3. Historical decarbonisation and policies for the future

3.1. Nationally Determined Contributions

- NDCs are stepping stones to achieving Net Zero commitments and policies are therefore in place to support Scotland (and the UK) to the progressive achievement of Net Zero. This section describes how Scotland and the UK have performed against their legislative targets to date; and sets out the current plans and policies in place to deliver further decarbonisation. It lists those Scottish (and UK) policy positions which are driving emissions to Net Zero and which are relevant to the Project.

- The Scottish government has its own statutory emissions reduction targets. The Scottish NDC publication quoted above also refers to the Scottish NDC (which align with the commitments made in the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 as amended) and were informed by the Paris Agreement. Progress towards these targets also contributes to achievement of UK-wide targets. The decision on the UK’s NDC headline target was led by BEIS and agreed through UK Government governance structures at official and ministerial levels. The target level in the UK's NDC was informed by the UK’s commitments under the Paris Agreement, the legally-binding net zero commitment, and guidance from the CCC.

3.2. How decarbonisation has been achieved to date

- UK territorial greenhouse gas emissions, including those from power generation, have reduced since 1990, as shown in Figure 3‑1. Over the period 1990 to 2021, power station emissions reduced to just 26% of their 1990 value while emissions from other sectors reduced to 61% of their 1990 value [11]. This was despite Total Final User Electricity Consumption (a BEIS definition) in the UK increasing from 274.4TWh to 286.1TWh over the same period [12]. Reductions in the UK power sector have been achieved through many initiatives and circumstances.

- Electricity volumes generated from coal and gas fired power plants has reduced. The Large Combustible Plant Directive (aiming to improve air quality but also having significant carbon reduction benefits) required the clean up or time-limited operation of coal-fired power generation prior to 2016. Between 2012 and 2015, at least 11.5GW of coal plant decommissioned as a result of the Directive and Scotland's last coal fired power plant closed in 2016.

- GB’s second-generation nuclear fleet (9GW) has operated significantly past its original decommissioning dates. Nuclear provided 16% of electricity demand in 2020 from two stations in Scotland (2.3GW) and six stations in England (6.8GW), all with low carbon emissions [13], however the decommissioning of existing plants commenced in 2021 including 1.0GW in Scotland and 2.1GW in England. Advances in new nuclear plants to replace the existing fleet have been slower than was originally foreseen (see Section 5.3.2).

Figure 3‑1: UK territorial greenhouse gas emissions 1990 to 2021

[11]

- The transformation of Scottish electricity generation capacity over the last six years has been charted in Figure 3‑2. Scotland's last coal fired power plant closed in 2016. Hunterston and Torness nuclear power stations have run on past their original end of life estimates. Hunterston has just recently closed after more than 45 years of low carbon electricity generation, and Torness is currently capable of operating at full power 1.3GW). As of March 2022, Scotland had 13.3GW of renewable electricity generation capacity, of which 8.7GW was onshore wind and 1.9GW was offshore wind [14]. The CCC recognise that there are now only limited further reductions possible from electricity generation, so meeting Scotland's climate change targets now requires significant progress on decarbonisation across a range of other sectors including the electrification of transport, heat and industrial demand, which in turn requires an increase in low carbon electricity generation capacity [15].

- Decarbonisation of electricity generation in the UK has been achieved in very similar ways, see Figure 3‑3. In late 2017, UK government announced a commitment to a programme that will phase coal out of all electricity generation by 2025, a date which during 2020 was brought forwards to 2024. National carbon pricing aims to attribute additional marginal costs (see Section 8.2) to coal plant, therefore signalling their dispatch only when other less carbon intensive assets have been exhausted. In June 2020, Britain ended a record run of not generating any electricity from coal for 1,630 consecutive hours – the longest period since the 1880s. In 2019, many asset operators announced the closure of their coal generation assets. Just one coal station (Ratcliffe, 2.0GW) remained commercially operational beyond September 2021 with four other units (two at West Burton A and two at Drax, with a combined generation capacity of 2.2GW) responding to system stress events only since 1st October 2021 until their closure (currently scheduled for March 2023). Ratcliffe is currently signalling that it will close by [Author Analysis].

Figure 3‑2: Estimated Scottish commercially operational capacity, Q115 - Q422

[Author Analysis]

- Low carbon variable generation, predominantly wind and solar, has been deployed to the GB grid more quickly and more widely than originally projected. At the time of writing this report, 13GW of offshore wind and 13.6GW of onshore wind has already been “built” and connected to the NETS as at July 2022 (i.e. is in an operational status), with a further (estimated) 13.8GW of solar PV connected to distribution networks [107].

- Investors have increasingly been attracted to technologies (such as renewables) which are eligible for government-backed support programs (such as the Contract for Difference), which address the market risk and long-term price uncertainty associated with the GB electricity market. Interest from investors and developers in these technologies has driven technical development and competition on cost. Consequently, UK government has repeatedly confirmed the important role the CfD mechanism plays in bringing forwards new large-scale low carbon generation, and Allocation Round 4 (AR4) contracts were awarded in the summer of 2022. As an indicator of the importance of wind as a technology class within the evolving GB electricity system, and an indicator of the competitive cost of the technology, over 8.5GW of wind capacity across 22 projects secured Contracts for Difference (CfD) in AR4, at an initial strike price ranging from £37.35/MWh (Offshore Wind) to £87.30/MWh (Floating Offshore Wind). All CfDs commence in either 2024/25 (Onshore Wind) or 2026/27 (all Offshore Wind technologies).

