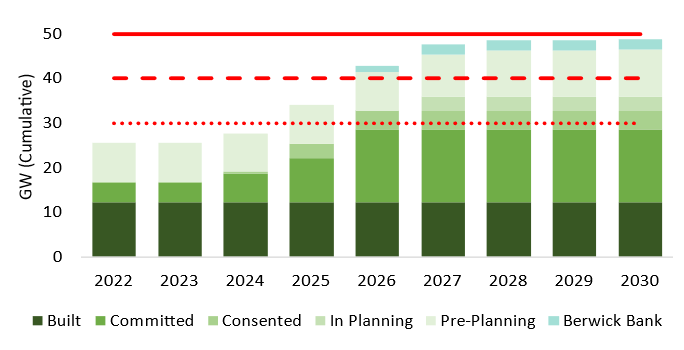

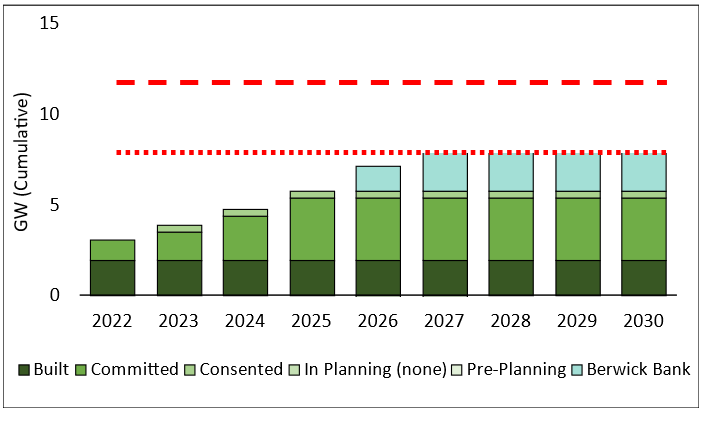

Figure 4 Current operational and planned future capacities of offshore wind connecting in Scotland, 2021-2030, excluding unsuccessful projects and excluding The Project capacity[57]

- Thus, doing nothing (no Berwick Bank) would substantially hinder decarbonisation and security of supply efforts during the critical 2020s and is to ignore the clear need for rapid OWF deployment at scale. The importance of the decarbonisation, energy security and related affordability challenges mean that no viable OWF projects should be passed over in the development process. It is not compatible with a climate emergency to “do nothing”.

- For all these reasons, the “do nothing” option is discounted.

Table 9 Performance of “Do Nothing” scenario against the Project objectives

7. No Alternative Solutions Case: Step 3 – identify Any Feasible Alternatives

7.1. Scope of Alternatives Considered

- The approach to the identification of feasible alternative solutions in this section is informed by the guidance and previous OWF derogation cases discussed above (Section 4) and the core project objectives for The Project (Section 5).

- The “do nothing” option has been considered and discounted at Step 2 above.

- Consistent with Defra guidance (2012 and 2021a) and the five UK OWF HRA derogation decisions to date, the consideration of feasible alternative solutions is limited to alternative wind farm projects / locations / designs. Alternative (non OWF) forms of energy generation would not meet any of The Project core project objectives and would not support fundamental Scottish and UK Government policy aims as articulated in the Offshore Wind Policy Statement and the BESS, amongst others.

- Therefore, the scope for consideration of potentially feasible alternative solutions is as follows:

- Alternative OFW array locations:

– Alternative array locations not in the UK Renewable Energy Zone (REZ);

– Alternative array locations within the UK REZ, excluding the former Firth of Forth Zone;

– Alternative array locations within the former Firth of Forth Zone.

- Alternative design and modes of operation:

– Alternative scale: developable array area, within constraints of the Firth of Forth Zone;

– Alternative design: turbines and layout and minimum lower tip height.

- Each of the above is considered in turn below, in the context of The Project core project objectives, and with regards to their feasibility (financial, legal and technical).

7.2. Alternative Array Locations not in the UK REZ

- Scotland and the UK have legal obligations in relation to carbon emission reductions to achieve Net Zero, and corresponding policy aims in respect of the deployment of renewable energy generation and energy security. Conversely, other international and EU countries similarly have their own emission reduction and renewable energy targets and security of energy supply aims.

