Pre-eradication Field Studies

- Key species monitoring and field studies would be undertaken prior to, during and after the proposed eradication. Monitoring would commence in the spring and summer ahead of a winter eradication to enable baseline information to be collected, this is outlined in the monitoring section below. This monitoring would continue for two years after the eradication phase. A detailed Evaluation and Monitoring Plan would be prepared to ensure relevant, robust, and accurate data collection procedures, data storage and analysis. Further information on the approach to monitoring and reporting is discussed below.

- Seabird habitat field measurements (ledge dimensions, soils structures etc.), testing for positioning of anchor stations for rope access, and a seabird census would be undertaken with a full colony baseline count using recognised methods as detailed in Walsh et al (1995), including photographic records and digital mapping.

- It is also important to assess the level of native predators (i.e. raptors and gulls) on Inchcolm to determine what effect these species may have on the recovery and spread of seabirds on the island. There are few native predators on Inchcolm, although gulls and raptors are known to predate other bird species. Gull numbers are unlikely to change due to rats being eradicated from the island, as they are not significantly affected by rat predation.

Biosecurity Plan

- Once black rats were successfully eradicated from Inchcolm, the priority would be to ensure that they, or brown rats, do not become re-established on the island. As such, an effective Biosecurity Plan would be developed and fully implemented prior to the eradication phase of the programme.

- Biosecurity measures need to be put in place to ensure the rodent-free status is maintained. Biosecurity planning involves the identification of risk species and potential ‘pathways’, such as boats, helicopters, visitors, lighthouse boards and construction work. Prevention measures are required to ensure that invasive species are not transported via these potential pathways. The Biosecurity Plan would be developed together with input from HES who manage Inchcolm as well as vessel operators who bring tourists to the island.

- The Biosecurity Plan would be based on the approach and measures set out by Biodiversity for LIFE and will provide details to minimise the risk of accidental liberation of rodents, and what measures should be taken if a rodent is sighted on the island. If rats were detected on Inchcolm within two years, it would be important to be able to distinguish between the failure of the eradication and a biosecurity failure. DNA samples of black rats from Inchcolm and other locations across the UK, and brown rats from nearby islands and the mainland would be collected and stored in advance of eradication. Trapping of rats and the use of trail cameras would be important to determine the species to confirm eradication failure or incursion.

- The greatest risk of reinvasion is from the mainland. Rodents can be accidentally transported by a number of means, such as local charter boat movements, visiting tourists, visiting researchers and private yachts visiting Inchcolm. The Biosecurity Plan would ensure these visiting vessels are advised of the rat-free status of Inchcolm, through the Communication and Engagement Strategy, and asked to maintain vigilance. Quarantine practices from other islands (such as St Kilda, Lundy Island, Isle of Canna, St Agnes and Gugh, Shiants), for example may be able to be adapted for use on Inchcolm.

- As Inchcolm is within swimming range of brown rats, biosecurity needs to be maintained for the operational lifetime of the Proposed Development. It would be important to educate local HES staff or any other relevant agencies and stakeholders as well as the landowner to ensure that the biosecurity can continue to be implemented by these groups in the long-term, with support of a Biosecurity Warden/qualified contractor where appropriate. Data collection and management is important (particularly if incursions are detected and subsequently eradicated); all sightings and other rodent-related observations would be recorded and investigated.

- As part of the Biosecurity Plan an Incursion Response Plan would be prepared which would come into force should the reoccurrence of rodents be detected. The quicker the response, the easier it is likely to be to initiate further removal and for this to be successful as only a few animals may be involved (Thomas & Varnham 2016).

- It should be noted the Applicant will fund the preparation of the biosecurity plan and incursion response plan, as well as the continued implementation of associated biosecurity and incursion response measures.

Eradication and Intensive Monitoring

- The proposals within this section provide an outline of the currently proposed approaches to eradication and monitoring. These approaches will be confirmed and agreed with stakeholders when preparing the operational plan.

- Anticoagulant rodenticides have been advised, as part of the Feasibility Study, to be the most suitable rodenticide to be used for eradication on Inchcolm. The use of anticoagulant rodenticides is currently the most widely recognised effective method of eradicating rodents from islands (DIISE, 2018).