Figure 3‑3: Estimated UK commercially operational capacity, Q115 - Q422

[Author Analysis]

3.3. The urgent need to decarbonise

- The timescales for building out new, large-scale generation projects are generally long. Those in planning today may not generate their first MWh of carbon-free electricity for a further 5 or more years. However the need for decarbonisation grows stronger each year, because every year during which no action is taken, more carbon is released into the atmosphere, global temperatures rise and the global warming effect accelerates. Therefore early action will have a correspondingly more beneficial impact on our ability to meet Net Zero targets than will later action. The Project is already well progressed in development, so can deliver much needed large scale capacity much sooner than other projects moving into development. In June the International Energy Agency (IEA) issued a call to arms on energy innovation, stating that the world “won’t hit climate goals unless energy innovation is rapidly accelerated ... About three-quarters of the cumulative reductions in carbon emissions to get on [a path which will meet climate goals] will need to come from technologies that have ‘not yet reached full maturity” [17]. DNV GL expressed this observation in a different way: "Measures today will have a disproportionately higher impact than those in five to ten years’ time” [18].

Figure 3‑4: Power generation emissions must reduce to negative in the early 2030s in order to meet 2050 Net Zero targets

[107]

- Section 4.3 will explain that the pathway for both Scotland and the UK to achieve Net Zero must involve wider transitions outside of the power generation sector. Therefore, the power generation sector must first decarbonise in order to enable the successive decarbonisation of transport, industry, agriculture and the home. While the CCC have suggested that this is already the case in Scotland [15] they have also noted the significant progress required in decarbonising other Scottish sectors, and therefore new low carbon generation capacity is required in Scotland in order to meet additional demand for electricity. Not only will new low carbon generation in Scotland reduce electricity imports to Scotland from the rest of the UK (which has higher average carbon emissions than indigenously generated Scottish low carbon generation) but also will act to reduce the UK's average power sector carbon emissions further. NGESO analysis points to the requirement to reduce emissions from the UK power generation sector to below zero in the early 2030s, as shown in Figure 3‑4. The scale and pace of change required within this sector, in order to meet a negative emissions target, is immense.

- Put simply, the urgency with which the power sector is required to be decarbonised is immense and actions must proceed with unrelenting pace. Any delay in reducing carbon emissions today results in more carbon to be emitted to the atmosphere, and global temperatures will rise. The speed with which subsequent carbon emissions must be halted therefore increases, or else the Paris Agreement aim of 1.5°C temperature rise versus pre-industrial levels comes under threat. A rise in global temperatures above 1.5°C comes with the potential for irreversible climate change, the potential for widespread loss of life and severe damage to livelihoods, and an urgent increase in the deployment of adaptive technologies to protect human existence from climate change. Any delays incurred now, make the challenge increasingly more difficult for the years ahead.

- The UK Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy [19] clearly states the objective for the 2020s, which “will be crucial ... to lay the bedrock for industrial decarbonisation. Over the next decade ... the journey of switching away from fossil fuel combustion to low carbon alternatives such as hydrogen and electrification [will begin, alongside] deploying key technologies such as carbon capture, usage and storage”. In conclusion, to address the ongoing climate emergency, it is critical that the UK develops a large capacity of low carbon generation, and it is critical that this development occurs urgently – in the near-term and not just later – to facilitate wider decarbonisation actions. It is also important for schemes with long development timescales to continue progressing their plans to achieve carbon reduction in decades to come.

- Developments with the proven ability to achieve savings in this decade, and even more importantly in the early part of this decade, must be consented. It is these developments which are most critical to keeping the world to its required carbon reduction path. An actual, potential or aspirational pipeline for longer term low carbon generation schemes presents additional opportunity for future decarbonisation, but does not present a valid argument against consenting and developing projects with proven near-term deliverability, and dependable decarbonisation benefits.

- The Project is a viable proposal, with a strong likelihood of near-term deliverability, which will achieve significant carbon reduction benefits through the deployment of a proven, low-cost technology in a very suitable location. As such, the Project possesses exactly those attributes identified as being required both in the near-term and in the future in order to continue to make material gains in carbon reduction.

3.4. Current Scottish policies to meet net zero

- Scotland has declared a climate emergency. As host of the Conference of the Parties 26 (COP26), held in Glasgow in November 2021, Scotland demonstrated its position of international leadership on climate change. In August 2021, the Scottish First Minister sent a letter to the Prime Minister [20]. The letter confirmed Scotland’s position at the “forefront of global efforts to achieve the aims of the UN Paris Agreement”; recognised that climate change, as an inherently global issue, “can only be addressed through co-ordinated international effort and working with others” and urged “all of us who hold positions of leadership to consider what more we can, and must, do to meet [the challenge to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C in the longer term]”. Scotland has established legally binding targets to meet Net Zero by 2045 at the latest with a world-leading interim 2030 target (which is also Scotland's legally binding indicative Nationally Determined Contribution) of a 75% reduction in emissions against a 1990/95 baseline [7]. Scotland's updated Climate Change Plan [21] sets out how Scotland will deliver that ambition. Scotland's targets and delivery plans are reflected in the UK's NDC commitments and as such Scotland is a critical contributor to the achievement of the wider UK’s NDC commitments.

- Scotland has progressively established policy positions related to climate change and the delivery of a just transition to incorporate and embed low carbon living into its social and environmental fabric. The Scottish government also recognises the benefits associated with capturing opportunities for growth in offshore wind and related services, including for domestic and international deployment. Since launching the Offshore Wind Sector Deal in March 2019, the Scottish and UK governments have worked together with the offshore wind sector to make progress on delivering the commitments that it contains. The Scottish government is represented across all main Sector Deal work streams, and is working closely with the UK government to deliver a number of key outputs from the Sector Deal because delivering against the Sector Deal commitments will help unlock Scotland's potential [22].

- Scottish Energy Strategy (2017) [23] established 2030 whole-system targets for Scotland. These were:

- The equivalent of 50% of the energy for Scotland’s heat, transport and electricity consumption to be supplied from renewable sources; and

- An increase by 30% in the productivity of energy use across the Scottish economy.

- Scotland's overall approach to energy within the context of Net Zero is driven by the need to decarbonise the whole energy system, in line with emissions levels set out in the Climate Change (Scotland) Act. The strategy recognises that “No-one can be certain what that future system will look like. However, we should be confident and ambitious about what we can achieve and deliver over the short to medium term, and focus on the areas where we know there are likely to be low or no regrets options.” A framework for the categorisation of options as being “low or no regrets” is included at Section 3.6.