- Sites outside the UK REZ have not been claimed by the UK under the Energy Act 2004 for exploitation for energy production, are not subject to TCE/CES offshore wind leasing rounds and are not available to the Applicant. Moreover, such sites are required for other EU member states and countries to achieve their own respective targets pursuant to the Paris Agreement in respect of climate change and renewable energy, and to ensure their own security of energy supply. Therefore, it is considered unlikely any such site would be made available for an OWF to connect to the GB network.

- For the above reasons alternative sites for OWFs outside UK REZ would provide no contribution to:

- Scottish and UK interim emission reduction targets (2030) or the 2045/50 Net Zero targets

- Scotland’s target of 8 – 11GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030

- The UK target for 50GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030

- Energy security of supply in Scotland and the UK

- This alternative would also fail to meet any of The Project core project objectives as set out in Table 10 Open ▸ below.

- It is therefore concluded that locations outside the UK REZ cannot reasonably be considered a feasible alternative solution to The Project.

- It is noted that a similar conclusion was reached by the SofS in each of the five previous UK OWF HRA derogation cases. For example, the SofS’s HRA for East Anglia ONE North states[58]:

“Although the UK is party to international treaties and conventions in relation to climate change and renewable energy, according to the principle of subsidiarity and its legally binding commitments under those treaties and conventions, the UK has its own specific legal obligations and targets in relation to carbon emission reductions and renewable energy generation. Other international and EU countries similarly have their own (different) binding targets. Sites outside the UK are required for other countries to achieve their own respective targets in respect of climate change and renewable energy.”

Table 10 Performance of alternative array locations not in the UK REZ against the Project objectives

7.3. Alternative Array Locations Outside the Former Firth of Forth Zone

Overview

- This section considers the potential for alternative array sites in Scottish waters and the wider UK REZ, excluding the former Firth of Forth Zone (in which The Proposed Development is located).

- The potential for alternative array locations within the former Firth of Forth Zone is considered separately in Section 7.4 of this Report.

Legal Feasibility – Available Sites

- TCE and CES own or exercise exclusive rights to manage the leasing of and exploitation of the seabed for offshore wind development within UK territorial waters and, through the Energy Act 2004, the wider UK REZ. TCE / CES make areas of seabed available for offshore wind development selectively in successive offshore leasing rounds, usually several years apart.

- As noted earlier, in recent OWF HRA derogation decisions the SofS has concluded that sites outside of areas secured by the respective applicant do not represent alternative locations. For example, again taking the HRA for East Anglia ONE North as an example[59]:

“The site selection for all offshore wind proposals in the UK is controlled by The Crown Estate leasing process. Sites not within the areas identified by The Crown Estate leasing process or outside of that which the Applicant has secured (the southern East Anglia Zone) are not legally available, and therefore do not represent alternative locations.”

- Outside of ScotWind (addressed further below), other areas of seabed are not available to the Applicant and are not feasible alternative solutions on that basis. However, there are many additional reasons to discount other locations / leasing rounds as alternatives, as set out in the following sections.

Future Offshore Wind Leasing Rounds

- CES has recently concluded the ScotWind leasing round and is focused on the Innovation and Targeted Oil and Gas Decarbonisation (INTOG) leasing round (both discussed further below). TCE is currently planning the Celtic Sea leasing round (also discussed below).

- Outside of Celtic Sea and INTOG, any future alternative array location to replace The Proposed Development would depend on a fresh site leasing process being initiated by TCE and CES. There is no sign of that in the short term.

- When and where (or indeed if) any further areas of the seabed may be offered by either CES or TCE is unknown and a matter of speculation. At this stage, the availability of alternative locations outside of current TCE / CES leasing rounds is theoretical[60] (as well as legal unavailable – see above) and can be discounted on that basis. Therefore, any parts of the UK REZ not currently the subject of an OWF leasing round do not constitute feasible alternative solutions.