- The eradication programme on Inchcolm would be a ground-based operation using bait stations. Anticoagulant rodenticide would be positioned in a bait station spread in a 25 metre x 25 metre grid across the island (170 bait stations) with special consideration for coastal cliff areas and archaeological areas.

- Each bait station would have an individual number, plotted using GPS and all data put into a GIS-linked database. Once all the bait stations were in position on Inchcolm, they would be left for one week or more (without toxin in them) so the rats became accustomed to them and accepted them as part of the terrain. Following this the anticoagulant rodenticide would be added to the bait stations.

- Bait stations would be checked a minimum of every two days, replacing bait as rats consume it. Partially eaten bait would be replaced with a new block. Old or partially eaten bait would be disposed of at a registered landfill or incineration facility as recommended by the safety data sheets. Checking bait stations would enable constant monitoring of bait take and the resulting die-off of rats. The success of the eradication and any problems, which need to be overcome during the programme, require the detail of accurate recording.

- Bait take would be recorded into GIS-linked database apps in the field for ongoing analysis. Refinements to the eradication phase could be made from this real time data. Hot spots could be identified quickly and targeted throughout the programme allowing for real time adaptive management.

- The eradication phase would be carried out in the winter when rodent numbers are naturally at their lowest, and when natural food supplies are low. This means that there would be fewer rodents to catch, and those that do remain are more likely to take the bait in the absence of other food sources.

- Baiting would begin in November and continue through to March (overlapping with the early intensive monitoring phase of the programme). Any surviving rats or problem areas would be apparent by the end of December and could be treated with an alternative poison or techniques.

Improvements to Seabird Nesting Habitat

- In addition to eradication, adaptions, improvements, or enhancements to nesting habitat for target seabird species would be implemented. This would be outlined in the Evaluation and Monitoring Plan produced as a result of the pre-eradication field studies. This would include options to accelerate occupancy of habitat by target seabird species, in particular the removal of tree mallow which has been identified as being present on Inchcolm and is known to infiltrate burrows and inhibit breeding for puffin.

- In addition, the accumulation of plastic litter on the beaches has been raised as a concern from initial stakeholder engagement. Although HES maintain the Abbey grounds there is currently no mechanism to remove plastic from the rest of the island. An annual plastic pick-up could be included within the annual monitoring to maintain Inchcolm in a better condition for seabirds and other wildlife such as seals.

Monitoring, Reporting and Adaptive Management

- A Monitoring and Evaluation Plan would be developed by the Applicant in consultation with HES, NatureScot, FSG and FIHG. Not only would this include details to monitor the success of the eradication programme but also would include seabird monitoring which would be required to establish whether the conservation targets are achieved.

Monitoring and Reporting

Approach to Monitoring

- Successful implementation of the eradication would contribute to improving both the number of seabirds nesting on Inchcolm and their breeding success.

- As stated above, a Monitoring and Evaluation Plan would be developed, pre-eradication, which would outline the various stages of monitoring as well as including progress indicators to allow the Applicant to determine the success of the compensatory measure. The monitoring would be reported against the progress towards the conservation targets for each species throughout the operational lifetime of the Proposed Development. The stages of monitoring would include immediate monitoring, long term monitoring and seabird monitoring. These are outlined in turn below.

Immediate Monitoring

- Once the baits have been set, early monitoring and surveillance would be required to assess the success of the baits. This would involve maintaining bait stations, searching, recovering and disposing of rat carcasses, installing and maintaining a monitoring network and implementing local biosecurity measures (as discussed above). The Applicant would ensure there is sufficient resource and funding to identify any incursion and seek to intercept any rat before it could breed and re-establish a population, for example a biosecurity warden to lead on this with support from HES staff as appropriate.

- The coverage of the monitoring grid would extend beyond that of the bait stations; one monitoring point at the station and one in-between two stations. Each monitoring site would be checked every two days to detect rat sign (for example teeth marks or footprints or footage on camera). If any rat sign is detected, an intensive targeting programme would be started until rat sign in the area ceases.

- All intensive monitoring points would be recorded on GPS, entered into the GIS-linked database, and mapped to ensure coverage of the island.