- Future uncertainty in energy system evolution is modelled through two future scenarios: an “electric future” and a “hydrogen future”. In the electric future scenario, electricity generation accounts for around half of all final energy delivered. Electricity demand is consequently 60% higher than it was in 2015 and Scotland remains an integral part of the GB electricity system. In the hydrogen future, hydrogen is produced from strategically placed electrolysers and Steam Methane Reformation plants with Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS). While the strategy acknowledges that Scotland’s energy system in 2050 is unlikely to match either of these scenarios, it recognises that it will probably include aspects of both. Against this context, the development of a large, deliverable, cost-efficient offshore wind asset is a low regrets enabler of both.

- The strategy describes how the Scottish Government will continue to champion and explore the potential of Scotland’s huge renewable energy resource, and its ability to meet local and national heat, transport and electricity needs – helping to achieve Scotland's ambitious emissions reduction targets. The strategy also places a firm emphasis on the energy sector’s economic role, benefits and potential, from established technologies to those that are new or still emerging. Scotland continues to lead global efforts to decarbonise and tackle climate change, and to be recognised internationally for doing so.

- In 2021, Scottish Government released a position statement which provides an update on those policies set out in the Scottish Energy Strategy (2017). It reinforces Scottish commitment to remain guided by the key principles set out in Scotland’s Energy Strategy in 2017 and the importance the Scottish Government attaches to supporting the energy sector in its journey towards Net Zero. Scotland's Energy Strategy Position Statement [24] describes the continued growth of Scotland’s renewable energy industry as fundamental to enabling the creation of sustainable jobs as well as enabling the transition to net zero. The Scottish Offshore Wind Policy Statement [22] and Sectoral Marine Plan for Offshore Wind Energy in Scotland [25] describe the importance of offshore wind to Scotland’s economy.

- The Scottish Offshore Wind Energy Policy Statement sets out Scotland's ambition to capitalise on the potential that offshore wind development can bring, and the role that the technology could play in meeting Scotland's commitment to reach net zero by 2045. It explains that Scottish offshore wind generation will play a vital part in helping Scotland meet its hugely challenging climate change targets, effectively and affordably, while taking into account wider environmental factors and the interests of other users of the sea. Offshore wind is stated as being one of the lowest cost forms of electricity generation at scale, offering cheap, green electricity for consumers. It is also recognised in the Scottish Offshore Wind Energy Policy Statement, that offshore wind has the important potential for connection with green hydrogen production at scale, which adds another potential layer to Scotland’s rich energy portfolio. The Scottish Offshore Wind Policy Statement supports the development of between 8 and 11GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030, and the Sectoral Marine Plan supports the Scottish government's view that this capacity of offshore wind capacity is possible in Scottish waters by 2030. This Plan recognises that Scottish waters offer significant potential to maximise opportunities to deliver a green recovery, meet Scotland's ambitious targets for Net Zero and build a Blue Economy (defined by the World Bank as the “sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and jobs while preserving the health of ocean ecosystem”). The Plan provides the framework for the pivotal role that offshore wind energy will play in redeveloping Scotland’s energy system over the coming decades.

- However the Sectoral Marine Plan also recognises that as the amount of planned and constructed offshore wind development increases, opportunities to install offshore wind farms close to shore and/or in shallower waters will decrease, resulting in the need to explore opportunities to develop sites located further offshore and/or in deeper waters in order to capitalise on the potential that offshore wind offers to Scotland. The Sectoral Marine Plan provides the strategic framework for the first cycle of seabed leasing for commercial-scale offshore wind by Crown Estate Scotland (CES), the “ScotWind” leasing round, for which Plan Options have been identified across four deeper water regions (see Figure 3‑5). Results of the ScotWind leasing round were announced in January 2022 and an analysis of the results is at Section 3.7.

- Offshore wind developments which are sited either further offshore or within deeper water locations are described in the Sectoral Marine Plan as posing technical and financial constraints which are “new” - i.e. are not present in closer to shore and/or shallower water developments. Such constraints will need to be overcome in order to secure the success of deeper water projects.

- Scotland's Climate Change Plan 2018 - 2032 (published in 2018) was updated during 2020 [21]. It sets out in detail the role that electricity generation will have in the wider energy system and restates Scotland's commitment not only to deliver to its decarbonisation targets, but also to continue to ensure a future with a sustainable security of electricity supply. The update states that carbon capture and storage is essential to reach net zero emissions and includes the focussed contemplation of negative emission technologies and hydrogen to deliver clean cross-sector energy supplies. Specifically, the update envisions that in 2032, at least 50% of Scotland's energy demand across heat, transport and electricity will be met from renewable sources; and that there will be a substantial increase in renewable generation particularly through new offshore and onshore wind capacity. Passenger travel by rail and private road transport will also be largely decarbonised and home energy use will also be on a path to the adoption of electricity-based solutions for heat which take advantage of the large potential for growth of onshore and offshore wind capacity in Scotland.

- Recognising that the decarbonisation of heat, industry and transport are now priorities and require a broader range of technologies, strategies and energy systems, Scotland's Hydrogen Policy Statement [26] recognises the abundance in Scotland of the ingredients in green hydrogen production - water and wind - and seeks to enable Scotland to become producer of the lowest cost hydrogen in Europe by 2045. The scale of the hydrogen market depends on its cost, so driving down the cost of offshore and onshore wind electricity production will be key to cost-effective green hydrogen production. Recognising that large scale renewable hydrogen production may also provide essential energy balancing and flexibility functions to integrate the expected large increases in offshore wind into the UK energy system, Scottish Government will work with the UK Government to ensure alignment of policies and to ensure that market mechanisms are developed in tandem to reflect this system need.

- Scotland currently opposes the build of new nuclear stations using current technologies because of the poor value for consumers that the Scottish Government believes they provide. However, the Scottish Government recognises an increasing research and industry interest in the development of new nuclear technologies such as Small Modular Reactors. Scotland's policy position is therefore is that it has a duty to assess all other new nuclear technologies based on their safety, value for consumers, and contribution to Scotland’s low carbon economy and energy future.