- Future locations released via future OWF leasing rounds can additionally be discounted on timing grounds. Figure 5 below is indicative and reflective of historic and not necessarily future OWF development timescales. However, areas of seabed developed to date were identified as areas of least constraint / greatest opportunity for OWF, and there is no reason to automatically assume any future sites would be less challenging or can be more rapidly developed than previously, or that it will be possible to do so while avoiding any adverse effects on European sites.

Figure 5 Indicative historic time frames for delivering OWF Projects (Source TCE).

- Even if the highly optimistic assumption is made that historic timescales could be condensed by as much as 50%[61], a fresh OWF leasing round starting in 2023 would not deliver substantial additional installed OWF capacity before 2030. Moreover, as discussed further below and in the Applicant’s Statement of Need, grid connection dates for OWF projects in development now (e.g. ScotWind) are typically from 2033 onwards.

- The huge scale of Scotland and UK targets for offshore wind, the short timescales now to meet 2030 targets (7 years) and prevalence of offshore environmental and technical constraints, mean that lost capacity (at the scale of 4.1GW) cannot be expected to be offset by other future uninitiated leasing rounds, even on the most optimistic of outlooks.

- For the reasons set out above, it is concluded that alternative locations outside areas/ sites currently identified for leasing either by CES or TCE are not alternative solutions.

ACTIVE CROWN ESTATE OWF LEASING ROUNDS - OVERVIEW

- CES and TCE leasing rounds completed or underway are summarised in Table 11 Open ▸ and further detailed in the subsequent sections, where relevant. The Proposed Development is located within the former Firth of Forth Zone, a region identified and made available by TCE during Round 3.

Table 11 Offshore wind leasing rounds in Scotland and the UK

- Operational/ existing OWF projects from Rounds 1, 2 and 3, the TCE Extensions Round (2010) and the STW round have already been fully or largely developed and form part of existing baseline of OWF installed capacity and do not provide additional installed capacity (as an alternative to The Project) that is required to achieve current Scottish and UK OWF capacity targets of 11GW and 50GW respectively. Accordingly, they can be discounted as alternatives to The Project.

- Figure 6 and Figure 7 below taken from the Applicant’s Statement of Need illustrate current Scottish (Figure 6) and UK (Figure 7) operational and consented capacity, and the predicted trajectory up to 2030 based on the TEC Register. The red dotted line indicates the Scottish Government’s lower target of 8GW of offshore wind capacity and the red dashed line indicates the upper 11GW target.

- TCE Project Listings lists 1.9GW of built offshore wind in Scotland, with a further 3.9GW of consented and/or committed projects which are currently scheduled to deliver before 2025. These projects include Neart na Gaoithe (0.4GW), Seagreen Phase 1 (1.1GW), Inch Cape (1.1GW), Moray West (0.9GW) and Seagreen Phase 1A (0.4GW).

- No other offshore wind farms are yet consented in Scottish waters, and none are currently listed as in the planning process in TCE’s project listings. The Project is the only Scottish OWF with seabed rights, in planning and with a grid connection agreement connecting substantial capacity before 2030 (2.3GW).

- There is 3.7GW of ScotWind sites listed with grid connection agreements however none of them are effective before 2033. While some ScotWind projects aim to be advanced in the late 2020s, challenges clearly remain in securing National Grid connection agreements which could result in delays to some projects. Due to the uncertainty around National Grid connection options and potential supply chain issues it is likely that projects leased through the Scotwind project could have varied timelines for project development. As a result, it is hard to predict how many projects will contribute to 2030 targets with a number of projects likely to come online in the following decade.

- To meet Scotland's Offshore Wind installed capacity target, between 8 and 11GW of offshore wind must be commissioned before 2030. As shown on Figure 7 above, in the absence of The Project, Scotland will not meet its lower target of 8GW of offshore wind capacity (red dotted line), and the 11GW target (red dashed line) is unachievable unless other project timelines are brought forwards ahead of their current grid connection dates.

- Only by consenting the Project can Scotland be sure to meet the 8GW lower target threshold by 2030 and maintain the necessary trajectory towards the 11GW target.