- After about six weeks, bait take should be reduced to nil, with all the rats on Inchcolm having been eradicated. During the following three months it would be vital to establish an intensive monitoring programme to detect any rats which may have escaped eradication. A grid of rat-attractive food items as well as chew cards would be pegged out as monitoring tools. Tracking tunnels and trail cameras would also be used. Beach surveys for footprints in the sand would also occur.

- It is expected that the monitoring phase of the programme would begin from mid-December following the eradication campaign. The bait station grid could be removed once the intensive monitoring phase has been completed and rat sign is absent. If rats are detected at the end of winter (i.e., February and/or March) a second baiting (i.e. during the following winter) and continued monitoring operation would be completed to finish the eradication.

Long-Term Monitoring

- Following international best practice, long-term monitoring for surviving (or reinvading) rats would continue for two years between the end of the eradication phase before declaring the island rat-free. This is based on the average life expectancy of a wild adult rat (which is approximately 18 months).

- The two-year long-term monitoring programme would be continued for at least every four weeks throughout the year to confirm the success of the eradication phase (i.e., to detect any surviving (or possible invasion) of rats). Permanent monitoring stations would be placed around the island (i.e., within known seabird areas, optimum rat habitat and in high-risk areas) to aid with detecting any surviving rats or intercepting invading rats.

- Once the two-year monitoring phase has been completed and no rats have been detected, one further intensive island-wide monitoring check would be completed. This would involve putting a range of monitoring devices over the entire island and checking every two days for six weeks. Once this check is completed and no rats have been detected the island can be declared rat-free.

- All long-term monitoring points would be recorded on GPS, entered into the GIS-linked database, and mapped to ensure coverage of the islands. Any sign or indication of rodents would be photographed and if possible, collected or sampled for expert opinions on identification.

- This long-term monitoring for the presence of rodents after an eradication operation would be done as part of the biosecurity programme and would be undertaken by the Applicant’s Biosecurity Warden with support from HES staff on the island. It would be important to monitor using a range of detection devices (such as flavoured and plain wax, chew cards, traps, rodent motels, trail cameras and indicator dogs) and have a regular search effort. Low numbers of rats may take longer to detect than realised. It may also be possible to use the recovery of vulnerable species (such as puffin) or establishment of prospecting species (such as Manx shearwater and storm petrel) to indicate that rats have been successfully eradicated.

- It would be important to use a variety of lures and monitoring techniques regularly throughout the biosecurity and long-term monitoring for rodent incursions. Periodic audits and on-going monitoring of these biosecurity measures would be completed to ensure compliance and support. It is important that all involved realise that biosecurity is a long-term ongoing commitment.

- Protocols would be established, and outlined with the Communication and Engagement Strategy, during the eradication and training given to local HES staff and the landowner to ensure that biosecurity measures would be implemented alongside the long term monitoring, as funded by the Applicant.

Seabird Monitoring

- Once the island is declared rat free, seabird monitoring would be undertaken, the Monitoring Plan would be developed in consultation with stakeholders.

- Monitoring may involve taking colony counts and recording data on productivity (i.e. number of chicks fledged per breeding pair). Colony counts would need to be undertaken using the published methodologies, which differ for each of the target species. To effectively monitor productivity, two to five visits may be required for Kittiwake, two to six visits for Razorbill, and two to four visits for Puffin. Monitoring Guillemot productivity is extremely difficult and would require three visits during late incubation/early hatching and visits every one to two days once most chicks are hatched (Gilbert et al. 1999).

- Seabird counts would follow the methodology used for the Habitat Assessment undertaken in 2022, in consultation with local groups, inclusive of detailed photographic record of recovery across unoccupied habitat.

Approach to Reporting

- The monitoring outlined above should be considered as progress indictors to be used to measure the success of eradication (i.e. the island being declared rat free) against the outcomes of seabird monitoring and the progress towards the conservation targets for each species throughout the operational lifetime of the Proposed Development. This would be detailed in annual monitoring reports.