3.5. Current UK policies to meet Net Zero

- The UK’s NDC draws on the following policy positions, some already in place and others in development or to be developed.

- The Clean Growth Strategy [2] contains UK Government’s current policies and measures to decarbonise all sectors of the UK economy through the 2020s and beyond. Of particular relevance to this Statement of Need, are: the roll out of low carbon heating to UK homes; accelerating the shift to low carbon transport; and delivering clean, smart and flexible power, including the development and delivery of an ambitious Sector Deal for offshore wind.

- In March 2019 the UK government announced its ambition to deliver at least 30GW of offshore wind by 2030, as part of the Offshore Wind Sector Deal [27]. The Sector Deal reinforced the aims of the UK’s Industrial Strategy and Clean Growth Strategy, which seeks to maximise the advantages for UK industry from the global shift to clean growth, and in particular: “The deal will drive the transformation of offshore wind generation, making it an integral part of a low-cost, low carbon, flexible grid system.” The deal paved the way for further ambition in the offshore wind sector. The Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan [28], which aims to “make the UK the Saudi Arabia of wind with enough offshore capacity to power every home by 2030,” confirmed the upward revision of the capacity of offshore wind targeted for deployment in UK waters by 2030 from 30GW to 40GW. The Ten Point Plan also advances the UK’s electric vehicle charging infrastructure and battery manufacture capability, and targets investment to “make homes, schools and hospitals greener, and energy bills lower”.

- The 2020 Energy White Paper [29] sets out government’s strategy to tackle climate change. It explains how the UK “will generate new clean power with offshore wind farms, nuclear plants and by investing in new hydrogen technologies ... [using] this energy to carry on living our lives, running our cars, buses, trucks and trains, ships and planes, and heating our homes while keeping bills low”. The Energy White Paper anticipates that onshore wind and solar will be key building blocks of the future generation mix, along with offshore wind, explaining that the UK needs sustained growth in the capacity of these sectors in the next decade to ensure that it follows a pathway which will meet net zero emissions in all demand scenarios by 2050. Key policy statements include eliminating the use of natural gas to heat our homes; ensuring that clean electricity becomes the predominant form of energy while retaining the essential reliability, resilience and affordability of UK energy supply; and decarbonising transport. Specifically, the Energy White Paper reiterates the revised Offshore Wind Sector Deal target of delivering 40GW of offshore wind by 2030, including an ambition to deploy 1GW floating wind in the same timeframe. As a less-established technology, floating offshore wind will undoubtedly require further demonstration projects to drive down costs, pushing its deployment at scale further into the future.

- Build Back Greener, HM Government's Net Zero Strategy for the UK [30] reiterates the keystone policies included in other publications and commits to take actions so that by 2035, all our electricity will come from low carbon sources, including offshore wind (importantly aligning with the Sector Deal), onshore wind and solar. The strategy recognises the need to deploy existing low carbon generation technologies at close to their maximum potential to reach the sixth Carbon Budget, as well as improving the cost efficiency of offshore transmission networks and cable routes. The strategy describes an approach for the 2020s of taking “no or low regrets” actions, which are defined as those that are cost-effective now and will continue to prove beneficial in future. They include actions taken to reduce demand and avoid locking in to high-carbon solutions, instead pursuing low carbon alternatives to drive deployment at scale. A framework for the categorisation of actions as “no or low regrets” is included at Section 3.6.

- The step change in low carbon infrastructure development required to meet Net Zero has resulted in the publication of revised draft National Policy Statements (NPS) [31, 32] to support planning decisions in England and Wales. Draft NPS EN-1 sets out the Government’s policy for delivery of major energy infrastructure, and EN-3 covers both onshore and offshore renewable electricity generation. Given the increasing urgency of action required to combat climate change, the draft NPSs are recognised as being “transformational in enabling England and Wales to transition to a low carbon economy and thus help to realise UK climate change commitments sooner than continuation under the current planning system.” The fundamental need for the large-scale infrastructure which draft NPS EN-1 considers remains the legal commitment to decarbonisation to Net Zero by 2050 in order to hold the increase in global average temperature due to climate change, to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels. In noting the crucial national benefits of increased system robustness through new electricity network infrastructure projects, draft NPS EN-1 also recognises the particular strategic importance this decade of the role of offshore wind in the UK’s generation mix. Offshore wind “presents the challenge of connecting a large volume of generation located beyond the periphery of the existing transmission network” and therefore sets an “an expectation that there will be a need for substantially more installed offshore capacity … to achieve Net Zero by 2050.”

- In April 2022, the UK government published an urgent British Energy Security Strategy (BESS) [108]. While the BESS is not strictly a policy in support of Net Zero, the measures it seeks to encourage do support Net Zero and increase the case for need for the Project. Key points from the BESS are therefore introduced at this point in this Statement of Need.

- The BESS is relevant to the case for need for the Project because it explains the important energy security and affordability benefits associated with developing electricity supplies which are not dependent on volatile international markets and are located within the UK’s national boundaries. The urgency for an electricity system which is self-reliant and not reliant on fossil fuels is enormous in order to protect consumers from high and volatile energy prices, and to reduce opportunities for destructive geopolitical intrusion into national electricity supplies and economics.

- The BESS raises the UK’s ambitious target of 40GW of offshore wind operational by 2030, by 25% to 50GW, up from 13.6GW in July 2022 [107]. Section 9 following provides an overview of the current The Crown Estate (TCE) Project Listings [10], which show that delivery of 53% of the current forward offshore wind pipeline, at the currently proposed capacities, would be required in order to meet the BESS aims.

- The clear UK Government policy established in the BESS is being delivered in part via the Energy Security Bill, which was introduced to the UK Parliament on 6th July 2022 and as at October 2022 is progressing through Parliamentary process.