- The picture in terms of the need for The Project to achieve OWF installed capacity targets (50GW by 2030) is the same at UK level. TCE Project Listings includes 12.3GW of built offshore wind in the UK, with a further 8GW under construction. These include Dogger Bank (3.6GW), Hornsea 2 (1.4GW), Sofia (1.4GW) and Neart na Gaoithe and Seagreen Phase 1 (0.4GW and 1.1GW respectively) in Scotland. Hornsea 2 is currently commissioning therefore partially operational.

- An additional 12.4GW of capacity has been consented but is not yet under construction. These projects are currently scheduled to deliver before the end of 2030, and include the Scottish projects listed above. Other projects include Hornsea Project Three (3GW), East Anglia Three (1.5GW), Norfolk Boreas (1.8GW), Norfolk Vanguard (1.8GW), East Anglia One North and East Anglia Two (each 1GW)

- UK installed and operational capacity from already consented projects has the potential to be 32.7GW by the end of 2030, subject to all currently indicated capacity being fully delivered at the current grid connection date. TCE’s Project Listing also includes 3.4GW of projects currently in planning (including Awel y Môr and Hornsea 4).

- The total pipeline of projects with seabed leases which have not yet formally entered planning, consists of 33 projects with 44.1GW of potential capacity. Grid connection dates for these projects, apart from The Project, are largely scheduled for the 2030s. The projects cover a range of technologies, including extensions to existing (operational) seafloor mounted offshore wind farms, for example Rampion and Dudgeon[64].

- Figure 7 below accordingly shows that The Project also has a critical role to play in achieving the UK's 2030 target capacity of 50GW (solid red line).

- Figure 7 taken from the Applicant’s Statement of Need shows the cumulative operational capacity of offshore wind in the UK assuming all projects currently listed are delivered consistent with their current connection dates and capacities.

- It illustrates that, to achieve the BESS target of 50GW by 2030, requires all projects currently in planning, including The Project, to be delivered according to their current connection dates and requires some other pipeline projects (e.g. ScotWind) to be accelerated and brought forwards into the 2020s.

- However, as set out in the Applicant’s Statement of Need, analysis of original estimated installed capacity at the point of lease grant, compared to TCE data on delivered capacity, shows that historically, the attrition rate for UK OWF projects has been around 30%[65]. For some OWF leasing rounds the attrition rate has been even higher (e.g. Scottish Territorial Waters round). The inclusion of a project on a future project pipeline does not indicate that the project will go ahead, or if it does, at a particular generation capacity; attrition occurs for various reasons, including the consenting process, financial reasons, construction reasons or supply chain issues. A 100% success rate for future new projects is neither a reasonable nor a safe assumption.

- Without The Project the 2030 targets at Scottish and UK level will therefore not be met. Any suggestion that other OWF projects could make up for the loss of a single 4.1GW project fundamentally misunderstands the scale of the task to make substantial progress by 2030. Other OWF projects either provide part of the existing baseline of installed capacity or are part of a future pipeline of projects all of which is required.

- Accordingly, it is concluded that other projects are needed in addition to, not instead of, The Project. Other OWF projects are not alternative solutions to The Project.

- For completeness, further commentary on and justification for discounting other current OWF leasing rounds is provided in the following sections.

TCE Extension Round 2017

- Seven extension sites in English and Welsh waters were awarded in 2017 with a total combined of capacity of 2.85GW. The following observations are made:

- It would be necessary for all seven extension projects to be delivered to their maximum anticipated capacity to offset just ~60% of the capacity lost if The Project did not proceed.

- The purpose of the extension projects is to provide additional capacity towards the UK’s 50GW target, not make up a "capacity gap" created by a failure to deliver remaining Round 3 projects.

- TCE Extensions Round (2017) projects will not contribute to Scotland’s domestic decarbonisation targets (and would only partially achieve The Project core project objective 1).

- TCE Extension Round (2017) projects would not achieve The Project core project objective 3 (efficient use of very limited seabed available for fixed foundation OWFs in Scottish waters).

- It has been concluded in previous Sections of this Report that “do nothing” (i.e. no The Project) is not an alternative solution and that Scottish and UK OWF capacity targets for 2030 will not be met without The Project’s contribution. The existence of the TCE Extensions Round (2017) does not alter that conclusion.