- At the end of each year once the eradication programme has commenced an annual report would be produced. The annual monitoring report could follow this structure:

- Overview of evidence of rat re-incursion (if any)

- Overview of implementation of biosecurity measures

- Overview of the results from seabird monitoring (section only included once island is declared rat free)

– Colony counts

– Mapping nest locations

– Productivity monitoring

- Actions delivered

– Actions to manage biosecurity

– Actions to improve seabird habitat

- Identification of emerging issues

- Approach to biosecurity measures for the following year

- Approach to monitoring for the following year

- The annual monitoring reports and data collected would be shared with key stakeholders including HES, NatureScot, RSPB, FSG and FIHG and all data collected made publicly available where appropriate. The results of the monitoring report would be used to update the Biosecurity Plan and subsequent implementation of measures to improve seabird habitat.

- If any re-incursions did occur and the Incursion Response Plan was implemented a report summarising the likely cause of the incursion, the approach taken for further eradication and adaptive management measures to be implemented would be prepared.

Programme for Implementation and Delivery

- As discussed previously, this compensatory measure is considered a secondary measure which would only be implemented in the event that monitoring shows the other compensatory measures are not progressing towards their conservation targets. As such, an implementation programme has not been progressed. Nevertheless, due to the similarities of this secondary compensatory measure and the compensatory measure proposed to be implemented at Handa, the timescales outlined in the indicative programme presented in section 3.5 are also applicable to Inchcolm.

Adaptive Management

- The approach to adaptive management for this secondary compensatory measure is considered in two parts. Firstly, adaption in response to re-incursion or biosecurity failure, and secondly, adaption in the form of habitat management.

- Maintaining the island rat free is key to achieving the objectives of the secondary compensatory measures at Inchcolm. Should the reoccurrence of rodents be detected the Incursion Response Plan would be implemented and followed. If re-incursion is a result of a failure of eradication, adaptive solutions could include different locations of bait stations, different bait, alternative rodenticide to be used or trapping for example. If re-incursion was a result of a failure in biosecurity measures the Applicant would seek to work with HES, the qualified contractor, vessel operators and other visitors/users of the islands to understand why the biosecurity measure failed and implement alternative measures to ensure biosecurity was maintained. The Communication and Engagement Strategy would also be re-visited and adapted as appropriate.

- In the event that monitoring shows that this secondary compensatory measure is not progressing towards its conservation targets (as defined above) new measures would be developed, or adaptions made to managing seabird habitat. Key to the success of this approach is for the annual monitoring reports to identify emerging issues, and where necessary gather data and develop adaptive management solutions and corrective measures. These adaptive management measures could include:

- Artificial ground cover could be considered as an adaptive measure following rat eradication, to further increase breeding performance at potential cliff-top breeding sites as well as artificial nesting boxes.

- Social attraction methods, such as playbacks and decoys, could be used to increase the likelihood of recruitment.

- Vegetation management, comprising reduction in height and density of grasses and shrubs and loosening of soils on tops of steep slopes could be adopted prior to the start of the nesting season to optimise conditions and create space and access for target seabird species, notably burrow nesting puffin.

- White paint could be used to simulate guano at potential breeding sites This could be used for the auks, potentially alongside the use of vegetation management, decoys and playbacks, with the aim of increasing colonisation rates following rat eradication.

6. Approach to Consent Conditions

- The Applicant has presented a range of compensatory measures to offset the potential impact of the Proposed Development. These measures are substantial, and reasons and evidence have been provided that should give Scottish Ministers confidence that they can be secured and will be effective.

- The compensatory measures are split into two categories, firstly colony-based measures, that include proposals to eradicate rats from Handa Island as well as the funding of a new warden post at Dunbar Castle to reduce human disturbance and implement other measures to support the kittiwake colony. These measures work by increasing seabird productivity. However, rat eradication doesn't just affect productivity but also the available space for birds to breed, so increases in population size can be very rapid as previously unsuitable space for nesting becomes suitable. This should attract recruits to these spaces, adding to the population, through immigration. Secondly, the applicant has proposed measures to improve the management of Sandeel fisheries via a full closure of SA4 or the implementation of an ecosystem- based fisheries management plan. These fisheries-based measures work by increasing productivity but also by improving the survival of adults and immature birds.

- These measures provide a comprehensive solution that will maintain and enhance the national site network. However, an understanding of the timing of the effects of the compensatory measures is also required to allow Scottish Ministers to be confident that the measures will maintain the coherence of the network. This issue has been considered in recent decisions for offshore wind farms in English Waters.