- With increasingly interconnected markets – in electricity as well as source fuels such as coal oil and gas – market shocks can be felt through neighbouring international markets and more broadly. Oil and coal, historically international markets, drive global prices through supply chains which connect source and need and the many markets and exchanges which allow swaps and trades to be transacted across the world. Although gas has historically been supplied through pipeline (i.e. fixed) infrastructure, Liquefied Natural Gas has become increasingly prominent in connecting gas supplies with markets. Gas is now much more of a global market than once it was.

- In 2021, BEIS unveiled plans to decarbonise UK power system by 2035 by building a secure, home-grown energy sector that reduces reliance on fossil fuels and exposure to volatile global wholesale energy prices [91].

- The first quarter of 2022 demonstrated how the UK is exposed to volatile energy prices through international energy markets in gas, oil (and its derivatives) and coal. Energy commodity price rises in 2022 have and will continue to filter through to consumer electricity bills. While the UK once was energy independent, it now is dependent on imports of (in particular) oil and gas. The UK’s dependency on imports increases its exposure to volatile international prices, particularly when either demand is high in other markets (e.g. a deep cold period in South East Asia in late 2020) or supply is risked through the weaponization of energy supplies, as has been the case since early 2022.

- In the BESS, the Prime Minister at the time wrote: “If we’re going to get prices down and keep them there for the long term, we need a flow of energy that is affordable, clean and above all, secure. We need a power supply that’s made in Britain, for Britain.” [108, p3]

- The BESS sets out the immediate need to manage the financial implications of soaring commodity prices in the near term, on households and businesses which are already feeling economic pain as the post-Covid cost of living has risen: “The first step is to improve energy efficiency, reducing the amount of energy that households and businesses need." [108, p5].

- However the strategy also sets out the long-term goal of “address[ing] our underlying vulnerability to international oil and gas prices by reducing our dependence on imported oil and gas." [108, p6].

- The BESS aims to:

- Increase the pace of deployment of Offshore Wind by 25%, to deliver up to 50GW by 2030, including up to 5GW of innovative floating wind. Wind will contribute over half the UK’s renewable generation capacity by 2030. [108, p16];

- Consider all options, including Onshore Wind, through the improvement of national electricity network infrastructure and support of a number of new English projects with strong local backing, so prioritising “putting local communities in control" of local onshore solutions. Repowering of existing onshore wind sites is also under consideration. [108, p18];

- Support a 5-fold increase in deployment of solar technology by 2035, recognising the abundant source of solar energy in the UK and an 85% reduction in cost over the last ten years, of solar power;

- Increase UK plans for deployment of civil nuclear to up to 24GW by 2050 – three times more than operational capacity in 2022, and representing up to 25% of our projected electricity demand. This includes the intention to take one project (Sizewell C) to Financial Investment Decision (FID) during the current Parliament, and two projects to FID in the next Parliament, including Small Modular Reactors, subject to value for money and relevant approvals. [108, p21]. The selection process for further UK projects is anticipated to be initiated in 2023 [108, p22]; and

- Double the UK ambition for hydrogen production to up to 10GW by 2030, with at least half of this from electrolytic hydrogen [108, p22], facilitated by bringing forwards up to 1GW of electrolytic hydrogen into construction or operational status by 2025.

- Section 4.5 of this Statement of Need describes the electrification of GB homes as a key driver of future electricity demand. The BESS pursues this aim with increased vigour: electrification is a key measure not only for decarbonisation but also for energy security and affordability reasons. In the near-term, the BESS sets out a high-level action plan to upgrade the energy efficiency of at least 700,000 homes in the UK by 2025, and to ensure that by 2050 all UK buildings will be energy efficient with low-carbon heating. Further, the BESS sets out an intent to phase out the sale of new and replacement gas boilers by 2035, thereby furthering the electrification of heat in homes. [108, p12].

- The BESS also notes the improved cost competitiveness of electrically powered heat pumps which can displace natural gas from use in homes and buildings. Government is targeting 600,000 heat pump installations per year by 2028 and aims to expand heat networks and designated heat network zones to further the electrification of home and commercial heating. A “Rebalancing" of the costs placed on energy bills away from electricity is also intended to incentivise electrification across the economy and accelerate consumers and industry's shift away from volatile global commodity markets over the 2020s. [108, p12].

- Supporting the rollout of electric vehicles as part of Government’s electric vehicle infrastructure strategy, will also increase demand for electricity in future years, from potentially as early as 2023.

- The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders reported a 100% increase in Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV) sales in the UK in the year-to-date (end March-22) versus the same period last year, and over 16% of all new vehicle purchases in the UK in March-22 were BEV. Ongoing grants (available until at least March-23) and cheaper running costs are anticipated to continue to push EV market share over the coming years. [109].

- Government is also facilitating the adoption of electricity into transport through its Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Strategy (March 22) which sets out the expectation, by 2030, of there being around 300,000 public chargepoints as a minimum in the UK [up from just 30,000 in the first quarter of 2022], but there potentially being more than double that number, delivering “Effortless on and off-street charging for private and commercial drivers" [110, pp4&5].

- The rollout of a significantly higher capacity of renewable generation is therefore required to meet decarbonisation as well as energy security aims and the urgency for delivery as increased.

- Carbon Capture Usage and Storage (CCUS) retains its important potential role in a decarbonised economy. Government aims to deliver on their £1 billion commitment to four CCUS clusters by 2030, with the first two sites selected in the North East and North West currently proceeding through Track 1, with the Scottish Cluster in reserve. [108, p15].

- CCUS retains its important place within the BESS although it has not attracted a more prominent role relating to energy security than that with which it has already been tasked in the Energy White Paper and the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan, This is because CCUS is an enabler of eliminating carbon emissions from fossil fuel use, rather than providing a power source which does not require fossil fuels as an input energy source.

- Nuclear is poised for its third UK renaissance, but would only deliver its first megawatthours from the middle of the 2030s – and due to prevalent Scottish policy – not in Scotland. The UK’s nuclear renaissance of the 2000s resulted in the construction (currently ongoing) of just one nuclear power station, Hinkley Point C, which would currently not be completed until June 2027 with the possibility of a further 15-month delay to September 2028 [111].