- For all these reasons, reliance on TCE Extensions Round (2017) projects (alone or in aggregate) is not an alternative solution to The Project.

Round 4 Sites

- Six Round 4 projects in English and Welsh waters were selected in February 2021 with a total estimated combined capacity of 7,980MW. Five of the six projects have proposed total capacities of 1,500MW, with the remainder proposing a total capacity of 480MW[66]. In August 2022, following completion of the plan-level HRA process TCE indicated it would be moving forwards to conclude Agreements for Lease.

- The following observations are made:

- The Applicant does not hold any development rights in any Round 4 sites. None of the Round 4 sites are available to the Applicant.

- Even assuming improvement on historic OWF development timescales (see Figure 6 above), these projects are unlikely to be generating power before 2030.

- With one exception, the projected dates for connection of Round 4 projects on the National Grid’s Transmission Entry Capacity (TEC) Register are all post 2030. The one project with grid connection agreement before 2030 (Eastern Regions, 1.5 GW) would not offset the lost capacity if The Project did not proceed.

- The maximum individual project size is set at 1.5GW and no individual project progressed via Round 4 would make the same contribution as The Project.

- The purpose of the Round 4 projects is to provide additional capacity towards the UK’s 50GW target, not make up a "capacity gap" created by a failure to deliver remaining Round 3 projects such as The Project.

- Round 4 projects will not contribute to Scotland’s domestic decarbonisation targets (and would only partially achieve The Project core project objective 1).

- Round 4 projects do not achieve The Project core project objective 3 (efficient use of very limited seabed available for fixed foundation OWFs in Scottish waters).

- It has been concluded above that “do nothing” (i.e. no The Project) is not an alternative solution and that Scottish and UK OWF capacity targets for 2030 will not be met without The Project’s contribution. The existence of the Round 4 does not alter that conclusion.

- For all these reasons, it is concluded that reliance on Round 4 projects (alone or in aggregate) is not an alternative solution to The Project.

Celtic Sea Floating Offshore Wind Farm Round

- TCE is currently planning a leasing round for floating wind projects in the Celtic Sea. The Celtic Sea round is intended to provide up to 4GW of floating wind energy capacity by 2035[67]. Eligible projects must be between 300MW (minimum) and 1GW (maximum) and must be located within one of five (refined) areas of search identified by TCE.

- The latest update from TCE (October 2022) indicates that an Information Memorandum will be published in spring 2023 ahead of formal launch of the three-stage tender process in mid-2023, with a view to awarding Agreements for Lease by the end of 2023.

- The following observations are made:

- The timescales for the leasing round may slip backwards, and/or areas of search may change (e.g. the plan-level HRA process for Celtic Sea is ongoing in parallel and could lead to changes or delays) which may alter the scale and nature of the opportunity.

- TCE’s stated aspiration is for build out of the successful projects to occur in the period 2030 – 2035. Therefore, it does not appear to be intended (and is unlikely in any event) that the Celtic Sea round will provide any substantial contribution to the 2030 targets.

- Even assuming improvement on historic OWF development timescales (see Figure 6 above, which largely relate to fixed bottom OWF, not floating), these projects are unlikely to be generating power before 2030.

- Connecting these projects to the grid will depend on the outcome of phase 2 of the Holistic Network Design (HND) process, with connection dates highly likely from 2030 onwards.

- Given the above, Celtic Sea round projects will not achieve The Project core project objective 5 (deliver a significant volume of new low carbon electricity generation as soon as possible, with a substantial contribution to the UK national grid before 2030) nor core project objective 6 (helping ensure the UK energy supply security from the mid-2020s).

- The maximum individual project size is set at 1GW and no individual project progressed via the Celtic Sea round would make the same contribution as The Project.

- It would be necessary for the full 4GW target to be delivered to offset the majority of the capacity lost if The Project did not proceed.

- The purpose of the projects is to provide additional floating capacity towards the UK’s 50GW target, not make up a "capacity gap" created by the loss of remaining Round 3 projects such as The Project or Round 4 projects

- Given their location (outside Scottish waters) and the aim to accelerate commercial scale floating offshore wind, Celtic Sea projects would not achieve The Project core project objective 3 (efficient use of very limited seabed available for fixed foundation OWFs in Scottish waters).