6.1. Development Consent Order conditions relating to timing of measures

- The UK Government’s Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy has consented five offshore wind farm projects with associated derogation cases in the last two years. Hornsea Three in 2020 and East Anglia ONE North, East Anglia TWO, Norfolk Vanguard and Norfolk Boreas in 2022. All five projects have included a similar condition on the timing of compensatory measures for kittiwake and lesser black-backed gull that relate to two compensatory measures – installation of kittiwake breeding towers and the installation of predator exclusion fencing for lesser black-backed gulls.

- The condition states that “…no operation of any turbine forming part of the authorised development may begin until four full breeding seasons following the implementation of the measures set out in the [Implementation and Monitoring Plan] have elapsed…”. It is understood that this time lag has been put in place to allow the compensatory measures to become effective and offset the impacts of the development before the harm occurs. This time lag is based on the specific nature and scale of the compensatory measures proposed.

- The first of these measures, the implementation of kittiwake breeding towers leading to the development of a new colony, seeks to offset the impacts of development by recruiting new adult birds into the SPA population. However ultimately the success of the measures relies on the ability to increase productivity at this new colony and increase the number of adult birds. The second measure, the installation of predator colony fencing aims to reduce the predation of eggs from ground nesting birds. This reduction in predation, it is assumed, will lead to an increase in the number of fledged chicks and an increase in the number of adult birds.

- Both measures rely on an increase in productivity leading to an increase in adult birds to offset impacts. Seabirds take time to reach breeding age and therefore a period of a few years may be required to allow this process to become effective, justifying the consent conditions above.

- Another key assumption underpinning this argument is that compensatory measures should be operational at the time that the harm occurs. However, this may not always be necessary as the relevant guidance does make provision for compensation to be effective after harm has occurred, but only in certain circumstances. If these circumstances do occur, then overcompensation would be required for these interim losses.

- In the case of the kittiwake breeding towers and predator exclusion fencing the benefits are likely to be relatively small and it would be difficult to justify a delay in the effectiveness of compensatory measures as the potential for overcompensation and the delivery of wider ecological benefits is limited.

- However, as explored below, the compensatory measures outlined for the Proposed Development are of a different order of magnitude and the ecological mechanisms by which impacts will be offset are different. This means that firstly, the results of the proposed compensation measures for the Proposed Development are likely to be operational at the time the impacts occur, if not before. Secondly that the compensation measures have such high compensation ratios that benefits are likely to occur very shortly after the measures become fully effective. Further detail on these two points is set out below.

6.2. Compensation for the Proposed Development

Introduction

- The Applicant has proposed two categories of compensation. Measures which focus on improving productivity at relevant colonies and fisheries-based measures that aim to improve prey availability leading to both an increase in productivity and overwinter survival. These measures are complementary and, when implemented, are likely to provide significant long-term benefits to the seabird population.

- The objective of implementing these compensatory measures, as set out in the Habitat Regulations, is to ensure the coherence of the National Site Network, given the potential negative impacts of the development. It is important to consider this overall objective when considering the points presented below.

Timing of Impact

- To ensure that compensatory measures will be effective before harm occurs it is important to have a realistic view of when the impacts will occur. The Proposed Development is a very large project and construction is planned to take place over several years, starting in 2025. Whilst the assessments of site integrity undertaken for the RIAA have assumed that the impacts will commence at the start of construction, in reality they will be lower at the start of the project and increase to the point at which the site is fully operational. Therefore, in considering the timing of the impacts and the effectiveness of the compensatory measures it is important to note that all the impacts will not occur immediately. For a multi-year construction period it would be reasonable to assume that the impacts are proportional to the rate of build out. i.e. they do not all occur in year one. This more granular understanding relates only to the timing of the impacts in relation to the timing of the benefits, not the total amount of compensation required to offset the impacts assessed in the RIAA.

- Furthermore, an assessment of site integrity at the end of a multi-year construction period is likely to conclude that there is no effect on the coherence of the national site network compared to the impact after 35 or 50 years of continued negative impacts on the relevant SPAs. This means that it is likely that, even if negative impacts have started to occur, then they are unlikely to be any effect on the coherence of the national site network. These two reasons suggest that it would be reasonable, for a project of the scale of the Proposed Development, to implement compensatory measures at, or shortly before, operation.