- Although the BESS includes an aim to achieve a FID at one more nuclear power station by the end of the current parliament, it is important to recognise the significant political, financial and delivery risk associated with nuclear development. There is a long road ahead before any clean energy generated from nuclear technologies can be “banked" in the fight against climate change.

- The BESS recognises the critical role of renewables in accelerating the transition away from fossil fuels, and notes that renewable capacity in the UK is currently set to increase by a further 15% by the end of 2023. However further and faster actions are required to increase our national energy security and reduce our dependency on fossil fuels, and the exposure consumers currently have to their volatile prices.

- Accelerating the domestic supply of clean and affordable electricity also requires accelerating the connecting network infrastructure to support it, and the BESS also includes measures designed to increase the pace of improvements and enhancements to the NETS to enable the connection of the required level of renewable generation capacity both within the 2030 timeframe and beyond.

- Work has already commenced in this regard with the formation of a Future System Operator (a national organisation taking over the role of Electricity System Operator, currently carried out by National Grid) and programs of action such as the annual Network Options Assessment (NOA) and (ongoing at the time of writing) Holistic Network Design (HND), part of the Offshore Transmission Network Review, which aims to develop a strategy to coordinate interconnectors and offshore networks for wind farms and their connections to the onshore network and bring forward any legislation necessary to enable coordination. See also Section 9 below.

- The path to national control of nationally generated electricity and reduction of exposure to the volatile prices associated with international supplies of fossil fuels, and the path to a low-carbon energy system of the future, which minimises potentially catastrophic changes to the global climate, are the same path.

- The BESS provides an increase to the requirements for both the scale and the urgency of delivery of new low carbon generation capacity, by refocussing the requirement for low-carbon power for reasons of national security of supply and affordability, as well as for decarbonisation.

- The increase in ambition for hydrogen generation as set out in the BESS further supports the development of greater capacities of renewable generation and with greater urgency.

- Consenting the Development will be an essential boost to meeting the urgent need for low-carbon sources of electricity in the UK to meet growing electricity demand and the BESS ambitions for electrolytic hydrogen production by 2030.

3.6. Low and no regrets options

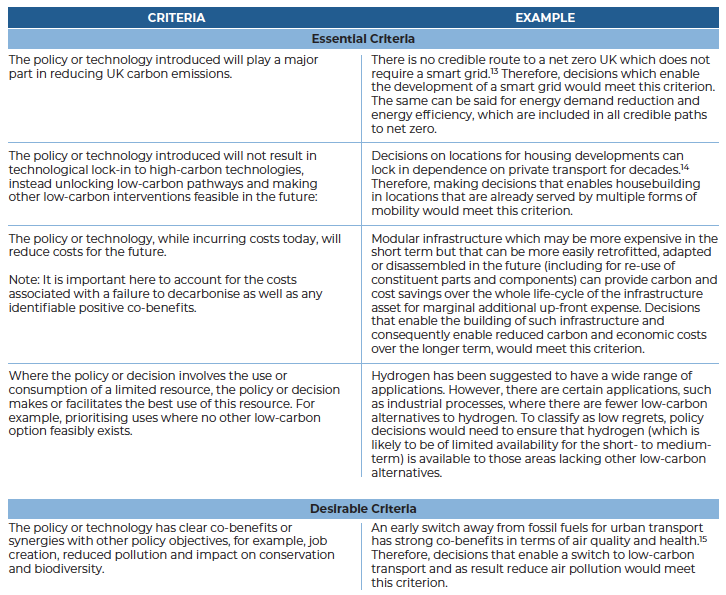

- Both the Scottish Energy Strategy [23] and the Net Zero Strategy for the UK [30] introduce the concept of “low and no regrets” options and actions. In 2021, the National Engineering Policy Centre (NEPC) authored and published a framework for rapid low regrets decision making for net zero policy [33]. The framework includes a definition for low regrets decisions as “urgent decisions that must and can be made now to have a significant impact on decarbonisation”. Such decisions would be expected to unlock pathways towards net zero, provide options and flexibility and not close off options. NEPC's framework includes four essential criteria and one desirable criteria for low regrets decisions, included at Table 3‑1. Although the framework is designed to be applicable across the UK, it is here proposed that it is applicable also to Scottish decisions for Scotland, and therefore provides support in favour of the case for consent of the Project.

Table 3‑1: Framework for low regrets decisions

[33]

- This Statement of Need makes the case that consenting the Project is a no or low regrets decision for Scotland for the following reasons:

- Section 6.2, Section 6.3 and Section 6.5 illustrate that offshore wind will play a major part in reducing Scottish carbon emissions, and the Project is an essential element of the future Scottish offshore wind project pipeline;

- Section 5.5 illustrates that rather than locking in high carbon technology, the Project helps lead away from high carbon technology, for example, Section 4.7 describes the important role of offshore wind generation in the production of green hydrogen in Scotland. Further, Section 8.4 describes the beneficial effect a large fixed-bottom offshore wind fleet is expected to have on rapidly reducing the costs anticipated for floating offshore wind projects, therefore increasing the pace with which this nascent technology may come to market at scale;

- The Project, as well as supporting future cost reductions in floating offshore wind, will reduce the future cost of electricity to consumers. Section 8.2 describes how deploying higher capacities of offshore wind will displace more expensive generation technologies from the grid and therefore reduce the marginal price of power in Great Britain;

- The Scottish Offshore Wind Policy Statement sets out Scotland's near-term ambitions for the sector, and the Scottish Offshore Wind Green Hydrogen Opportunity Assessment articulates the important role offshore wind is expected to play in Scotland over the longer term. Seabed generally is in abundance in Scotland, however there are no seabed areas other than the proposed location of the Proposed Development which are of the required size and characteristics to host 4.1GW of low carbon offshore wind generation. The proposed seabed area should therefore be used for the important purpose of generating significant quantities of low carbon power. Section 3.7 and Section 7.9 describe that, if consented, the Project would become operational earlier than any other available options; that no other available options have been demonstrated to attract less environmental harm than the Proposed Development, and the Proposed Development is likely to be completed for a lower cost than other options of the same capacity, due to the water depth and seabed structures at the location, its proximity to viable grid connection points, and achievable scale.