- Fixed bottom offshore wind deployed this decade (such as The Project) is likely to be significantly cheaper over its lifetime than floating offshore wind deployed over the coming twenty years (see comparative analysis in section 8.4 of the Applicant’s Statement of Need). Celtic Sea projects would not achieve The Project core project objective 4 (deliver low carbon electricity at the lowest possible cost to the consumer).

- Celtic Sea projects will not contribute to Scotland’s domestic decarbonisation targets (and would only partially achieve The Project core project objective 1).

- It has been concluded above that “do nothing” (i.e. no The Project) is not an alternative solution and that Scottish and UK OWF capacity targets will not be met without The Project’s contribution. The existence of the Celtic Sea round does not alter that conclusion.

- For all these reasons, reliance on Celtic Sea Round projects (alone or in aggregate) is not an alternative solution to The Project.

INTOG

- The INTOG lease round has recently been set up to allow future OWFs to provide low carbon electricity to power oil and gas installations as well as alternative outputs such as hydrogen. Two types/scales of project are envisaged by CES[68]:

- “IN” – small scale projects of less than 100 MW; and

- “TOG” - Projects connected directly to oil and gas infrastructure, to provide electricity and reduce the carbon emissions associated with production.

- CES has set a maximum aggregate capacity limit that can be awarded exclusivity of 5.7GW for TOG projects and 500MW for Innovation projects[69]. Therefore, the overall capacity of the INTOG leasing round is currently expected to be 6.2GW.

- The application window for INTOG closed on 18 November 2022. CES has estimated that the evaluation of submitted applications will take around 3 months, with exclusivity agreements entered with successful bidders in late February/early March 2023.

- The following observations are made:

- It is understood that the Sectoral Marine Plan for Offshore Wind is under review and is to be updated to identify Plan Option areas for INTOG projects. Therefore, at this stage, there remains a risk of delay and spatial planning uncertainty/ risk.

- CES has indicated Option Agreements will only be signed with successful bidders after the Sectoral Marine Plan update is complete, which is not expected until winter 2023/2024. Therefore, significant development work on these projects may not commence until 2024 or later.

- Even assuming improvement on historic OWF development timescales (see Figure 6 above, which largely relate to fixed bottom OWF, not floating), these projects are unlikely to be generating power at scale before 2030.

- It is expected that TOG projects will connect to an off-grid solution (i.e., an oil and gas installation), to facilitate the North Sea energy transition. Thus, these projects would not be exporting power to the UK national grid.

- In view of all the above, INTOG Round projects will not achieve The Project core project objective 5 (deliver a significant volume of new low carbon electricity generation as soon as possible, with a substantial contribution to the UK national grid before 2030) nor core project objective 6 (helping ensure the UK energy supply security from the mid-2020s).

- It would be necessary for around 65% of the INTOG Round projects to be delivered to the maximum capacity to offset the capacity lost if The Project did not proceed. As mentioned above, historic data shows an average attrition rate of approximately 30% of OWF rounds.

- Due to the greater distance from shore and bathymetry / deeper water depths, floating offshore wind turbines are likely to be the primary technology. As such INTOG projects would not achieve The Project core project objective 3 (efficient use of very limited seabed available for fixed foundation OWFs in Scottish waters).

- Fixed bottom offshore wind deployed this decade (such as The Project) is likely to be significantly cheaper over its lifetime than floating offshore wind deployed over the coming twenty years (see comparative analysis in section 8.4 of the Applicant’s Statement of Need). INTOG projects would not achieve The Project core project objective 4 (deliver low carbon electricity at the lowest possible cost to the consumer).

- It has been concluded above that “do nothing” (i.e. no Project) is not an alternative solution and that Scottish and UK OWF capacity targets will not be met without The Project’s contribution. The existence of the INTOG round does not alter that conclusion.

- For all these reasons, reliance on the INTOG Round projects (alone or in aggregate) is not an alternative solution to The Project.