Sandeel measures impacting adult and immature survival

- There is no need to provide for a delay between implementation of sandeel measures and operation of the first turbine because of the way in which the Sandeel measures will offset the impacts of the development. Whilst colony-based measures work by increasing productivity, measures to increase the availability of sandeel also lead to an increase in survival. An immediate increase in the sandeel TSB as a result of removal or reduction in fishing pressure (as set out below) is likely to lead to an immediate increase in adult survival providing like for like compensation, with no requirement to allow chicks to fledge and enter the adult population. Our assessment of benefits from the proposed sandeel measures took a conservative approach and only quantified the benefit to adult birds. However, the same effect will also apply to immature birds delivering an increase in the population ready to enter the adult breeding population.

Small changes in adult survival needed to offset impacts

- Only very small changes in survival rates are needed to offset the potential negative effects of the development. The fisheries compensatory measures evidence report sets out a range of scenarios for the change in the Sandeel TSB, and the increase in survival rates that could be expected from those changes. For example, this relationship for kittiwake demonstrates that the most conservative scenario, an increase in TSB from 300,000 to 400,000 tonnes, would result in an increase in survival rates from 0.8520 to 0.878. This change would generate an additional 3,871 kittiwakes per annum from changes to survival of adult birds alone across seven SPAs in proximity to SA4. This is considerably higher than the increase needed offset the potential impacts of the development of 669 kittiwakes per annum under the most precautionary assessment in the RIAA.

Sandeel TSB response to removal or reduction in fishing pressure

- The average sandeel TSB over the last ten years has been 264,293 tonnes and the SSB has averaged 103,812 tonnes. This indicates that there is likely to be sufficient productive stock in the population that can generate the increases that are required if fishing pressure is removed. It is recognised that full recovery of the stock may take several years, but this full recovery is not needed to generate the benefits that are required in the short term.

- In addition, the setting of a zero TAC for SA4 at the outset (or closure of SA4) means that sandeel, that would ordinarily have been removed from the stock by fishing vessels, will be immediately available for seabirds and lead to an increase in survival and productivity.

- In conclusion on compensation, therefore, during the construction phase of the wind farm any impacts that occur will be lower than those used to assess the impacts on SPAs. The impacts during this period are unlikely to result in an effect on the coherence of the national site network and in any case will be offset by the implementation of Sandeel compensatory measures that will provide a like for like compensation via the mechanism of increased survival.

- Whilst this discussion presents a robust argument that the proposed compensatory measures will ensure that the coherence of the National Site Network is maintained through the implementation of the proposed measures, the relevant guidance does allow for interim losses if overcompensation is provided. The next section provides further detail on this guidance and an interpretation in the context of the Proposed Development.

6.3. Timing of compensation and overcompensation

EU Guidance

- The 2018 EC guidance on managing Natura 2000 sites indicates that the timing of compensation should be considered on a case-by-case basis. Of overriding importance is the need to maintain continuity in the ecological processes that are essential to support the coherence of the National Site Network. Further key issues that need to be considered include:

- Site must not be irreversibly affected before compensation is in place

- The result of compensation should generally be operational at the time the damage occurs at the site concerned. However, under certain circumstances where this cannot be fully achieved, overcompensation would be required for the interim losses,

- Time lags might only be admissible when it is ascertained that they would not compromise the objective of 'no net losses' to the overall coherence of the Natura 2000 network.

- In the context of the Proposed Development, the removal and reduction of Sandeel fishing pressure in SA4 would maintain the continuity of the ecological processes, i.e. provision of prey, that is required to support the coherence of the network. To address the further considerations, sites would not be irreversibly damaged before compensation is in place, because the impacts will start at a lower level and only be at the higher level assessed in the RIAA when the site is fully operational. In any event, damage would not be irreversible in the same way that, say, loss of ancient woodland would be, since measures can be taken to increase the population. Even if the higher impacts occur without operational compensation, they are unlikely to result in an adverse effect on coherence of the national site network.