- The Project has clear co-benefits in that the power it would generate would increase indigenous Scottish low carbon electricity sources, for use in the substitution of fossil fuels from use in the heat and transport sectors as described in Section 4.

3.7. The ScotWind leasing round

- The primary purpose of ScotWind Leasing is to grant property rights for seabed in Scottish waters for new commercial scale offshore wind project development. Marine Scotland, part of Scottish Government and the planning authority for Scotland’s seas and custodian of the National Marine Plan, leads in the identification of potential areas suitable for commercial scale offshore wind development.

- The first cycle of ScotWind Leasing - the first in a decade - opened for registration in 2020. Up to 8,600 square kilometres of Scottish seabed was available across multiple Plan Option Areas, with the expectation that ultimately, in total up to 10GW of offshore wind capacity would be developed within them [34]. Scotland's Sectoral Marine Plan for Offshore Wind Energy [25] noted that limiting the scale of development under the Plan to 10GW was required to reduce or offset the potential environmental effects of development. The Option Period associated with each lease is 10 years, after which time a lease cannot be requested so a project cannot be constructed.

- The first leasing round concluded in January 2022 with the award of 17 leases covering 7,343 square kilometres and a maximum potential capacity estimate of 24.8GW.

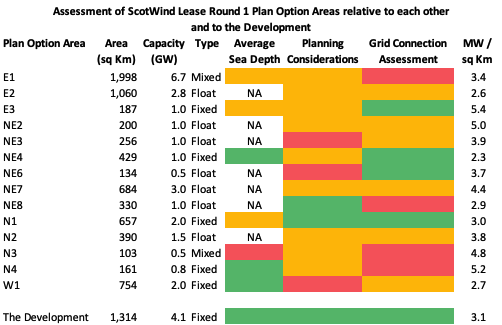

- For comparison, the Proposed Development is proposed to install 4.1GW of offshore wind over a total area of 1,314 square kilometres of varied seafloor morphology with sea depths ranging from 32.8m to 68.5m (measured against Lowest Astronomical Tide). The average sea depth across the Proposed Development Array Area is 51m.

- By awarding leases for significantly greater generation capacity development than the 10GW limit established in the Sectoral Marine Plan, CES has increased its ambition for the delivery of new offshore wind projects but also has allowed for attrition rates which will be likely due to the nature of the leasing and development processes. Scottish Renewables recommended a 30% MW attrition rate in their 2018 “An industry view of the Draft Sectoral Marine Plan for Offshore Wind” in order to reflect the more challenging conditions in Scottish offshore waters relative to the rest of the UK, particularly regarding water depth, ground conditions and grid charges.

Figure 3‑5: ScotWind Lease Round 1 Plan Option Areas and Scotland's onshore transmission network

Adapted from [35, 36, https://www.offshorewindscotland.org.uk/scottish-offshore-wind-market/]

- ScotWind Leases have been awarded to 9.8GW of fixed bottom offshore wind, 14.6GW of floating offshore wind (FOW), and 0.5GW in a Plan Option Area with mixed technology. Although the Plan Option Areas with fixed bottom technology are generally located closer to shore than those with floating technology, 6.4GW of fixed bottom wind is proposed in areas with average sea depth greater than 60m, a depth which is technically achievable for fixed bottom wind, but potentially with greater complexity and therefore associated cost and time, than installation in shallower seas. 3.4GW of fixed bottom offshore wind is proposed for Plan Option Areas with a depth comparable to that of the Proposed Development Array Area (<60m).

- The total Development Plan Option area identified in the Sectoral Marine Plan covered 12,810 square kilometres across 16 identified areas, with a maximum development scenario of 26GW, likely delivering in the early 2030s. The significant majority of successful projects marry up to entries on the TEC Register [16], leading to the conclusion that offers for sufficient grid connection capacity to accommodate wind capacity delivered under ScotWind Lease Round 1 have already been issued to and accepted by developers. The majority of grid connection dates are currently scheduled for 2033.

- Large (>100MW) generators generally require connection to higher voltage (>=275kV) circuits to be able to export their power in a safe secure and efficient manner. Figure 3‑5 shows an overlay of Scotland's onshore transmission network on the locations of the Plan Option areas, with 275kV circuits coloured red and 400kV circuits coloured blue. It is clear that some Plan Option Areas are less accessible to suitable grid connection points than others, and in the detailed studies to follow a further level of attrition may occur. In any event, longer grid connections tend to be more expensive and the reliability of High Voltage DC (HVDC) cables decreases with their length. Section 7.8 also provides an overview of the outcomes of National Grid’s Holistic Network Design the challenges associated with connecting generation above National Grid boundaries in Scotland, related to grid constraints and the grid strengthening required to enable larger power flows from north to south in future years.

- A comparison of the number of different planning considerations highlighted as potentially significant in Scotland's Sectoral Marine Plan for Offshore Wind Energy identifies that some Plan Option Areas require detailed study and analysis to understand and mitigate potential harm arising from development, a process which in at least some cases may take many years.

- Potentially significant planning considerations include visual amenity (both seascape and landscape impacts), shipping and navigation, MoD impacts (including facilities and radar interactions), fish spawning and habitation as well as commercial fishing grounds, bird populations (including five areas to the north east which have been classified as being “subject to higher levels of ornithological constraint”, benthic seabed areas and in one instance, noise (due to proximity to human populations). Many of these considerations are common across multiple Plan Option Areas, and some are common also with factors which have been addressed in the process of preparing a planning application for the Proposed Development.

- A summary of this qualitative analysis is included at Table 3‑2.

- The following assessment criteria drive the colour coding in Table 3‑2.

- Average Sea Depth. Green: Mainly <60m. Amber: mainly 60 - 100m. Red: mainly >100m. FOW not graded.

- Planning Considerations. Green: <3 significant topics. Amber: 3 or 4 significant topics. Red: 5 or more significant topics. Gravity of significant topic not assessed.