- The second consideration suggests that under certain circumstances where the results of compensation are not fully operational before the impacts occur then overcompensation for interim losses would be required. The circumstances under which this might be possible are not explored in any more detail in the guidance. However, it would be reasonable to assume that this refers to ecological circumstances where the restoration of habitats, such as ancient woodland, cannot be fully achieved. It would also be reasonable to include circumstances where the impacts occur before compensation is operational as a result of the delivery of substantial renewable energy projects to combat climate change, the greatest medium-term risk to the coherence of the national site network. It would be rational to expedite the delivery of renewable energy projects to reduce the impacts of climate change particularly where it can be demonstrated the proposed compensatory measures associated with the development will ultimately lead to an increase in the resilience of the network rather than just offsetting the potential impacts. The Sandeel measures proposed will deliver this increase in resilience because of the high compensation ratios which this measure will deliver.

- This rationale also supports the argument that time lags may be admissible where they would not compromise the objective of no net losses to the overall coherence of the network. The FCM Evidence Report provides robust evidence to demonstrate that better management of the Sandeel Fisheries in SA4 will lead to a substantial increase in the seabird population at SPAs across the national site network. Furthermore, whilst the colony measures work by increasing seabird productivity, rat eradication at Handa will provide further available space for birds to breed, so increases in population size can be very rapid as previously unsuitable space for nesting becomes suitable. This should attract recruits to these spaces, adding to the seabird population, through immigration.

DEFRA Guidance

- Defra guidance states that “Compensatory measures should usually be in place and effective before the negative effect on a site is allowed to occur”. It is therefore clear that in certain circumstances a time lag between compensation becoming effective and the impact is acceptable. The EC guidance provides greater clarity and sets out the key issues that need to be considered when assessing the potential for a time lag to be acceptable. It would be entirely reasonable for Scottish Ministers to take the same view. The unique nature of the compensation proposed for the Proposed Development means that these issues can be resolved positively and a time lag, if needed, would be acceptable.

6.4. Conclusion

- This section has examined the consent conditions that have been applied to the five offshore wind farms under the Development Consent Order process. These conditions require that operation of the first turbine cannot take place until four breeding seasons have elapsed from the implementation of the compensatory measures. This is due to the demographic limitations inherent in the compensatory measures, i.e. via an increase in productivity and the limited opportunity to provide overcompensation. The compensation measures proposed to be implemented for the Proposed Development are fundamentally different in their operation and scale.

- Reasons and evidence have been presented to demonstrate that the proposed compensatory measures at the Proposed Development are likely to offset impacts that may compromise the coherence of the National Site Network without a significant time lag. Notwithstanding this, it is important to note that both relevant sets of guidance allow for a time lag to occur under certain circumstances. This is most likely to allow for long-term ecological processes associated with some measures to become established, but justification for a time lag would also reasonably include the urgent need to deliver renewable energy at scale to address the climate and biodiversity crisis and increase the resilience of the national site network.

- Based on the arguments presented above the applicant has prepared draft conditions that will provide the required level of confidence to Scottish Ministers that the compensatory measures will be secured, and the coherence of the national site network will be maintained.

6.5. Proposed Consent Conditions

- This section provides the Applicant’s proposed draft consent conditions which the Scottish Ministers could include as part of the Section 36 consent for the Proposed Development.

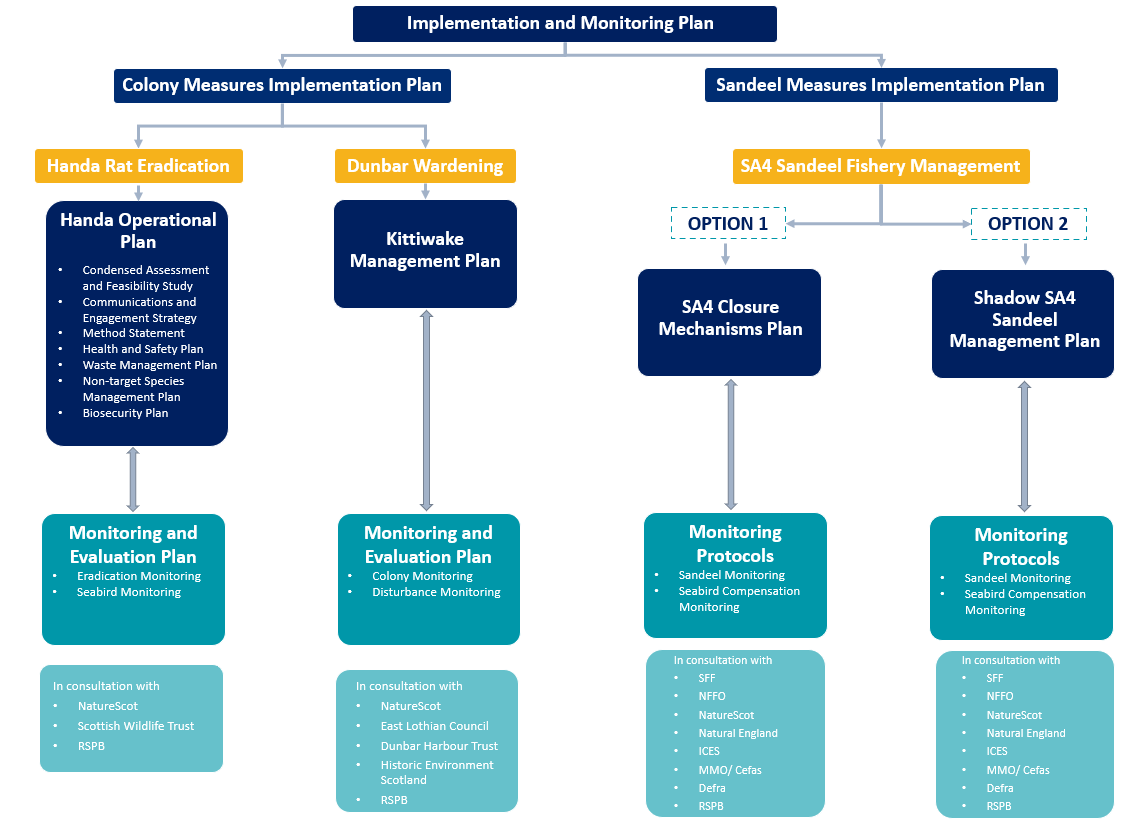

- Figure 4 provides an overview of the documentation which would be produced by the Applicant in consultation with various stakeholders and submitted to Scottish Ministers for approval as part of the consents discharge process.

Proposed Consent Conditiions

“Implementation and Monitoring Plan” means the plan with that title dated 9 December 2022 submitted with the Application.

- The Company must, no later than 6 months prior to the Commencement of Development, submit a Colony Measures Implementation Plan (CMIP), in writing, to the Scottish Ministers for their written approval. Such approval may only be granted following consultation by the Scottish Ministers with any advisors or organisations as may be required at the discretion of the Scottish Ministers.

The CMIP must be based on the Implementation and Monitoring Plan and set out:

- An implementation timetable for the delivery of the compensatory measures; and

- Details of any proposed monitoring and reporting, and adaptive management.

The CMIP must be implemented as approved (including any updates or amendments). No wind turbines forming part of the Development may become operational unless and until all those measures required by the approved CMIP to be implemented prior to the operation of the wind turbines have been implemented and the Scottish Ministers have confirmed this in writing.

Any updates or amendments to the CMIP by the Company must be submitted, in writing, by the Company to the Scottish Ministers for their written approval.

- The Company must, no later than 6 months prior to the Commencement of Development, submit a Sandeel Measures Implementation Plan (SMIP), in writing, to the Scottish Ministers for their written approval. Such approval may only be granted following consultation by the Scottish Ministers with any advisors or organisations as may be required at the discretion of the Scottish Ministers.

The SMIP must be based on the Implementation and Monitoring Plan and set out:

- An implementation timetable for the delivery of the compensatory measures; and

- Details of any proposed monitoring and reporting, and adaptive management.

The SMIP must be implemented as approved (including any updates or amendments) in so far as applying to the Company. No wind turbines forming part of the Development may become operational unless and until all those measures applying to the Company required by the approved SMIP to be implemented prior to the operation of the turbines have been implemented and the Scottish Ministers have confirmed this in writing.

Any updates or amendments to the SMIP by the Company must be submitted, in writing, by the Company to the Scottish Ministers for their written approval.

Figure 4 Plans to submitted to Scottish Ministers for Approval, as well as proposed consultees