- Grid Connection. Green: shortest distance from Plan Option Area to closest point of connection (POC) on existing 275kV or 400kV point of connection (POC) is comparable to the Project’s Branxton POC distance. Amber: shortest distance is greater than the Project’s Branxton POC distance. Red: shortest distance is significantly greater than the Development's POC distance. Actual cable route not considered.

Table 3‑2: Assessment of ScotWind Lease Round 1 Plan Option Areas relative to each other and to the Project

- Against this context, the results of the first leasing round broadly match the required maximum development scenario (24.8GW for leases offered vs. 26GW identified) but on a smaller leased Development Plan Option area (7,343 vs. 12,810 square kilometres) suggesting that a degree of attrition has already occurred in the selection of suitable seabed. However this has been partially offset by an increase in potential capacity installed per square kilometre. Indeed, the development scenarios were predicated on the installation of 2MW generation capacity per square kilometre, however the offered leases average 3.4MW generation capacity per square kilometre.

- The challenges of sea depth, grid connection and environmental impacts suggest that further attrition is possible in Lease Round 1 projects over the coming years – i.e. that not all of the issued leases (24.8GW) will be delivered.

- The environmental, technical and decarbonisation characteristics and impacts associated with the Proposed Development are well advanced in their understanding in relation to comparable assessments of the ScotWind Lease Plan Option Areas, and the Proposed Development therefore compares well in terms of the risk associated with its delivery (quantum and timing) against the possible future projects progressing under ScotWind Lease Round 1.

- Further, there is no project or collection of projects coming forward under ScotWind which will deliver a comparable capacity of offshore wind generation as the Project (4.1GW) with technical, environmental or commercial risk profiles which are sufficiently advantageous relative to those of the Project and which therefore could objectively justify not consenting the Project, given the early stage of detailed feasibility analysis of the ScotWind projects. Therefore the decision to consent the Development will not result in a lock-in to a technology which cannot today guarantee the same decarbonisation benefit for lower environmental or commercial cost as future identified options.

- Against this context, it is the opinion of the Author of this report, that consenting the Project should be regarded as a low regrets decision.

3.8. Conclusions on historical decarbonisation and current policies

- Progress in UK decarbonisation to date has been achieved by “off plan” means. Renewable generation has delivered more capacity and generated more carbon-free electricity than was foreseen to be required due to the planned development of other low carbon technologies. However nuclear and CCUS have not delivered as was foreseen in the early years of the 2010s.

- Significant growth has been realised in now proven renewable technologies (onshore & offshore wind, solar) and this has made up for the contributions which nuclear and CCUS were expected to make to decarbonisation.

- Current decarbonisation plans for the UK and for Scotland rely on the deployment of proven renewable technologies (with offshore wind at the forefront) as well as unproven technologies, including CCUS, hydrogen and (for the UK but not currently for Scotland) nuclear. (Also see Section 5.6 for an analysis of FOW potential in Scotland and the UK).

- Scottish and UK policy both recognise an increased urgency in the need for low carbon electricity generation capacity deployment. Action during the 2020s will be critical to meet the 2050 Net Zero target, and electrification is the primary strategy going forwards both to decarbonise the current electricity system and also to provide low carbon energy to decarbonise other sectors, including transport, heat and industry.

- Lower-risk, short-timescale, large-scale proven-technology generation projects will be well placed to support many aspects of the whole-system solutions required to meet decarbonisation targets.

- Scotland, itself an instrumental contributor to the UK NDC, has set its own legally binding target of achieving Net Zero by 2045, and of achieving a 75% reduction in emissions against a 1990/1995 baseline by 2030.

- The Scottish Energy Strategy (2017) [23] establishes targets for 2030 to supply the equivalent of 50% of the energy for Scotland’s heat, transport and electricity consumption from renewable sources; and to increase by 30% the productivity of energy use across the Scottish economy.

- The Scottish Offshore Wind Policy Statement [22] supports the development of between 8 and 11GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030.

- The UK has made international commitments to achieve Net Zero by 2050 and to achieve economy-wide reductions in GHG emissions of at least 68% versus reference year levels, by 2030.

- The Offshore Wind Sector Deal [27] is a critical policy instrument which will drive the deployment of low carbon offshore wind to a target of 40GW of operational offshore wind capacity by 2030, in order to support the UK's NDC commitments;

- Government’s ambition, as described in the BESS, is to increase further the deployment of low-carbon offshore wind to 50GW by 2030, in order to support both the UK’s NDC commitments and improve the UK’s energy security position [108].

- Scotland holds a position of international leadership on Climate Change. Scottish policies position offshore wind as a key area for economic and environmental growth, and the Scottish government has committed to work with the UK government on climate change actions to support the UK’s wider policy and legal commitments, including meeting the Offshore Wind Sector Deal & 2030 NDC commitments.

- The 2030 targets are commitments in law. They do not in themselves assure that Net Zero will be delivered, but are critical stepping stones on the way to achieving Net Zero over committed timeframes. Governments and industry must strive hard to meet the 2030 targets in order to continue succeeding against the global climate emergency. However governments and industry must also look beyond the 2030 targets to determine what actions can be taken today which will de-risk further progress along the path to Net Zero. Not least because there is a duty on the UK government to ensure that the 2050 targets are met. Low carbon solutions must be delivered urgently now, and post 2030, and both the 2020s and 2030s are critical decades during which progress must be made.

- Whether a development is critical or not in order to achieve Scottish or UK 2030 targets is one element of the justification for its need. A further, equally important justification is the contribution a development will make to future decarbonisation, and the de-risking of future actions which have an identified need but whose delivery is not yet sufficiently assured. Scotland and the UK cannot afford to miss their respective 2030 targets, but they also cannot afford to miss the more demanding targets which are sure to follow after.

- The need for a development should therefore be assessed both in terms of its contribution to Scotland and the UK’s 2030 targets but also its critical contribution to the longer-term climate change Net Zero commitments for Scotland by 2045 and for the UK by 2050.